A Question of Painting

John Haberin New York City

What Is Painting? at MoMA

The call came in the middle of the night, and the voice on the line sounded hoarse and afraid. "John, it's MoMA. You have to tell us. What is painting?"

I reached for the light. "Go on."

"We have this show, 'What Is Painting.' We have to know."

We have to know

Yeah, right. "Painting is whatever painters do. Easy. Take representative work by the best of them. Put it up. Sell tickets. Done."

"Oh, come on. We have been doing that for seventy-five goddamn years. The public is sick of us. So are we."

My head hurt already, and I turned the light back off. I had a feeling painting was going to look better that way. "How about just the best work, then?"

"You have some nerve. If we acquire art, it is the best. By definition. Because the Museum of Modern Art says so."

This was getting interesting. I decided not to play my hand all at once. "Um, painting is that stuff that hangs on the wall, right? Sort of flat. You know."

"Hey, kid, Clement Greenberg is dead, and if you do not watch your ass, you will be, too. Besides, we have all this other junk lying around, and we promised yet another selection of contemporary art—our fourth now since we built this stupid tower."

This mob has a history

I had better watch it. This mob has a history—and I mean art history. "So go crazy, then. Think of all that trendy work flying off the canvases, covering the entire wall, becoming even an installation. Chelsea can hardly get enough of that macho stuff. I hear talk that your people out at P.S. 1 were behind some of it."

"But we gave Richard Serra the big rooms we always use for that. He threatened to drop One Ton Prop on our biggest donor otherwise—and to seal any witnesses in a Torqued Ellipse. Now we have just half the sixth floor. You put one or two big pieces, and the show is over."

Did anyone ever really look into Arshile Gorky's suicide? You got to be smart to play critic. "Try a theme or two to narrow it. Or give the paintings a little space to talk to each other. Let them make it a game of telephone from room to room, the way you did last time, with 'Out of Time.'

"Yeah, yeah, art as object, art as spectacle, art as abjection, art as artifact, art as this culture or that culture, old media or new media, gendered or neutered, formal or political, pre-this or post-that, blah, blah, blah. Besides, we are not in the business of giving art the last word. We are the curators. We already added a question mark to the title from that old John Baldessari, What Is Painting, because we have all the answers."

"Oh, then show whatever you like!" And they did.

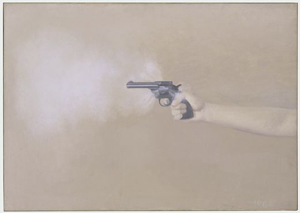

And the results are not pretty. What looks at first like a maze comes down to two long rows of small rooms, each with four works, one to a wall. Call it a postmodern take on the white cube. One can see the problem in the very first room, with that creamy Lee Lozano Hammer, a Philip Guston head, a nude by Philip Pearlstein, and a gunshot by Vija Celmins. None is exactly great, the Celmins looks nothing like her work, and the implicit theme of the human body as a scene of violence only gets in the way. They can hardly enter a dialogue either, because each is shouting.

A wake-up call

A sly curator might be debunking Pearlstein's clinical gaze and his claim to give representation the purity of abstraction. The room might be recovering two women's agency, each in a male world of tools and bullet holes. Instead, it makes all four works look smaller and plainer by erasing differences. In the same way, a harsh light shines down on Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, and Shirazeh Houshiary. The contrast might reveal distinct means and ends, materials and vision, in near monochrome. It ends up with a single, blinding wash of white. No wonder my dream has them calling in a night world of artificial light.

A preference for quotation and appropriation adds a chilly distance even to abstraction, as in selections of Allan McCollum, Sherrie Levine, Blinky Palermo, and Martin Kippenberger. Richard Pettibone's tiny imitations of Frank Stella substitute for the real thing. Several rooms allude to cartoons, but Elizabeth Murray looks all the more cartoonish for that, anticipating Carroll Dunham. Such fashions as the influence of the graphic novel and film culture hardly appear. A youth culture, in fact, comes no closer than Tim Rollins and K.O.S., his efforts to mobilize the streets of the South Bronx back in the 1980s, and I tried to remind myself that it does not stand for kids on speed.

Other shows, like "High Times, Hard Times," have seen Lynda Benglis's poured latex as a transformation of abstract painting. The 3D media here, including a wood frame by Jackie Winsor bound together in twine or Benglis's own ribbon, look like ordinary sculpture. Text appears in work by Baldessari, Christopher Wool, and Barbara Kruger, but in different rooms—and as only a small indication of the roles of words and images everywhere in art today. MoMA allows painting to exchange image for text, but not to mix up the game too much. A muted double portrait by Gerhard Richter, clothed laborers by John Currin, and a cut-off figure by Marlene Dumas seem designed to mute the sexuality and controversy associated with each artist.

The show, in short, does everything it can to steer clear of the canon, but also of outside voices. Perhaps art needs the first after all, to allow the second to flourish. I have never appreciated Francis Bacon, but his triptych startled me. A major work had somehow slipped in, at the cost of obliterating everything around it. The hints of a torture chamber also reminded me how far the show goes to avoid political art.

Occasionally, an unpredictable work makes a painter newly interesting. A small interior by Anselm Kiefer showed him capable of dealing with earth and history on a more human scale, much as in his book art. A rust-colored assemblage by Dorothea Rockburne puzzled me, but it left me eager to see again her folded white surfaces. I had the pleasure of mistaking a Robert Colescott for work of a much younger and hotter artist, Dana Schutz. What will happen next year, with "Color Chart," when the same museum moves from painting to ask, in effect, "What Is Color?"

More often, however, I longed that much more for a question about painting without an answer. Could be the real wake-up call is still to come.

"What Is Painting?" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through September 17, 2007.