The Shuttered Window

John Haberin New York City

Northern Romanticism and Room with a View

Caspar David Friedrich in Retrospective

Romanticism did not easily sit still. It looked for humanity in nature, like William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge on long walks together by the lakes. It sought a nation in the wilderness, like the Hudson River School. It wandered to the edge of madness, like Théodore Géricault, or with Dante in Hell, like Eugène Delacroix. It found itself with Liberty on the barricades, in a distant harem, or with Napoléon's armies on the march.

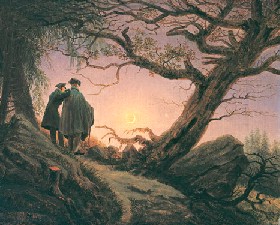

Anita Brookner called her study in heroism Romanticism and Its Discontents, and few seem as discontented as Caspar David Friedrich. Her "hand-over of limpid clarity of utterance to tormented self-absorption" could describe his Wanderer Above the Mists—standing atop a crag, arm akimbo, with a suit, cane, and utter inability to tame the distant mountains. Friedrich's explorers long ago found their hopes wrecked in arctic ice and crumbling graveyards.  His cross on a mountain peak may express an ambivalence about the spiritual or nature, but either way those seem the only choices left. One cannot imagine his Monks Contemplating the Moon content in abbey walks, much less in a domestic interior. An early self-portrait even looks like one of Géricault's asylum inmates.

His cross on a mountain peak may express an ambivalence about the spiritual or nature, but either way those seem the only choices left. One cannot imagine his Monks Contemplating the Moon content in abbey walks, much less in a domestic interior. An early self-portrait even looks like one of Géricault's asylum inmates.

All that makes "Room with a View," an exhibition-length view of the open window in the Nineteenth Century," all the more bourgeois—and all the more exotic. Scenes never leave an enclosed room. Where Brookner described the transition "from stability to flux," everyone sits or stands perfectly still. The only landscape is the city, and even that lies largely beyond shuttered windows. When Friedrich anchors his geometry with just a fragment of a ship's mast passing slowly in the harbor, he could be parodying his own wrecked hopes in The Sea of Ice. The small show offers another version of the Romantic imagination, but it has clues to the more familiar version all the same—and a sequel in a Friedrich retrospective more than a decade later.

Home from the wars

Revisionism begins with the choice of artists. With just thirty-one paintings and fewer drawings, the Met surveys an unfamiliar corner of the nineteenth century—with a full show of nineteenth-century Danish art still to come. Organized by Sabine Rewald, it starts in 1803 with a family scene by Emilius Baerentzen. It peters out around 1860 with dark, colorful, fussy interiors by Adolph Menzel, who approaches the increasing rejection of realism in Symbolism. Mostly, however, it plays out in the early 1820s. It is about a coming of age around 1815, and few will know any of the names beyond Caspar David Friedrich.

It borrows widely from European museums, to focus on German Romanticism and Romantic drawings. Yet it includes French and Italian art along with Germany and Scandinavia, the land of Peder Balke, and several northerners visit Italy, much like Camille Corot a generation after them. Although Friedrich became an icon of Fascism and German nationalism, it is fully cosmopolitan. In one of the few empty rooms, from 1817, a uniform lies tossed onto chair. Loose, open, and colorful, it seems to have too many sleeves and officer's stripes for its own good. Like the show as a whole, it belongs to a freer Europe that has left the Napoleonic wars behind.

Art has returned home. The rooms are practically bare but with creature comforts all the same. A woman by Georg Friedrich Kersting combs her hair, beside a table piled with bonnets. The artists have rejected entirely the idea of a man's world and a woman's world—a world of action and a world of leisure. Men and women meet as equals, and the comic gets along easily with the sublime. In Baerentzen's sitting room, a boy in a triangular paper hat threatens to break up the seriousness, and even his mother does her best to ignore him.

