They, the People

John Haberin New York City

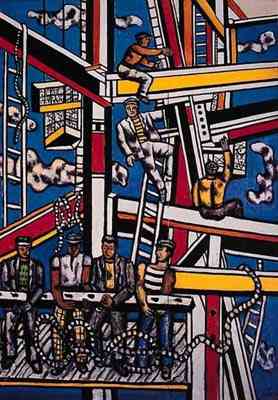

Fernand Léger

I take Léger seriously—or at least his name. It means light in French, like a hot-air balloon, and I had always figured Fernand Léger for a lightweight. Those simple cylinders and spheres—and even simpler people—they looked to me as hollow and mechanical as the Tin Man on his road to Oz.

They rise far so quickly into the air. There they go, up, up, and away, as if all too ready to abandon Cubism's penetration into this world.

I had better think again. From the moment I walked into Léger's modest retrospective at New York's Museum of Modern Art, I knew that I had it backward. His glory and his weakness are the inordinate demand for weight. Over the course of his life, that glory may have left Léger with people empty even of air—but never of ambition.

Lightweight

At some point, Léger's dream of humanity became a bad word. I do not mean at meetings of Earth First!. I mean in postmodern art.

Humanism became too tied up with the fight against Communism or capitalism. Worse, it got hard to remember which. Meanwhile the individual—the white American kind, at least—was out shopping. The human tradition passed from a grand European time line to an even longer line for the remodeled Louvre.

Of course, the cause of humanity in art will not die so easily, not as long as artists and the public still look up to the Renaissance. Conversely, artists started to question it well before the 1960s. Even before Picasso painted Guernica and Anthony Blunt praised it to the skies while spying for Stalin, artists were arguing over who represents the people. I think especially of Léger.

A Cubist who found Communism and lost it again in America, Fernand Léger makes a short history of Modernism all by himself. But was he always aware of its tensions? By concentrating on just sixty paintings, plus a handful of related drawings, the Modern offers a special chance to question the depth of Léger's ambition. At the same time, it gives that ambition the space it deserves.

The most massive of his shocks—and my favorite work on display—confronts one right as one enters. A big painting covers the partition that serves as the exhibition doorway. Its deep browns and greens, shot through with patches of stranger, still-brighter colors, evoke this earth. I could imagine both a landscape and the smoky streets of Paris. I could see hints of the scary cliffs and scarred trees of his native Normandy. I could feel the constant vitality of the capital city that Léger made his own.

In 1911, just turning 30, Léger found a new style, as a key player in inventing abstraction. Dense forms tumble forward, quite out of the picture plane. By taking Cubist spaces to a large, active scale, Léger in one shot practically skipped forty years ahead, to Abstract Expressionism. Or did he? The difference may suggest the forced vision of humanity in his art.

Universals

Abstract Expressionism means something less eager to impress. One enters for oneself the space between Pollock's drips, Arshile Gorky and his Surrealist nightmares in painting and drawing, and de Kooning's rapid witticisms. Léger wants no room to get lost in painting. His art stands grandly above the museum-goer, with no time to waste on spontaneity and triviality. He has monumentalized Cubism.

Léger aimed for art as important as it darn well should be. Picasso's clever philosophical puzzles, Braque's delicate materialism, and Gris's acid, late-night scenes—all of them must have seemed small potatoes in Léger's urban bistro. How esoteric, both fine art and the café society it describes, when humankind is entering the twentieth century. Like Pierre-Auguste Renoir late in life, Léger sought painting more relevant and lasting than mere impressions. Increasingly he ended up with Renoir's pat conclusions as well.

Léger looked for art's universal language. Within three years of those first paintings, he came up with his trademark spheres and cylinders, like Chardin's still life gone mad. With that device, he could define a canvas in two and three dimensions. At first, still much as in Cubism, these and these alone fill the space. Although the graininess will later smooth out, the shapes are deservedly the mark of textbook Légers.

