Modernism's Mad Men

John Haberin New York City

Alfred Gescheidt and Edward Steichen

Talk about the mad in Mad Men. Both Alfred Gescheidt and Edward Steichen straddled high and low culture, including commercial photography and fine art.

Gescheidt's overlooked body of work offers a shifting portrait of American anxieties and desires. And it does so most brilliantly in a single series, at the dawn of the sexual revolution. Well before self-avowed feminist art, this male photographer took on the male gaze. It would not have half its comedy or its terror if that gaze were not also a New Yorker's. But then Modernism always knew something about when to step away from reality in the guise of revealing it. No wonder Steichen, too, thrived on mixed allegiances.

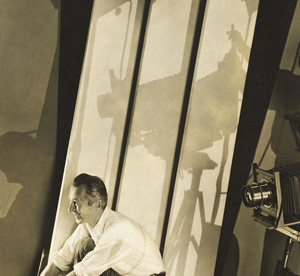

In 1929, he had work to do. A self-portrait shows Steichen kneeling in profile, barely within the frame, sleeves rolled up and ready to go. One may not spot right away his bulky camera, not when its shadow fills the bright scrim behind him with a more alluring image. He had a job to do, and it involved the tools of his trade, high style, and illusion. A look at his commercial work from the 1920s and 1930s asks what makes photography fine art. (A separate review turns to Steichen and American Modernism.)

To light up America

Still trying to quit smoking? You could morph the end of the cigarette into a combination lock—or light it with sparks from sticks of dynamite. You could die, impaled on a cigarette, or go up in a puff of smoke. You could lose yourself forever in a vending machine wanting more. You could put the cigarette on the couch to analyze its appeal, your failure, or therapy itself. Then again, sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

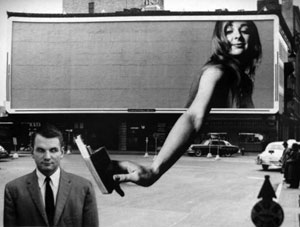

Alfred Gescheidt thought of all these and more back in 1964. He works seamlessly, with double exposures, overprinting, and shifting lenses. They leave the illusion obvious but the fakery behind its marvelous humor impossible to tease apart. Like all Gescheidt's photographs, Thirty Ways to Stop Smoking is not about advice, but desire. A woman even reaches out from a billboard to offer a cigarette. Not that the man on the street, trapped in his suit and tie, can respond.

People used to say that the Theater of the Absurd is one part vaudeville and one part avant-garde. One could say much the same about Gescheidt, only one thing: be sure to update it for the visual arts and for America. In fact, I already have. I spoke of vaudeville, where a French playwright like Eugène Ionesco would have known the theater of the boulevards, but I might just as well have recalled the classics of silent comedy. For the photographer, a man hangs from the side of a skyscraper by his fingernails, much as Harold Lloyd clung to the hands of a clock—and who is to say who is funnier or more in fear of his life?

Gescheidt, who died in 2012, knew fine-art photography as well as anyone, without the artsy bias of the AIPAD Photography Show. He took to the subways for his first major series in 1951, much as Walker Evans had at least ten years before him. When he photographed skaters at Wollman Rink in Central Park, in 1965, they seem caught in the stillness of their own long shadows out of Paul Strand. His very vocabulary of black and white, photomontage, and a great deal of sex may make him the last and truest American Surrealist, give or take Llyn Foulkes in California. He looks forward as well. When he shoots the curbs of Manhattan in wild and fragmentary perspective, for the series "Street Cleaner" in 1951, he shares that fascination with what Lee Friedlander was to call "America by Car."

And this is most assuredly postwar America, of men on the subway isolated by light and shadow rather than joined for Evans in the community of the Depression. The Cold War brings irony and dread, from a woman quite literally walking on the head of a pin to a man clinging to the side of a skyscraper. The 1960s loosen up, even as the pressures build. The white shirt and narrow tie give way to the young urban professional—stuck in his own briefcase with a slide rule, too many papers, and "creative department classics." It is increasingly a politically charged and polarized America, of George Wallace and Shirley Chisholm inserted into Grant Wood's American Gothic in 1970, for Politics Makes Strange Bedfellows. Upheaval peeks out through the horseshoe snagging the Washington Monument, with another on its way through the sky.