In fact, eyes seem hardly to meet at all. Baerentzen's family circle is pressed up against the square bay of the window, as if sharing an open office. The diligence of sewing contrasts with the luxuriance of a light red curtain draping into the room like a canopy. Kersting allows a couple to meet, but the woman turns away from the man toward the view of a distant mountain. A woman ignores a guitar on the wall to lean over her desk, as plants overrun a man's portrait. Is she corresponding with a lover, turning inward to create love in her imagination alone, or finding a creative and professional life of her own while leaving him behind?

For all that, it is an artist's world, with bare hints of other locations from Dresden to Norway to Rome. The rooms have few furnishings and few luxury goods, although the artists dress as proper middle-class males. The guitar is pretty much the only recurring prop, as befits cultured, creative types (and your joke about Brooklyn here). They often paint one another's portrait, warmly. In Carl Gustav Carus's studio in moonlight, haunting streaks of light and dark penetrate the curtain. An easel with tools of his craft rises upward like an exotic musical instrument.

It is a geometric world, with simple contrasts between light and darkness. More than one group sits practically in the dark in broad daylight. Shutters and window frames define the grid, but so does the ample foreground space. For Johann Erdmann Hummel, ceiling beams project outward, as if in reverse perspective. Outside Baerentzen's window, planar house fronts foretell the flat, even light of Corot's early Roman cityscapes—or even a modern American one by Charles Sheeler in 1925. For Carus, the back of a painting itself blocks the window.

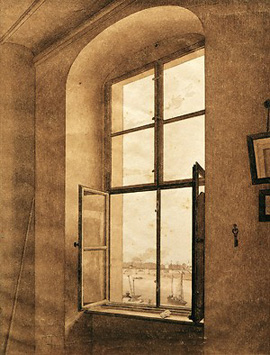

From Vermeer to Modernism

Whatever the world, Caspar David Friedrich invented it at its most luminous. Kersting has more work on display, but Friedrich sets the scene around 1805—at age thirty-one, with a finely wrought river or harbor scene on paper, in a view from the artist's studio. His later ship's mast belongs to Woman at a Window, a painting of his wife from 1822. The mass reinforces the stasis and geometry of the window, shutters, and wall. Nothing else comes close to the deep red and green streaks of her dress seen from behind. Somehow she stands out from the same colors and handling, slightly toned down, in her surroundings.

How strange a world is it—and how unexpected? On the one hand, Romanticism was quite down to earth all along, thank you. Théodore Géricault was merely observing the madness that others had refused to see. The nineteenth century rediscovered Dutch interiors, including Rembrandt and Jan Vermeer. This art modernizes them, much as it rejects Vermeer's division between a girl's longing and the light. Kersting's woman sewing, from 1823, has such a strikingly modern desk lamp that it looks electric. The style is still on sale today.

Not that Romanticism has left its longings behind. It has merely turned them inward, much as Carus's painting bars the window. One can see the inwardness in shuttered windows, mute colors, and glazed mirrors reflecting nothing. One can see it in another mirror, by Hummel, doubling a calmly seated dog. One can see it in the reverse perspective or the frequent shadows similarly projecting forward onto the floor. Logically enough, the outside light creates the inward reflection.

That doubling of outside and in is at the heart of the Romantic imagination. It is an active, creative imagination, like a man's gesture toward Salisbury Cathedral by John Constable. It is the imagination driven outward by thought and inward by light. It allows Wordsworth and Coleridge, a poet and painter for Asher Durand, or Friedrich's monks to find one another in the wilderness, just as Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt went a long way to find America and themselves. Friedrich easily keys up Kersting's haze, especially on paper—with greater detail and an all-over monochrome, occasionally smudging pencil or pen. In one drawing a key hangs on the wall, like a key to the mind.

Sometimes the subject matter makes the contrast between outside and in explicit. Men and women cannot make erotic contact, because there is no space between the exterior and the imagination. Léon Cognier's man set deep within the room does not look out the window, but rather leans by his bed reading a letter from home. As usual, no one captures the paradox better than Friedrich. One room looks out onto a church, like a domestication of his more famous spiritual wilderness. His friend Johan Christian Dahl copies the motif, but with brighter colors and harder edges, as mere adaptation into landscape.

