Geomancy

John Haberin New York City

Vija Celmins, Yto Barrada, and Bettina

At the dawn of the fifteenth century, a young Florentine was foraging in the ruins of ancient Rome. Filippo Brunelleschi had not yet introduced one-point perspective into Renaissance art or created the dome for Florence's cathedral on an unheard-of scale. He had not yet invented the very role of an architect as designer, planner, engineer, and manager all rolled into one.

He was still looking for clues in antiquity, but how? Was it architecture, archaeology, or geomancy, the art of scattering earth and divining the future in its patterns? The few pious souls who took note of him could not have approved, but he kept his mouth shut and his eyes close to the ground. Even now, Vija Celmins is doing much the same, and it can still seem like magic.  In paintings and drawings spanning more than fifty years, she attends to the smallest details of the ocean's surface, the night sky, a spider's web, and rocky expanses from the American West to the moon. They may look minimal or beautiful, but she is only trying "To Fix the Image in Memory"—while Yto Barrada and Bettina find Minimalism and nature on Governors Island.

In paintings and drawings spanning more than fifty years, she attends to the smallest details of the ocean's surface, the night sky, a spider's web, and rocky expanses from the American West to the moon. They may look minimal or beautiful, but she is only trying "To Fix the Image in Memory"—while Yto Barrada and Bettina find Minimalism and nature on Governors Island.

The illusion of illusion

You will hear it often at the Met Breuer: "that is so beautiful." Vija Celmins traffics in enigmatic surfaces close to abstraction—their darkness interrupted by the meticulous highlights of reflected moonlight, sunlight, spider silk, or stars. She is just as skilled with shades of gray for hazy skies or the open sea. You might not exactly want to enter spaces like these, assuming you could. Still, their very bleakness ties them to the Romantic sublime, the space of icy waters for Caspar David Friedrich or the perfect storm for J. M. W. Turner.

She is just as impressive as an illusionist. She seems to have counted every ripple and every pebble, and she indeed does fix the image in memory. The show takes its title, though, from a different work—and another challenge to the naked eye. She gathers small stippled stones and then adds an equal number of her own making, in painted bronze. I doubt that even she could tell you which is which. I doubt that she would want to.

Celmins takes care to build her illusions, with twenty or more layers of paint, sanding the surfaces in between, and she takes time out for a convincing if gigantic pencil and pink erasers in sculpture. She takes care for their subject as well. She could see the sea from her studio in Venice Beach, in California, where she moved soon after grad school at UCLA, and she loved side trips to the desert. A spider's web caught her eye one night in 1999, and she kept coming back for more. In practice, she works entirely from photographs, but then photography has long had a creepy authority. Besides, she had no other way to explore the moon. Sure enough, she had just started her earthly series in time for the lunar landing in 1969—the subject of "Apollo's Muse" recently at the Met.

Then again, is the illusion itself an illusion? If she let her pencil or her brush slip, would the ocean or a bronze rock look any less real or only different? Celmins imposed patterns from the very first, like a black cross that emerges from the waves, and some lunar rock formations are composites. Some sheets pair shots of the earth and space, just to let you know that they are all but indistinguishable. Others throw in an assemblage by Marcel Duchamp, with its own radial patterns of reflected light. Here the greatest illusion lies in shadows at the edge of the clippings, for the appearance of collage.

The sense of beauty may not stand up to scrutiny either. The retrospective takes two floors, roughly corresponding to her years in California and, after 1980, in New York. Yet just a single room can grow repetitive, and you may walk through faster than you would like—even with stops to express aloud your awe at her geomancy. You might think that an artist moving east in her early forties would experience a new beginning, but her themes have hardly changed. In the most overt shifts, they actually get a little duller. Celmins reduces the layers and reverses some night skies, leaving black dots here and there in plain white.

Nor are the challenges to illusion and beauty unintentional. In fact, they are what sustains the work. Celmins may seem ever the romantic, but she belongs to a time of Minimalism and Postmodernism. She depicts two dimensions as two dimensions, and she knows that the picture plane, like perilous waters or the moon with no air to breathe, is an obstacle. She knows that, in working from photographs, she adds a further distancing. She wants an image, she says, "that invites one in and keeps one out."

Smoke and mirrors

Brunelleschi kept his secrets, even from Donatello, the future great sculptor, whom he brought along for the ride to Rome. Celmins is open about what she is doing—not just in statements, but also by highlighting her processes. She likes how cracks in a vase or the desert floor parallel cracks in caked oil, and she is not above adding a few as a further illusion in paint. She likes how, when she turned to charcoal, it left something like earthly or lunar dust. Then, too, Brunelleschi was in self-imposed exile and a bit of a snit, after losing the commission for bronze doors to the Baptistery in Florence, a competition that spurred the Renaissance. Born in Latvia, Celmins is an exile, too, and it shows in the bleak beauty of her art.

The Russian army made her one as a child, and she lived in refugee camps before finding a home in Indiana. Some of her first paintings depict letters to and from her mother—the red, white, and blue edges of air mail clearly visible and each postage stamp a blurry painting in itself. For the moon, she draws not on America's one small step for a man, but on photos from the Russian space program, while her paintings of dive bombers look back to the U.S. Air Force in World War II. Apparently, she cannot think of even exile without mixed feelings. Still, almost everything in her work is a disaster in the making. In her early work, it has already occurred.