With them he created his color scheme of primaries broken by intense greens and purples, each to a separate object. With them, too, he adopts his characteristic symmetrical compositions and frontal lighting. They also allow some neat bits of bare canvas, but more for painterly care than for artistic freedom. His name may mean light, but not in the sense of luminous, and even his skies quickly become airless. The sharp white highlights and gradations of gray remind me of computer-generated shadows.

Within ten years he had his subject matter, working-class men and women. They sit idly. They go to the beach and to work. They may tumble and weave, but most often they face front and glower, much like those cylinders.

More and more he preferred women as subjects, maybe because breasts reminded him of his spheres. Like Duchamp with a machine, he took people for ready-mades. He liked household appliances, too, before Stuart Davis in America, but he forbade Cubist wordplay far too much to anticipate Robert Rauschenberg and in his name-brand images. Like Robert Delaunay before him, he built skyscrapers, but they never reach to the skies because they never risk crumbling to the earth.

Mass markets

Léger loved humanity, enough to have served in World War I only to suffer nightmares from combat, but he stayed oblivious to human feelings. His sad-eyed musicians might stand for France in 1944, under Fascism, just as George Segal's plaster casts try to stand for everyman in the industrial age. But then again maybe not, and that same year his families were back at the beach. Their faces look joylessly determined, but never alienated.

For Léger the dream of humanity tugged just a little too too hard. For plenty of other artists as well, it never stopped tugging, and what would art be without its dreams? "We can afford to ask," said Thomas Hart Benton in America, "whether a tablecloth and an apple, in terms of human value, are worth all the effort." One of his pupils, Jackson Pollock, went on to become a hero of the anti-Stalinist left. No wonder Léger's images keep their hold on memories of modern art.

But that version of Modernism is easy to tell. So is its converse, the struggle of art, even for Suprematism and other art under Stalin, to see with the inner eye of creative freedom. From both perspectives, of the masses and the individual, critics have seen modern art as the dream of human value. That is why it needed a good shaking up, too, assuming that Postmodernism is up to the job.

There is another history of Modernism, however, waiting to be told. It is about a tension between those two notions of humanity within a single work of art.

One can ask not just whether Picasso's portraiture—or Les Demoiselles d'Avignon—exploited women and African images, and so they did. However, one can also ask how the appropriation entered into his art. One can ask what happens when Pollock blew up Surrealism and Cubism to the scale of public art. If the people is a lie, one can ask how artists take damaging lies seriously enough to make them delicate, necessary fictions.

I do not believe everything I read, however, and not every artist lies convincingly enough to make the lie interesting. Léger juggled ordinary people with the humanity they represent. In his first Cubist works, that enabled him to find both. As he examined these ideals less and less, I think he increasingly found neither.

All work and no play

I long to draw a deeper meaning from what Léger represses, from working-class suffering to the desire behind those perfectly rounded breasts. I like his repressing people in order to praise them, because I keep hoping for that tension to animate his art.

I want his obsession actually to grow, to become as perfect and unsettling as Mondrian's. Like Mondrian's persistent variations on a theme, I hope for serious play—even for art as foreplay. Léger, however, had a framework that excluded play. That way, art could be almost as important as the play of others.

The very first cylinders meant so much to Léger, I think, because they freed up his lifelong indifference to terms like representation and abstraction. Whereas Cubism had stuck to ordinary reality, Léger never worried about it. He preferred to distinguish the imaginary from the real, and he insisted that painting be real.

Postmodernists distrust both humanism and high Modernism. Léger made the implications of those ideas problematic long ago. Postmodernists even think they can encapsulate history, too. Barbara Kruger does it all the time, in a sentence. I take maybe 1,500 words. Léger might have liked that, so long as it is real enough.

How successfully did Léger exclude the pathos of the imagination? Even after a well-composed, concentrated retrospective, I may never know. When he reached New York near the end of his life, in the midst of postwar construction, he must have thought that he had found the future. There, up on the beams of skyscrapers, balanced as easily as on a tricycle, his men continue to smile.

Fernand Léger ran at The Museum of Modern Art through May 12, 1998.