It is an America confused by its own optimism, as for Martin Adolfsson, like a man with a bathing beauty at his fingertips. It is also the America of commercial photography, the business with which Gescheidt supported himself all his life. A snake coming out of a man's fly, its skin all too close in texture to his jeans, could belong to a Levi's ad. No wonder money looms large too, like the long shadow of the words mutual funds. More broadly, the photographs, like a killer ad, aim for that instantly memorable image, centered around a person and a product—only to take on afterward that extra punch of a title. And nowhere does Gescheidt sustain that formula longer or more ingeniously than in Thirty Ways to Stop Smoking.

Quitting time

His gallery introduced the photographer in 2009, with work starting in 1949, just when Ionesco was wrapping up his first comedy, La Cantatrice Chauve ("The Bald Soprano"). And no question but Gescheidt's combination of high and low, as well as comedy and terror, was then hitting its stride. Born in 1926, only two years before Andy Warhol, he lived and worked through Pop Art. Still, he hits his stride before Warhol, with deeper connections to the past, and for him popular culture is the medium more than the subject matter. Like advertising, he is representing desire rather than photography. And now with that one series on view in its entirety, the desires keep coming.

Yet the old allure may be starting to fade after all. Hey, it is already legit to worry about how to stop smoking, much as a movie star's ever-present cigarette here gives way to the scrutiny of ashes under a magnifying glass. There is a time to laugh and a time to quit. And the allure of the male is fading most of all. He is so easily caught in a mousetrap, a herd of sheep, or a bottle. When a man with a mustache, a cane, a pocket handkerchief, and a bow tie poses beside a little girl nearly his size as his Lolita, he is anything but debonair, an intellect, or a victim.

The man comes right out of the theater of the boulevards. Gescheidt needed rediscovery, in part because it took so long for the distinction between high and low culture to crumple, with surely a nod in acknowledgment to him. He also drew on early Modernism, at a time when art, like science, was supposed to march on. He also was more gentle than satirical, when the neo-Pop of the 1980s demanded otherwise. He leaves no doubt about his sympathies, political or otherwise. Yet he always leaves in doubt whether to feel most the comedy or the terror.

Photoshop has made manipulation a way of life, and art has responded by harping on rough edges. Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg insisted on them long ago, long before Warhol's influence or Rauschenberg collaborations came to stand for changes in contemporary art. David Salle and the "Pictures generation" made the edges rougher. Going back further, one could call it a battle between Man Ray and Max Ernst, and Ernst's mad collage has won out. For now, in dreams begin irresponsibilities. Gescheidt's age still dreamed deeply but trusted surfaces.

Gescheidt learned from modern photography's finest artisans of the surface. He studied design, and, yes, his images appeared widely as advertising. They also peer beneath its surface. To this day, their surface looks familiar enough to be worth peeling away. I mistook the woman's slim offer of a cigarette pack for an iPhone. Still, he may depart most from convention as photojournalism—and as a chronicle of a quarter century of desire.

Frustrated desire was at the heart of Gescheidt's special comedy and anxiety all along. The camera's eye is always male, like the photographer himself looking back from a pair of binoculars, but then an anonymous hand grips them both. A drawbridge parts for a nude flat on her back like a barge, while a man treads warily on a carpet of breasts, like walking on eggshells. Another naked man stares up in wonder at an enormous naked crotch, but there is no turning back. He is already well between her legs, without so much as nicotine to calm his nerves. Even without a cigarette, this work smokes.

Advertising Modernism

If Edward Steichen relied on the tools of his trade, high style, and illusion, so does the glossy magazine business, and he had been chief photographer for Condé Nast since 1923. Any self-portrait is a doubling, but Steichen photographed himself much as he would treat Maurice Chevalier, using multiple light sources to give the entertainer a pair of whirling shadows. Chevalier might be singing to the audience while dancing with himself. For Steichen artists, too, had style, like Charles Sheeler with his hands in his pockets, ever so dapper and casual. Eugene O'Neill adopts a pose and a sullen glance that would do his leading actors proud. His wife, Carlotta, who had herself held the stage, shows not a trace of her encroaching madness.

