Outside the Box

John Haberin New York City

Richard Hunt, inHarlem 2016, and Michael Richards

Richard Hunt is at his best when he can think outside the box—or at least outside the white cube of a modern museum. He thrives on the mass and scale of public sculpture, with more than one hundred commissions to date.

Only, surprise: the Studio Museum in Harlem has brought him indoors. To add to the healthy confusion, it has also commissioned four artists to set up shop in neighborhood parks, as the 2016 edition of "inHarlem." Which has produced truly public art? Each navigates the space between monumentality and community. So does Michael Richards on Governors Island and in the Bronx, between his death and the sky.

Out of the storm

Richard Hunt can boast of a remarkable achievement for anyone, not least an African American. His Hybrid Form from 1972 at Morningside Avenue looks almost like a steam shovel or a sliding pond, with all the power of one and the playfulness of the other. Now "Framed and Extended" shows him making the frame as well as breaking out of it. At the Studio Museum, it confines him to the more private scale of its downstairs galleries. It confirms the drive for meaning and monumentality that so often makes public art like his old-fashioned after all. Yet the mix of small sculpture and works on paper brings him closer to contemporary.

A handout situates Hunt in public places, like his place in Harlem Sculpture Gardens. The form allows him, as he puts it, to respond to the community and its purposes, from skating past to waiting for a bus. "The idea . . . was that you could walk under it or sit on it." Another sculpture doubles as a fountain, without losing its nature as abstraction. That, he explains, is what makes it a hybrid. What happens, then, when Hunt comes indoors, out of the storm?

At his best, he creates another hybrid and a uniquely black abstraction. Each Wall Piece from 1989 takes the form of a rectangle, like an actual box or picture frame, but with additional metal jutting out irregularly from the frame and into the room. It continues the work of his public hybrids, but with an art museum's purpose in preserving pictures in place of the community's. At the same time, the frame imposes limits that a public plaza cannot. Instead of a gathering place, sculpture becomes a space of introspection. In its plain rectangles, it also shows Hunt at his closest to Minimalism.

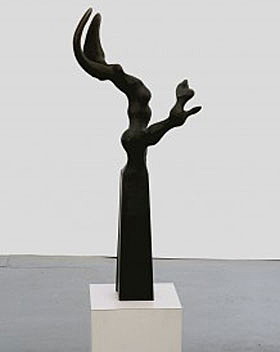

Not that he ever goes all the way to geometric abstraction. Here, too, he treats art as a hybrid. Born in 1935, he rarely gives up the vertical thrust of older sculpture. The show's earliest work, from the early 1970s, forks and spreads upward from a tapering pedestal. It has the self-contained base and smooth finish of Constantin Brancusi, with biomorphic additions akin to Surrealism. Yet it looks more arbitrary than threatening.

Minimalism always thinks outside the box, maybe especially when it is making boxes. It looks not to the aura of the work of art, but to the material object. And then it looks beyond the object to its surroundings and oneself. Hunt, in contrast, rarely settles for the plain sense of things, which is why the rectangles stand out. So do wall pieces from the early 1990s, with the coarse industrial outlines of Melvin Edwards. Prints move between two and three dimensions in a different way, with the dark but softly textured browns of cast, welded, and weathered metal.

Still, he is at his best in public, where the community has its say. Like Eugene J. Martin in collage, he is also returning to his biomorphic roots. The show's latest work, Spiral Odyssey, has him once again building upward from a pedestal. It relates, too, to a recently completed project for a North Carolina park named for Romare Bearden, where it can finally release its energy. From the "built environment," Hunt adds, sculpture has the potential to create "an environment in and of itself." It may not fully break out, but it can still recast the box.

