You Ought to Be in Pictures

John Haberin New York City

The Pictures Generation

Even if you were keeping a close eye on Soho in 1977, you might have missed "Pictures." Even after, you might not have heard much talk about the exhibition. Regardless, you would almost certainly have caught the buzz.

"The Pictures Generation: 1974–1984" takes that show as a defining moment. It misses the big picture. It does not even care all that much about its themes of irony and appropriation. It does, however, supply a timely history lesson. Art is still struggling to decide whether Postmodernism means critique, pluralism, or anything at all. The Met looks back to when artists were wondering the same thing about the twentieth century.

Something old

"Pictures" brought together Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, and Robert Longo at the Artist's Space. Within a year, the nonprofit also showed photographs by Cindy Sherman and Louise Lawler. I was just out of college then, and I, too, missed the party but felt the buzz. The artists might have liked it that way. Like a morning after party for someone else's hangover, they tore art out of other people's psyches.

They quoted what had already vanished or had never existed in the first place, but its traces were everywhere. Short film clips lingered just a little too long for comfort over familiar objects. Paintings and photographs recycled images from magazines and old movies. When that failed, they invented the movies. They may have been the first generation raised on TV, but their style and sources were decidedly low tech. It was not so much intoxicating as chastening.

Formalists back then insisted on art as an object and a practice all its own. Others had pushed art into earthworks, politics, and performance. A resurgence of painterly expression from Europe was on the horizon. In all these ways, art sought to combine public gestures and conceptual rigor. The curator of "Pictures," Douglas Crimp, saw instead the power of images. "After being particularly interested in conceptual art, performance art, and so on in the early '70s, suddenly I was seeing people making pictures, and that was something new."

It was new, but also used, what the Guggenheim has called "Haunted." Levine photographed photographs—from magazines to, a few years later, classic images by Edward Weston and Walker Evans. Goldstein spliced together the MGM lion roaring over and over again. Longo borrowed a film still from Rainer Werner Fassbinder for images of men struck by a bullet. Cindy Sherman was working on her own Untitled Film Stills, in black and white, with herself as the only actor. Brauntuch and Annette Lemieux went all the way back to Fascist or Maoist rallies for their dark, almost inscrutable paintings.

It was also a rebuke. With Goldstein, a graduate of the California Institute of the Arts, it was a rebuke to the New York scene. His clips of light slowly crossing a table knife or leaves falling on an empty chair echo Hollis Frampton's shot of a lemon, a six-hour movie by Michael Snow that may at first seem more like an eternity, and the still longer underground film of the Empire State Building by Andy Warhol, and indeed Warhol's last decade corresponded with the Pictures generation. Goldstein's films ran only a couple of minutes, though, unlike Warhol's Empire, and his moving pictures moved. He seemed to care whether one enjoyed simple things. As for whether one called them art films or even art, he hardly seemed to notice.

They also rebuked what Rosalind Krauss in 1981 would call the "originality of the avant-garde." With Levine and Sherman, that rebuke has feminist implications. Women might still find themselves trapped on camera. By staging or rephotographing the image, however, they could claim the images for themselves. The images might date to the 1930s—or just look that way. Either way, they put a stop to Modernism's history.

Something new

In "The Pictures Generation," they have plenty of company. Like Goldstein, four of its other artists studied at CalArts with John Baldessari—Barbara Bloom, Matt Mullican, David Salle, and James Welling. Thomas Lawson, who preferred painting for his images of a battered child, is now its dean. Still another Southern Californian, Sarah Charlesworth appropriated newspaper photographs of suicides. However frightening the subject, they gave it the plainness and impersonality of a mass-media filter. Bloom mixed invented travel posters and real ads for window fixtures, Mullican devised a system of graphic signs that mean nothing at all, and Charlesworth cherished the grain and blur of blown-up images.