With Wilhelm Bendz., a man leans facing a wall at left, in disconnect from a seated man facing him (in real life, his brother). It is perhaps the last time in the show that the figure at right even thinks of engaging the other—but are they separate minds at all? The man standing at left contemplates a skull. He could be Hamlet, the man at his desk could be the poet, and they could together be rejecting what Michael Fried called Neoclassical theater in favor of the Romantic theater of the mind. It gets hard to know where the imagination ends and the world begins. That insight, though, required Modernism to play itself out.

Distant companions

Friedrich would never be alone as long as he could journey to the forest and the sea. They were all the company he needed, their bare trunks gathering the darkness in winter, their foamy crests the turmoil in his soul. When he faces waters and distant hills, there is literally no looking back. He could have found his double in many another painting as well—or in the companions his doubles took with them to catch the rising moon. The Met has had its focus exhibition on Moonwatchers (in the plural), not its last show of German Romanticism, and I have had my shot at what makes this Romanticism. Rather than start over, then, let me turn briefly to a full-scale retrospective for what makes him Friedrich.

He will never be at a loss for company, but it will never be enough. The men here are anonymous, not the celebrated poet and painter doubling and redoubling the very notion of Kindred Spirits for Durand. Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog , dressed in black and hand on one hip, faces down what he sees, apart and alone, even as his gaze reaches out to infinity. The earth replies with the chilliest of white and uniformly cool colors. Where many a Romantic captures motion and the light, gestures and colors here are barely natural. And their dangerous infinite makes this the Romantic sublime.

He will never be at a loss for company, but it will never be enough. The men here are anonymous, not the celebrated poet and painter doubling and redoubling the very notion of Kindred Spirits for Durand. Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog , dressed in black and hand on one hip, faces down what he sees, apart and alone, even as his gaze reaches out to infinity. The earth replies with the chilliest of white and uniformly cool colors. Where many a Romantic captures motion and the light, gestures and colors here are barely natural. And their dangerous infinite makes this the Romantic sublime.

Friedrich belongs to a long tradition in German art, going back to pale flesh and moist flowers in late Renaissance nudes and Baroque still life. Friedrich took nature as his subject, but not as a naturalist. Unlike John Constable or Beatrix Potter, he left few quick studies of clouds or botanical species. Like a proper student, he built a reputation in drawing before he even approached painting. The Met opens with local scenery and familiar faces in works on paper, including his a self-portrait. Only then could he test the limits of observation and human understanding.

As curators, Alison Hokanson and Joanna Sheers Seidenstein make a point of that slippery contrast between the visible and the infinite, the known and the unknowable. For Friedrich, it is also a struggle for the meaning of vision, between the seen and the imagined. And the imagination wins out. A cross set again and again on a rock in early work, much like the wanderer's tall crag, looks out on a full moon. Sands at sunset become the stage for an allegory of the stages of life.

But what is imagined and what lies just next door? What of a the portal of a church or the western façade of a cathedral? What of an equally grand stone arch? Friedrich keeps you guessing. Facing each, one can feel the same ever-present chill. The show proceeds chronologically and by motif, but Friedrich found his subject and style early on, apart from mistier early skies and the more explicit Christianity, and never let go. So, too, did fellow Romantics like Johan Dahl and Carus, and their works, a handful also on view, are hard to distinguish from his. For all his virtues, sameness means predictability.

The familiar experience has made him a crowd pleaser. Who can resist warm associations and stark feelings? Who can resist knowing what to expect? Still, Friedrich darkens and colors both brighten and deepen in late work, as if the foreground were layered over the whole. His studio window becomes as prominent as what he found on the other side of the glass. The infinite begins with the picture plane and with you.

"Room with a View: The Open Window in the Nineteenth Century" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 4, 2011. His retrospective at the Met ran through May 11, 2025.