More than a village

It takes a village or two. Simone Leigh has created one, fashioned after Zimbabwe "kitchen houses" of clay and thatch. And then she has dropped it into into Harlem—in the northeast corner of Marcus Garvey Park, where one can no more enter her three huts than the rockface behind them or the housing projects towering above. An artist who has made shower curtains into undershorts, herbal medicines into a poor excuse for political activism, and a woman's back or cowrie shells into obscure objects of desire, she speaks of her village as "locked up while its owners live in diaspora." They could, though, find shelter in the trees overhead or the locker rooms, public pool, and recreation center also in the park nearby. They will have come a long way, and they may have already found a home.

"inHarlem" gives a high-tech label to a low-tech walk through the community, organized by the Studio Museum in Harlem. It extends from Madison Avenue to Morningside Drive to the west—and then another two miles to the north. It invites four artists to mark their own green space, one to a park. And it sees their surroundings as a place to live and to play, even as gentrification brings its displacements. As I entered Morningside Park, a white sunbather lay oblivious to passing eyes, in what once served as formidable wall between Columbia University and a neighborhood at risk. Now the show's very title invites one in.

"inHarlem" gives a high-tech label to a low-tech walk through the community, organized by the Studio Museum in Harlem. It extends from Madison Avenue to Morningside Drive to the west—and then another two miles to the north. It invites four artists to mark their own green space, one to a park. And it sees their surroundings as a place to live and to play, even as gentrification brings its displacements. As I entered Morningside Park, a white sunbather lay oblivious to passing eyes, in what once served as formidable wall between Columbia University and a neighborhood at risk. Now the show's very title invites one in.

Not that the artists are unaware of racism, displacement, and danger. Rudy Shepherd has documented the Superdome as a site of displaced persons after a disaster, and Kori Newkirk has displayed a shopping cart, in "Blues for Smoke" at the Whitney Museum, as an emblem of life on the streets. Here, though, Shepherd marks the north end of the walk in Jackie Robinson Park with a "negative energy absorber." Black Rock, actually concrete over wood and metal, takes its shape from Manhattan bedrock. It means in turn "to dispel people's feelings of racial prejudice, violence, or ordinary disdain by opening them to more compassionate aspects of their personalities." And Newkirk imagines St. Nicholas Park, itself a half-mile rock wall, as "the site for a ceremonial procession."

Well, O.K,, and Shepherd sees Harlem more through the eyes of Henry Moore than of its residents. As for Newkirk, maybe Sentra sounds more like a Nissan model, but it does, he swears, denote "sexy creative energy." Still, anything would look good just past another public pool, and Newkirk knows a thing or two about reaching out. In "The Bearden Project," at the Studio Museum in homage to Romare Bearden, he turned paint cans into a game of telephone. In his own show, six years after his appearance there as an emerging artist, his marks of post-black identity included human hair and beaded curtains. Here reflective strips hanging from goalposts create curtains visible from across the street.

"inHarlem" turns to artists familiar from past shows, which is O.K., too. As curator, Amanda Hunt is bridging the museum and the community. Kevin Beasley appeared in "Fore," the museum's 2013 survey of emerging artists and, like Leigh, as an artist in residence. There Beasley left his mark in stained and folded surfaces. Later, a 2014 show on the American South, he simply amplified the surrounding silence. Now he combines the two by framing a field in Morningside Park with three "acoustic mirrors"—like satellite dishes steeped in torn t-shirts and paint.

The shirts have lost their identity, but the dishes have not altogether lost their sound. Beasley calls them Who's Afraid to Listen to Red, Black, and Green and chooses their colors from the African American flag. The title also echoes Who's Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue by Barnett Newman, the Abstract Expressionist—because Harlem is also part of New York, and it covers a lot of ground. The installation takes considerable hunting out, and the museum provides few clues. (For what it is worth, Beasley claims the park's southwest corner, atop the 114th Street stairs.) It takes more than a village: it takes art and the city.