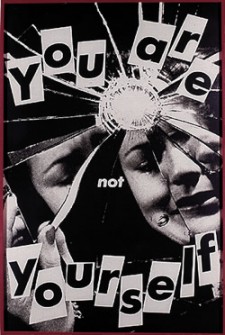

Like Longo and Sherman, three others studied in Buffalo—Charles Clough, Nancy Dwyer, Michael Zwack, and (not in the show) Andrew Topolski. Like Sherman, too, Dwyer put women's poses through their paces. Barbara Kruger and Laurie Simmons also treat high and low culture to a feminist critique. As Kruger's text across a female profile reads, "Your gaze hits the side of my face." Simmons combined photographs of a camera on two scales, like mother and child. In her color collages a few years later, cameras and other objects have Barbie doll legs.

Lawler edges further toward a critique of art as commodity capitalism. She photographs private art collections, with all the room furnishings in place. Sometimes they seem pathetic. What kind of person would stick an abstraction by Robert Delaunay behind furniture? With decorative porcelain in front of a Jackson Pollock, they can seem suspiciously beautiful. One wonders what she told the collectors when she asked for access.

Kruger worked in magazine publishing, where her X-Acto knife led her both to collage techniques and to such images as a shattered mirror. Richard Prince, too, latched onto commercial photography the hard way, from a day job. Like Welling a year or two before, he saw Marlboro ads as the summation of masculinity and the American dream. James Casebere, too, had the American dream in mind, when he subjected storefronts and subdivisions to raking light. He was actually photographing his own models in folded paper, years before Thomas Demand. As for masculinity, it dominates Zwack's concert posters and handmade toy soldiers.

Before long, everyone else felt the buzz, too. In Soho, Metro Pictures and Mary Boone galleries latched onto the new style, and Brauntuch showed at both. MoMA snatched up Sherman's Untitled Film Stills, just as she was moving on to still more self-revealing and self-concealing self-portraits in color. After novels like Bright Lights, Big City and Less than Zero, Longo's dance of death took on a new meaning, as emblems of yuppie nightlife. Mullican and Allan McCollum were not exactly ubiquitous, but they did their best to look that way. Mullican had his own sign system, like security alerts in corporate offices, and McCollum packed show after show with empty picture frames.

For perhaps the first time since Clement Greenberg, the style's backward glance made criticism an essential adjunct to art. Andy Grundberg in The Times called it A Crisis of the Real, and a 1983 collection of articles edited by Hal Foster, The Anti-Esthetic, soon served as a manifesto. Crimp contributed, with an essay "On the Museum's Ruins." Of the handful of photographs, Kruger, Levine, and Sherman supplied three. Foster, still in his twenties, for a while gave Art in America a theoretical depth as well, before moving later to academia and October magazine. The same years saw publication in English Jacques Derrida's Writing and Difference and Margins, Jean Baudrillard's Simulations, Julia Kristeva's Revolution in Poetic Language, and Richard Rorty's Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature.

Something borrowed

With all that buzz, how could anyone have missed the founding event? For one thing, so much else was going on. One can forgive Douglas Eklund, an associate curator in the Met's photography department, for claiming a generation. Nowadays, art as commodity has largely lost its bad associations. A museum show is a boast, like "The Generational" now at the New Museum. Still, if any generation had a defining moment, this one had more moments than one can count.

For maybe the first time since early Modernism—and the last time before today's chaos—art had many movements, often at war. Recent shows have captured many of them, and they have very much to do with making pictures. "High Times, Hard Times," "Summer of Love," and the Broida collection have shown post-painterly abstraction spilling into "new image" painting and excess. Sperone Westwater Fischer gallery was already bringing European art to Soho. With Georg Baselitz and others from Germany and Italy, Neo-Expressionism was soon on its way. Julian Schnabel gave it an American expression.

Much else had little to do with canvas, but here, too, artists were borrowing from strange places. Judy Chicago added an earnest feminist history that feminists of the "Pictures" generation might have parodied. The 1980 Times Square Show, with Kiki Smith and others, led to East Village art. That same year, with Walter de Maria, the Dia Foundation transplanted land art like that of Robert Smithson indoors. The Anti-Esthetic reflects that impulse, too, with Krauss on "Sculpture in an Expanded Field."

