Give It Time

John Haberin New York City

Agnes Martin and Carmen Herrera

One can get to know Agnes Martin from almost the very start of her Guggenheim retrospective, but it takes a moment. The High Gallery, just off the ramp as one ascends, introduces her not with the breadth of her career, but with a single series. It also introduces her as a producer of light.

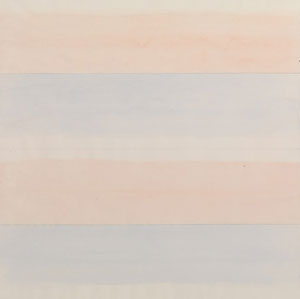

The room gives space to all twelve of her Islands, from 1979, and they appear all at once as twelve fields of white. They might have sucked in the light from that literally high gallery or the rotunda—and then thrown it back, but with a still greater intensity. Soon enough, though, one can see them all as broad horizontal stripes, separated by far thinner ones. They take on primary colors, each with its own glow.  The colors differ from canvas to canvas, although one might be hard pressed to pin them down. It hardly matters, so long as one takes the time to try.

The colors differ from canvas to canvas, although one might be hard pressed to pin them down. It hardly matters, so long as one takes the time to try.

Women in art have long taken time—time to find recognition and time to find themselves. Consider, too, another abstract artist with quite a history. Carmen Herrera appeared in the Whitney's inaugural exhibition in the Meatpacking District, "America Is Hard to See." She also lived to see her Whitney retrospective at age one hundred and one. Do not feel too bad, though, if you failed to recognize her—or missed her entirely. Herrera really has been hard to see. First, though, the Guggenheim and Agnes Martin.

Moving to the grid

Give it space. Give it time. That urgency and that measured pace underlie everything by Martin (and this is not about calls for "slow art"). Like all her mature work, too, they consist of pencil on oil or acrylic, but the retrospective also starts with a denial of just that, in a quote from the artist. "My paintings have neither object nor space nor line nor anything—no forms. They are about . . . formlessness, breaking down forms."

No doubt, but then it is up to the viewer to put them back them together. It took Agnes Martin a long time, so why not you or me? The quote also testifies to an uneasy relationship with late Modernism. And the curators, Tiffany Bell and the Guggenheim's Tracey Bashkoff, see Martin as a bridge between Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism, much like Walter Darby Bannard. One could well go further and see her as a bridge from early American Modernism to the rebirth of painting today. She died in 2004, at age ninety-two.

Like Herrera, she started slowly at that—and not only because of the obstacles that she faced a woman in abstract art and, likely as not, a gay artist. Born in western Canada in 1912, she spent much of her first forty years on the move. Her father died early, her mother took the family to Vancouver, her sister's pregnancy brought her to the United States in 1931, and she studied at Teachers College of Columbia University as both an undergraduate and a graduate student, but even then ten years apart. She also struggled with schizophrenia. Maybe that explains her need for happiness and stability in her art. Maybe it explains, too, her need for painting to appear as a vision.

Martin moved to Taos in 1954, when the show begins. She moved again to New York in 1957 at the urging of Betty Parsons, the dealer, and eventually back to New Mexico. And every one of her breakthroughs begins with shift in medium and in place. The show's first painting, Midwinter, abstracts away from nature, with white on irregular fields of black and gray. It recalls America's first abstract painter, Arthur Dove, as well as New Mexico's most famous admirer of the desert, Georgia O'Keeffe. She will take many of her titles from nature, like Islands, but she will always insist that her work is abstract.

For such a loner, Martin took well to others, at least in New York. She settled into Coenties Slip by today's South Street Seaport (where James Rosenquist would later take over her studio), in the same building as Robert Indiana and Ellsworth Kelly, another exponent of Minimalism and light. Neighbors included Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, which may be why she briefly scavenged wood for painted sculpture. She met Lenore Tawney, another woman artist driven by parallel lines—in Tawney's case with thread. She exhibited with Parsons and, before she left town, at the Guggenheim. She became closer still to Mark Rothko and Ad Reinhardt.

Her first paintings in New York introduce more regular geometry, such as stacked rectangles in shades of black, white, and gray. She could be regularizing Rothko and herself. Those later Islands reveal their colors slowly, like Reinhardt's black squares, but in white. She could be the anti-Reinhardt, with her slow pursuit of happiness in place of his acerbic wit. Later still, she even has a series of "black paintings," from 1989, a lost ancestor for black painting today. They defy him anyway, with some of her most legible stripes.

Vision and form

Grids appear at last in 1960, with a shift to drawing. They expand on canvas to six feet on a side, a format that Martin will keep. They already dissolve before one's eyes, and they have bare or painted borders so that the grid floats, like rectangles for Rothko. Yet they are also her most static work. At first she makes a point of filling each cell with a dab of paint. Soon after she covers the whole in dark paint or gold leaf, as if to pin the grid down.

She left New York abruptly in 1967, grabbed a pick-up truck, and crossed the continent for more than a year, with no firm destination. She had lost the support of Reinhardt, who died that year. She may have feared losing her studio—or feared her growing success. She may have had too much of the city for a wanderer and needed again to see the sky. Maybe her illness had caught up with her. Maybe, too, the heavy grids felt like a dead end.