"Edward Steichen in the 1920s and 1930s" shows off a gift to the Whitney of his work for Vanity Fair and Vogue, where he remained until 1937, well before Irving Penn. Those years have already him earned a book and a much larger show at the International Center of Photography, in 2009, but they benefit from the intimacy of the museum's first-floor gallery. One can get to know "Mr. Sandburg" (Carl, to you) and his wife at home and Jacob Epstein, the British sculptor. Endless Column by Constantin Brancusi rises like a ghost from behind a fence, within the photographer's own garden. Steichen's daughter resembles a stage character, perhaps Ophelia—the very device that Mitchell favored sixty years before. Steichen is within his circle, but it is the world of stage and screen all the same.

His commercial photos recall early Modernism, but as theater. An apple, warts and all, on the curved outline of a table could be a subject for Strand. Its title, An Apple, a Boulder, a Mountain, France, shouts its loyalty to the still lifes and mountains of Paul Cézanne and Cézanne drawing. Yet it also speaks of playing a part. Foxgloves have the spare beauty of flowers for Georgia O'Keeffe and O'Keeffe drawings, with an old-fashioned precision. Yet instead of O'Keeffe, as sitter or companion for Alfred Stieglitz, one has Marlene Dietrich, "the Teuton siren."

His commercial photos recall early Modernism, but as theater. An apple, warts and all, on the curved outline of a table could be a subject for Strand. Its title, An Apple, a Boulder, a Mountain, France, shouts its loyalty to the still lifes and mountains of Paul Cézanne and Cézanne drawing. Yet it also speaks of playing a part. Foxgloves have the spare beauty of flowers for Georgia O'Keeffe and O'Keeffe drawings, with an old-fashioned precision. Yet instead of O'Keeffe, as sitter or companion for Alfred Stieglitz, one has Marlene Dietrich, "the Teuton siren."

Steichen was always the most atmospheric and traditional of American modernists, always in love with shadow. It all but consumes Thomas Mann, and it gives a writer like H. G. Wells and a public figure like Winston Churchill, both seated, much the same bulk and dignity. If a performer did look sufficiently serious, Steichen is happy to help. He presents Charlie Chaplin not as the tramp of comedy, but in a suit—and divides him vertically with light and darkness like a map of the unconscious. Steichen also gives actors an assist by encouraging them to improvise while in character. Lynne Fontaine steps out of O'Neill's Strange Interlude just long enough to frame a mournful child.

Nothing is beneath him, including advertising, and here, too, sophistication is the name of the game. A lipstick ad slips in a man among a woman's multiple reflections, because even a make-up mirror holds more desires than one knew. Rows of silverware against a black surface approach a mathematical composition, Churchill fronts a demand to repeal prohibition, and a nude promotes Cannon Towels. Did she have a stain that nothing else could remove? In an ad for a hospital, people line a two-tiered stairwell, like immigrants at Ellis Island for Lewis Hines. Are those hungry masses yearning simply to breathe?

One should not think of these photographs as acts of subversion like Gescheidt's. They are acts of revelation. They flatter a magazine's readers by taking them behind the scenes. They are also creative acts, for a photographer working his own way through convention. One of the first photos, of a modern dancer's ecstasy on the Acropolis, is also among the hokiest. Maybe Steichen never does get over the idea of art as a mad ritual, but he can start to place himself in the company of the new.

Alfred Gescheidt ran at Higher Pictures through October 24, 2009, and through August 2, 2013, Edward Steichen at The Whitney Museum of American Art through February 23, 2014. Related reviews look at other practitioners of the male and female gaze, such as William Copley, and place Edward Steichen in the company of Paul Strand and Alfred Stieglitz. Another looks further at magazine, commercial, and fashion photography, in a show about the "Modern Look."