All these movements helped to dissolve the postwar consensus. That consensus was pretty tenuous anyway. Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg had been squabbling all along. Pop Art, Minimalism, and the 1970s only made things worse, and Robert Indiana anticipates the future when his art lectures on politics and love. An influential essay on the male gaze, "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" by Laura Mulvey, already appeared in 1975, just when William Copley was turning hookers into Pop Art and Martha Diamond was taking to the urban sky. Hanna Darboven in Europe and Eleanor Antin in California were indulging in role-play around the same time as Sherman, and neither makes it into "The Pictures Generation." Nor do Jenny Holzer or Martha Rosler, whose mix of politics, text, and appropriation appears in The Anti-Esthetic.

All these shared, too, with the "Pictures" generation their uncertainty about what it meant to exploit modern art. The Anti-Esthetic captures that uncertainty. It ranges from Jügen Habermas's defense of Modernism as "An Incomplete Project" to a scathing assault by Craig Owens. For Owens, do not dare to suggest that race, class, or (goodness) art's self-reflection might complete a feminist critique. One might as well say that women are incomplete without men. What the argument lacks in coherence it makes up as a sign of its times.

"The Pictures Generation" has the same ambivalence ten times over—what I have called the postmodern paradox. The past is dead, and to prove it quote the past. Modernism is the power structure, and Modernism is over and done. With "The Pictures Generation," so perhaps is the "Pictures" generation. Intriguingly, one enters through the Met's new photography galleries. One exits through a gallery used for museum blockbusters.

Something blue

One might have missed the founding event, "Pictures," for one last reason: it may not have founded the "Pictures" generation. Besides, it included a lesser-known artist not at the Met, Philip Smith. (Crimp had already edited him out of the story, by omitting him from an influential article based on his catalog essay for "Pictures.") Rather, "The Pictures Generation" uses that show as the start of a revisionist history.

Think first of a sea change in New York City? The Met wants equal time for California and Buffalo, although not for Meyer Vaisman in Spain, and the artists in "Pictures" exemplify that. One could easily call the exhibition the CalArts generation. Think first of irony, feminism, or theory—with an influence on artists of the male and female gaze like Andrea Fraser and Hannah Starkey today? The Met wants equal time for male fantasies, like those of Prince, Welling, Longo, and Zwack—as well as for macho performances by Eric Bogosian and Glenn Branca. The curator says that the women looked "affectionately" at their "boy toys," but I want my anxiety back.

The exhibition even wants to eat away at the importance of appropriation. Before long Welling moves from sunsets and cigarette ads to irregular black blotches, and the two strains have since come together in his gleaming, almost abstract nude photography. Clough could be glibly mocking Abstract Expressionism or glibly imitating it. Paul McMahon's red dots do much the same for geometric abstraction. When the curator calls them, Zwack, and Dwyer overlooked geniuses, he is making a great deal out of pretty lousy art. He is also seeing a newfound affection for art itself.

Affectionate or not, appropriation has become a norm for installation art now, even if ham-fisted irony, as with Mark Flood, is already looking stale. This show rounds out the story of how it came to be. Before Untitled Film Stills, Sherman posed for a row of snapshots in black and white, lipstick, and exaggerated contrast like clown makeup. One can see her in an interview, slight and attractive, explaining her interest in popular culture. Salle worked in photography, too, before his and Eric Fischl's chilly paintings of sex. He juxtaposed four women of different ages sipping coffee, like an advertisement for growing up—and two more ghostly photographs flank a room of flashing lights on the floor.

A gallery exhibition of early Barbara Kruger this spring brought home how many of her words and images have become second nature. "Who will write the history or tears?" It sounds more relevant than ever after torture memos. So does "Admit nothing Blame everyone Be bitter," with its hands meeting across a map, like God's creation of Adam. Charlesworth's shadows falling to their death now seem like echoes of 9/11.

Longo is still playing with boy toys. His newest charcoal drawings, on a mural scale, tackle a rock concert and a cowboy hat. Others evoke a primeval forest and a cathedral. As ever, they look simple-minded, and as ever they aim to impress—and they do, despite oneself. His dying or dancing Men in the Cities look great in the Met's lobby. They could make up for many bad pictures and a marginalization of politics, feminism, and the sweeping changes in a generation to come.

"The Pictures Generation: 1974–1984" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through August 2, 2009, Barbara Kruger at Skarstedt through April 18, and Robert Longo at Metro Pictures through May 30. Douglas Crimp was speaking in a recent interview with WNYC.