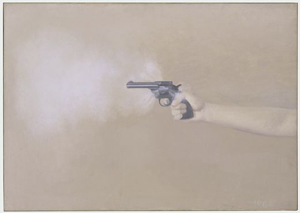

Her first paintings run to extended moments of impact. A handgun held tautly at arm's length and a monstrous locomotive release their cloud of smoke. A zeppelin is all but waiting to explode. Already, too, Celmins is keeping her distance. These are past technologies and long-past disasters. They are also gray paintings, with a smudgy brush that accentuates the smoke and mirrors—or the masses and the smoke. Like her more exact work later, this is not the photorealism you expected.

She may approach the infinite, but she begins up close, much like the eye's proximity to the surface of the ocean. She also begins in the confines of her Venice studio, with paintings of a space heater, a hot plate, and a fan. With another artist, you might feel the warmth or the chill. With Celmins, you are aware instead of absence—the absence of a proper radiator, a proper kitchen, or ventilation, not to mention the absence of the artist or her art. Again, she is close to the absence of life in the desert or on the moon. Is it mere coincidence that her first field trips were to Death Valley?

Those paintings of her studio are already close to black and white, apart from the glow of the space heater and hot plate. You may come to miss it. They are also about seeing and withholding. A desk lamp in her studio appeals to her because its twin lights remind her of eyes. When she paints the view from her car window, it frames not so much a city as the glass itself and the freeway. This is Southern California, and there is no there there.

The curators, Ian Altevee and Gary Garrels of SF MOMA with Meredith A. Brown and Nancy Lim, give her a central room for recent work. Where they see a culmination, you may see just more of the same. Every time I fall for the beauty or the illusion, which is often, I feel that I should know better. And every time I back away, I feel that, just maybe, she does, too. Celmins had pride of place at MoMA in 2007, for a show of "What Is Painting?" You can find an answer in pleasure, skill, or skepticism—or just a perpetually open question.

Two women

One was born in 1927 and, to this day, is largely unknown. For the opening of a new arts space on Governors Island, she contributes most of the work and its greatest impact. The other, born in 1971, is the nominal star of the show and among the first to exhibit at Pace's new multistory gallery in Chelsea as well. The first lost everything she had in a fire at her Paris studio—and, even now, is rebuilding a body of work at home in the Chelsea Hotel. The other was born in Paris but grew up in Morocco and is still finding her away around New York.  She has appeared in shows of contemporary Arab art and "Scenes for a New Heritage," as if she hardly knew where she belonged.

She has appeared in shows of contemporary Arab art and "Scenes for a New Heritage," as if she hardly knew where she belonged.

Could they feel an affinity? Yto Barrada surely does in making Bettina Grossman, or simply Betinna, her guest. Each has one large work of many parts at the LMCC Art Center, like a living wall. Smaller work hangs together behind a partition, daring you to tell them apart. Barrada's concluding video gives the show its title, "The Power of Two Sons." She means its colorful abstraction to shine like two suns, and she must think of herself and Bettina as shining together as well, as women in abstract painting like those in American Abstract Artists before them. Rather than two sons, she may think of them as a mother and daughter in art, much as the actual daughters of Emily Mason took up painting.

Barrada speaks of overcoming "insularity," like Bettina at the Chelsea Hotel—and of making art about hospitality, solidarity, and care. Those terms have added meaning for an immigrant, especially one from an Arabic-speaking nation, and her largest work on display evokes her displacement. Her hometown has a namesake in Tangier Island, in Virginia, and she stuffs white cages with crab pots from there blackened in charcoal. A row atop the wall consists of cages within cages, but with tears in the wall for breaking through. Bettina, in turn, has fifteen fragments of polished wood set on pedestals—like wings, fossils, or, the gallery says, "ghostly remains of an ancient ship." As a Jew, she has had her sea journey, too.

Other wood sculpture by Bettina, dating to the 1970s, spirals back on itself or fits ingeniously together. On paper, she catalogs forms like these, but with reference to natural growth in leaves. Barrada, in turn, has her Leaf Shapes, one much like an early black painting by Frank Stella, only smaller and, to believe the artist, more organic. She also photographs children at play on the Virginia island, the photos as deliberately clumsy as her video. Bettina may yet have the last word, though, and it is not half as solemn or reassuring. Text on paper runs from expression and repression to regression and aggression, via depression.

She has every reason to run the gamut herself, but does she even exist? Is she a projection of Barrada's sense of displacement and imagination? That would explain, I heard myself saying, why only one gets top billing and the other is maddeningly hard to find online (although she will appear in "Greater New York" in 2021 at MoMA PS1), but it would be awfully self-serving, for all the saving irony and complexity. As I left, I resolved to take both artists on trust, since trust, too, is part of solidarity and care. In fact, she is real indeed, the subject of an award-winning documentary by Corinne van der Borch as Girl With Black Balloons, and a welcome discovery. She is also a welcome back to Governors Island, where the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council has been constructing an airy two-story gallery and café.

LMCC has long supported artist studios here, right next to the ferry from Manhattan—and they look pristine as ever through a locked glass door. The lower-level gallery goes to Michael Wang, with his own leaf forms as Extinct in New York. One of five greenhouses holds tanks for underwater species, while four more hold potted plants. Still more slices of life appear as impressions on paper, although they leave less of an impression. They are obviously not extinct, but they no longer grow in the wild, and plans to reintroduce them into the city's biosphere are unclear. You can be grateful to shows like these that pioneering women artists are, increasingly, no longer endangered species.

Vija Celmins ran at The Met Breuer through January 12, 2020. Yto Barrada, Bettina, and Michael Wang ran ran at the LMCC Art Center, soon to become the Governors Island Arts Center, through October 31, 2019.