Back in New Mexico, the darkness falls away. Martin experiments with watercolor, on her way to her signature pencil and ground. She alternates between horizontal and vertical stripes, in gray washes, with the illusion of still more colors to come, and (yes) those pale colors. The gaps between broader stripes bring them closer still to solid objects, like stripes for Frank Stella or Sean Scully. Yet Stella had moved on, and Scully had not yet come into his own. One should never forget her age, meaning both her early start and her persistence.

She retires to a nursing home in 1980, but still with a studio—obliged by age only to reduce her dimensions to five feet on a side. At the very end, in the new millennium, she gives geometry a greater prominence once again. First come more prominent colors for horizontals at dead center, like pulling apart the shutters to let in the light. She calls a painting Gratitude. Last come buoyant squares, a row of triangles, and a trapezoid, all in black. She could be looking past her death, but she calls the trapezoid her Homage to Life.

Martin always has that tension between vision and form. Put it down to her abiding interest in eastern religion, which she never practiced, or to her perhaps closeted sexuality, which she did little to claim. "My response to nature is really a response to beauty," she insists. "It is beauty that really calls." In turn, the insistent grid of her abstractions is not an end in itself, but "represented innocence." Maybe, but she may never have had time for innocence herself, except in paint.

Martin uses the extremes of paper and large canvas to push one back and to draw one in. The Guggenheim loses much of the second, with the tilted floors of its bays. One cannot get close, however hard one tries. One has to settle for a place apart to look. Give it space. Give it time.

Not so hard to see

At its opening of "America Is Hard to See," the Whitney had only recently acquired its work by Carmen Herrera, from an artist who had not had exhibited here in almost twenty years. Born in Cuba in 1915, eleven years before Zilia Sánchez, she spent her formative years in Paris, and she was, of course, a woman. She stuck with plain geometry even as all eyes turned to Abstract Expressionism and gesture. Now, in turn, she can be deceptively easy to see.  Her work looks so familiar, from the spare, nuanced, off-kilter color fields of Ellsworth Kelly and Lynn Umlauf—or the clear patterns, rigorous logic, and insistence on canvas as a material object of Frank Stella. The surprise comes in finding her name on the wall label, along with her dates.

Her work looks so familiar, from the spare, nuanced, off-kilter color fields of Ellsworth Kelly and Lynn Umlauf—or the clear patterns, rigorous logic, and insistence on canvas as a material object of Frank Stella. The surprise comes in finding her name on the wall label, along with her dates.

Now the Whitney means to change all that, with "Lines of Sight." It focuses on just twenty-five works from just thirty years, from 1948 to 1978. Together with a recent survey in Chelsea, the Met's "Epic Abstraction," and the Whitney's own survey of color in the 1960s, it makes Herrera both more historical and more contemporary. It begins with her move with her American husband to Paris, after nine years in New York—not so very far, it turns out, from the Whitney's first home on Eighth Street. And it centers on nine of the fifteen surviving works in Blanco y Verde, spanning twelve years, including the painting in the Whitney. Beginning in 1959, several years after Herrera's return to New York, the series goes far to define her maturity.

Stella would have understood the title ("White and Green") as a signal that "what you see is what you get." He would have admired her narrow triangles, not so far from his stripes and similarly playing off a painting's edges and center. He would have insisted on looking to the sides of the canvas, where the paint continues. He would, that is, if he had ever seen them before undertaking his own. Meanwhile Kelly would have appreciated the broad areas of color, sometimes filling an entire canvas set against another, much like his. He would have liked the arbitrary choice of green and its varied, intuitive placement.

Herrera is capable of Stella's drive and Kelly's serenity, without the latter's frequent dryness and the former's frequent fuss or chill, while making even Virginia Jaramillo by comparison a youngster. She gets there, though, not by repetition on the one hand or refusal of symmetry on the other—but rather by displacing shapes, so that they form new ones. Sometimes staggered triangles leave a square at the center, and sometimes staggered rectangles seem to eat into one another like forks. In the Whitney's painting, two panels lie above one another, both white except for a slim green triangle running along the lower edge of the top panel. It could be minding the gap, as they say in London, which one might otherwise overlook. It could also be pointing up from the gap and extending it, as if prying the painting apart.

A room to the left shows her before 1958, with a busier Modernism out of Fernand Léger or Futurism. Circles lie within triangles or vice versa—or rectangles within ovals within rectangles, like a head by Alexej von Jawlensky. As Herrera streamlines her vocabulary, she lands in a diamond of alternating black and white stripes, nearly a decade before Stella's black paintings or those of Jake Berthot andChristopher Stout. A room to the right shows her settling down after 1970 and brightening her colors. She also tries her hand at estructuras, or stand-alone structures in painted wood, just as Stella's later work came off the wall. Yet here, two, adjacent parts seem slightly ajar, as if opening under their own power.

The show's climax comes even before one enters. The curator, Dana Miller, spreads a series of seven paintings, for the days of the week, across two front walls. They shifting arrangements have a new and more persistent energy. They also suggest a stronger connection to the return of painting today. Painters like David Rhodes, Gary Petersen, Don Voisine, and so many more could not have taken Herrera for a model for their tapering geometries either, no more than Kelly and Stella, but they would know where to look. Who said America is hard to see?

Agnes Martin ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through January 11, 2017, Carmen Herrera at The Whitney Museum of American Art through January 9 and at Lisson through June 11, 2016. I last visited Agnes Martin in 2011.