From Sweetness to Light

John Haberin New York City

Lucas Cranach and Botticelli's Influence

An influential critic dismisses perhaps the most famous early Renaissance painter as an "ethereal ad man." Exactly what, however, was Botticelli selling? It was not just sweetness and light. In fact, his influence extends to Mannerism and after—including, a friend suggests, to Lucas Cranach. It may not prove the best example, but it helps one ask whether influence defines greatness.

Poster boy for the Renaissance

Not long ago, a New York Times critic dutifully attended a Botticelli exhibition in Frankfurt. Exhibitions of famous Renaissance artists do not come often, and rounding up their work does not come easily. Frescoed walls definitely do not travel. Would it be a knockout or a letdown? For Michael Kimmelman, it was mostly a puzzle.  It only adds to the puzzle of why attribution matters and whether originality is just a modernist myth.

It only adds to the puzzle of why attribution matters and whether originality is just a modernist myth.

Kimmelman dismissed more than just the "annoyingly jammed" and "glamorous crowd pleaser." He targeted the artist, too. He found Botticelli sentimental and trivial—his intense gaze mostly "decorative panache," his subjects "full of exaggeration," and his perspective little more than a parlor trick. The Italian had a few greatest hits, perhaps, for the less discerning. Seeing more, though, just showed Kimmelman how much he disliked.

It seems hardly worth saying, but the best-known quattrocento painter really could paint. The "chill" is the bracing air not of abstraction but of intellectual and religious rigor. At most, Kimmelman points to the limitations of daily arts writing. But was he reacting to the show, the gift shop on the way out, the artist, or his reputation? Was he seeing the painting or its reflection in countless reproductions? Sometimes it gets hard to pull them part.

Great artists often become poster boys (or girls) for a cause. For many, Sandro Botticelli is all sweetness and light, floating on clam shells, and dancing amid the trees. Vincent van Gogh is a madman and Jackson Pollock a force of nature. And that can lead someone who cares about art to dismiss them. Leave them to a public so fixated on a few cultural icons that the Met keeps assigning junk to Leonardo, Michelangelo, or Caravaggio, despite a fine late work in its holdings. However, it can also make one refuse to accept cliché. It can make one look again, as Hoving would have, to linger over art and history.

Critics like Michael Kimmelman are supposed to do just that, but they may not have the time, the knowledge, or the patience. Hey, Botticelli lived a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. More exactly, he was a central figure of the second generation of the Italian Renaissance. He grew up in Florence, where Masaccio, Donatello, Lorenzo Ghiberti, and others had given art a new scale, weight, and humanity. Botticelli served under Filippo Lippi, who had studied with Masaccio himself. The label "sweetness and light," which Botticelli would not have accepted, has dogged Lippi as well, not to mention Fra Angelico.

I can only touch on how much Botticelli goes beyond the erotic charm of Venus and the Madonnas. In his Lamentation, for example, a frighteningly limp Jesus hangs over the massive rocks and gaping blackness of an open tomb. It embraces the arch of Mary's bulking figure even as she, too, nears collapse. I shall not ask what his perspective meant beyond a newly unified space and powerful focus on its inhabitants. Tile flooring like an airplane runway separates an angel of the Annunciation from Mary by a glimpse of infinity. However, in explaining greatness, influence may turn out to be more real than originality after all.

From Madonna to flirt

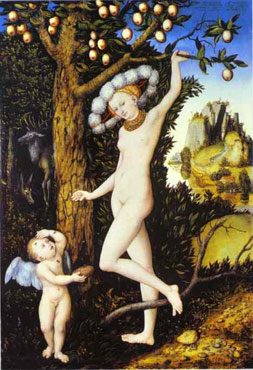

A friend of mine defended Botticelli's relevance—but with an unusual example: Botticelli influenced Lucas Cranach the Elder, a German painter some thirty years younger. Now, a proper judgment would require a trip to Botticelli's retrospective. It may not help Botticelli at that: he is more important than Lucas Cranach. However, it makes an interesting study in the puzzles of originality and influence. Can either one explain what makes an artist great?

Sandro Botticelli was exceptionally influential not so much in German Mannerism as in his own time and his own country. Even his sweetness and light touched the next generation, including early Raphael Madonnas. So did his teaching, with Filippo Lippi's son Filippino Lippi as a student. More important, Botticelli continued to make classical learning, Christian symbolism, drawing in perspective, figures on a powerful scale, and life drawing central to Renaissance ideals, like Piero della Francesca before him. He was so popular that the pope called him to Rome to paint the Sistine Chapel (a wall, not the ceiling). As a follower of Savonarola, he also shared in the religious upheavals that, ultimately, undermined Florence as a city-state and an ideal.

Germany in the early 1500s is far less clear. An emphasis on line has more to with the success of Albrecht Dürer prints. Given the gap in time and space, it is hard even to know what Cranach might have seen of Botticelli, although Venus's bent knee by each artist is suggestive. What he did see, he probably saw in prints, as part of a new Europe with greater trade between nations. That, in turn, would attest to a broader Italian influence on European panting, aside from Cranach.

Germany in the early 1500s is far less clear. An emphasis on line has more to with the success of Albrecht Dürer prints. Given the gap in time and space, it is hard even to know what Cranach might have seen of Botticelli, although Venus's bent knee by each artist is suggestive. What he did see, he probably saw in prints, as part of a new Europe with greater trade between nations. That, in turn, would attest to a broader Italian influence on European panting, aside from Cranach.

The differences between the painters stand out, too, even when it comes to attractive women. Why do Cranach's stand in the nude (or what may look like wickedly unstylish pajamas), with jewelry, shaved armpits and pubic hair, a gaunter build, and at times also a pot belly? Botticelli would have been aghast. Germany may explain a turn away from platinum blonds, but what else was at stake?

As Harold Bloom keeps insisting, influence is always misinterpretation. With Mannerism, as with Andrea del Sarto and his drawings in Italy, make that willful misinterpretation. Like artists today still conscious of Modernism, they could not shake off the Renaissance. In fact, they refused to do so.

With his women, Cranach simply changes the subject. Like Hans Holbein in Tudor England, he alters the terms from Catholic to Protestant, from church to courtliness, and from myth to Renaissance portraiture. He alters them, too, from ideal to expression, from light to decorative color, from lack of fulfillment on this earth to a tease, and from faith to sex. Instead of Savonarola's threat of the end of the world, one has to look forward to Michelangelo's Last Judgment of earthly torments—and, one day, the Baroque. Does that make Botticelli or Cranach more or less original? Maybe or maybe not, but it makes them alive.

Michael Kimmelman's report from Europe appeared in The New York Times on December 3, 2009. A related review looks at Lucas Cranach's role in Martin Luther's Reformation.