An airman foresees his death

When an artist dies young, it may do more than cut short a career. It can freeze that career into a single image, where the art would almost certainly have moved on. For Michael Richards, that image has come to commemorate his death, as if he had been preparing for it all his life. In sculpture, Richards himself stands just off the ground,  arms by his side as if immobilized, palms raised in supplication or in hope. He bears the burden or the empowerment of a pilot's full dress, right down to the straps across his chest that both grant him a parachute and hold him in place forever. I thought of a poem by William Butler Yeats, "An Irish Airman Foresees His Death," only Richards was an African American from Brooklyn and Jamaica, the home of John Dunkley, with additional roots in Costa Rica.

arms by his side as if immobilized, palms raised in supplication or in hope. He bears the burden or the empowerment of a pilot's full dress, right down to the straps across his chest that both grant him a parachute and hold him in place forever. I thought of a poem by William Butler Yeats, "An Irish Airman Foresees His Death," only Richards was an African American from Brooklyn and Jamaica, the home of John Dunkley, with additional roots in Costa Rica.

Gilding lends the sculpture both the tackiness of pop culture and a greater glory. So do small fighter planes, like a child's toys, assaulting his body from every side. He has any number of echoes in Renaissance painting, as Saint Sebastian pierced by arrows. He could be plummeting to the earth or rising into the heavens, and Richards himself spoke of "the idea of flight" as that of "being lifted up, enraptured, or taken up to a safe place—to a better world." He seems to speak for all the lives lost in the Twin Towers, like so much art after 9/11 in memory of disaster. Only he made the sculpture in 1999, and he died that awful morning in Tower One.

He also had a few tricks up his sleeve. Others have riffed on the first Christian martyr as well, such as Juan Francisco Elso, Antony Gormley, and Chris Ofili, who convert the arrows into spikes or nails. Richards, though, does not settle for either self-aggrandizement or martyrdom. His title, Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian, shows an awareness of Judeo-Christian tradition, but also of stereotypes and folklore closer to home. Of course, the arrows did not kill the saint, who was then beheaded, and those who tried to pummel the tar baby found themselves stuck. In other sculpture, the artist's forearms become wings, pierced only by feathers—and in one those feathers, motor driven, get to wriggle.

The pilot's uniform, like much of his art, points to the Tuskegee airmen, the first African American military pilots. And Richards sees that segregated unit, too, as at once empowered, ignored, and in danger. In Air Fall, planes dive toward a mirrored target, covered in artificial hair. The same black hair gives a row of helmets the look of fur hats for a long Siberian winter. Drawings invoke the fall of Icarus, the doomed subject that everyone sees fit to ignore for Pieter Bruegel. They offer "escape plans," but on the order of a mere ladder and a grave of chicken bones held together by watermelon glue.

For Richards, death at age thirty-eight came close to aborting his career entirely. He did not flame out in the public eye like Jean-Michel Basquiat, and he has not had much attention since. A retrospective on Governors Island and a later one at the Bronx Museum promise to help, but only barely. Little more than a single room in each limits him to a few works and fewer themes. Screen captures suggest other interests, with allusions to the Middle Passage, Al Jolson, and "Let Me Entertain You." Yet the videos do not appear, and the limits could well be his.

At least the sponsor of the first show, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, makes an effort and recovers a bit of history, while the Bronx adds a fascinating record of his early years in performance. LMCC's "River to River" weekends have largely omitted art, and its exhibitions have left Lower Manhattan behind. Once, though, it had residencies on the ninety-second floor of the World Trade Center, where Richards spent that fateful night. Artists are not supposed to sleep in their studios, but he wanted to continue to work and to have that view of heaven. As another sculpture puts it, of faces smeared with black, A Loss of Faith Brings Vertigo. One can never know whether he had more in him, but one can see him at work on the myth of the overturning of myth.

Richard Hunt ran at the Studio Museum in Harlem through January 15, 2017, "inHarlem" in the parks through July 25. Simone Leigh's pharmacy of black pillows and herbal medicines ran at the New Museum through September 18, 2016. Michael Richards ran at the Governors Island Arts Center through September 25, 2016, and the Bronx Museum through January 7, 2024. Related reviews pick up Simone Leigh in 20018 and at the Guggenheim.