The Art of Photography

John Haberin New York City

The 2022 AIPAD Photography Show

Sam Contis and Time Management Techniques

There is no getting around the elephant in the living room. Maybe not literally, not when a giraffe peeps in through the window of a house to small for a circus. Not, too, when a peacock appears as if by magic in a palatial interior and goodness knows what sprawls on an actual living-room floor. Dovima, the fashion model, dances with elephants in Paris, but at the Cirque d'Hiver.

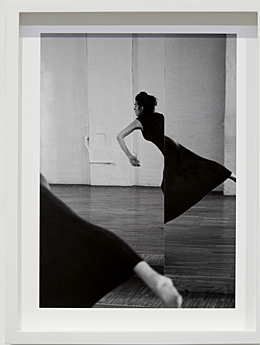

No, the unspoken word is that an art fair is not in the least a snapshot of photography in the present, and it does not mean to be. The 2022 Photography Show sees the medium as ever so desirable. A photo here is a work of art. If that sounds a little much, Sam Contis shows that the artful need not preclude seeing afresh—and seeing another art form as well. It also sees a woman's autonomy in connection with a woman's body. In every sense of the word still, her subject is still dancing.

Lew Thomas could not have seen me coming back in 1971, and yet for a moment I could imagine that his thirty-six images were counting the minutes of my visit to the Whitney. But no, the clock face belongs to a darkroom timer—and its passage from black at left to white at right to stages in a darkroom from negative to positive. Photography's art takes time, and Thomas records the seconds. It also marks time, for his wall of photos is TIME EQUALS 36 EXPOSURES, the number in a roll of film. Developing them all takes managing time as well. Now photos from the collection count the ways, as "Time Management Techniques."

The elephant in the living room

What qualifies as art photography? It depends, of course, on what qualifies as art, and that keeps changing. Art today refuses to set itself above craft or, for that matter, fashion. Shows have called attention to magazine photography and photography by women, as inseparable from the very image of the "new woman" and the "modern look." Art cannot set itself apart either from politics and gender. It has revived documentary photography and commercial agencies, with as artful a photographer as Henri Cartier-Bresson now squarely within both. Portrait photography since Cindy Sherman can no longer see real life apart from the movies, and street photography since Garry Winogrand and Diane Arbus insists on the disturbing truth.

The Association of International Photography Art Dealers has none of the above. Richard Avedon shot the elephants far earlier long before his own portraits, in 1955, in Harper's on behalf of Dior. Nor does it distinguish genres apart from art. Right on the way in (with Robert Koch), Mimi Plumb presents street life as perfectly composed, while Nadav Kander and Edward Burtynsky present landscape as close to abstraction. Obscura, a Santa Fe gallery, opens its booth with the glamour of Central Park in the shimmer of artificial light. (It also has photographers from London and beyond.) Joel Meyerowitz (with Howard Greenberg) captures a young woman outside a fast-food joint and Gordon Parks a black mother and daughter looking into the windows of a clothing store with mannequins, but close to models themselves. When Irving Penn (with Boston's Robert Klein) poses a hooded Pablo Picasso and Alfred Stieglitz (with Deborah Bell) a young John Marin, painters become celebrities as well

The key is artifice. Edward Steichen pictures a formidable matriarch. Photocollage by Anastasia Samoylova (with Laurence Miller) leaves one remembering first and foremost an eye. Yoko Ikeda (also with Miller) uses saturated colors to make bridges and dams newly inviting and newly strange. Several exhibitors display early photography, going back to before the American Civil War or Maxime Du Camp in Egypt. The century of Henry Fox Talbot or Gustave Le Gray (with Hans P. Kraus, Jr.) and Julia Margaret Cameron needed a costume drama to justify photography at all.

The digital is rare, and photographs of photographs are out of the question. Photography here is way too precious for such things. Booths place older work alongside the new, to show that old belongs in prime time and the new in museums. The supernatural resolution of old-world libraries for Candida Höfer, not in the fair, attests to her artifice and their history. More intricate interiors serve Karen Knorr (with Augusta Edwards) instead as precious backdrops to the present—and that peacock. Saïdou Dicko (with Atlanta's Jackson Fine Arts) gives Africans a decorative backdrop, too.

None of this is to dismiss AIPAD, which has found its place—and not just with an often overbearing style. The fair, which once held court in April, between months for New York art fairs, has joined peak week in May. It has just under fifty booths, on two floors of Fifth Avenue south of midtown. It may seem as if the lounges outnumber the exhibitors. It has the occasional single-artist presentation as well, including portraits by Joel-Peter Witkin (with Baudoin from Paris) and Tony Vaccaro, who photographs Gwen Verdon on her balcony and the glamour of a "fashion train."

It also offers a reminder that, after too many closings, galleries devoted to photography still exist (although Higher Pictures appears in another fair, the Independent). Howard Greenberg is still preserving the last century's history, with James van der Zee in Harlem and Weegee. And Yancey Richardson, for one, still keeps it contemporary with Guanyu Xu, John Divola, and Carolyn Drake—Xu with an interior of his own assemblage, filled with images. Not even this fair can give up on diversity as well, with Eli Reed among Blacks in America (with Keith de Lellis) and an abundance of women. Lora Webb Nichols (with Danziger) gives portraiture a context, in the American West. Women can be photographers and cowboys, too.

Still dancing

So when does photography become art? Is it when one remembers the photographer and the image more than the sitter, her glamour, and her clothes? Not with Sam Contis, who privileges none of the above but with an eye to them all. Her show's title, "Duet," marks photography as a collaboration, but with what or whom? It might be a singer, Inbal Hever, or the composer whose work she sings. It might be the space of the gallery or the space through which they all move.

It took a long time for many to accept the very thought of art photography, but now it is a commonplace. At the same time, privilege itself in art has taken its hits, and Contis, too, takes it down a notch. She and Hever are both in performance—only it might be already past or never to come. One can hear the music through two small speakers on tall stands within the gallery. They are as prominent as the framed photos, which show the singer in rehearsal or halfway out of the picture. The two bodies of work, rehearsing and recovering, are a duet as well.

In the first, Hever appears in profile, several times over. She might almost be crying, and who is to say whether the rest is dictated by exhaustion or the score? She holds a tuning fork, not that one can recognize it, and dances to her own reflection in a mirror in black and white. She brings her hands, fingers spread, to her open mouth as if in pain. She can seem close to abstraction, even as her image, crisp or blurred, threatens to slip away. Her black dress has its own beauty in the shallow space of a print, while cutting off almost everything about her.

In the second series, with its own room, she gets close enough at last to see the light. It appears through a curtained window, layering the space and setting limits. One can glimpse the city in the distance, tiny and out of focus, or nothing but the light. The singer presses up against the curtain in longing for a quiet apart from the performance, the quiet of day. And then, window wide open, she turns back to work. She leaves behind a view through the window of flowering trees like a curtain in themselves.

In the second series, with its own room, she gets close enough at last to see the light. It appears through a curtained window, layering the space and setting limits. One can glimpse the city in the distance, tiny and out of focus, or nothing but the light. The singer presses up against the curtain in longing for a quiet apart from the performance, the quiet of day. And then, window wide open, she turns back to work. She leaves behind a view through the window of flowering trees like a curtain in themselves.

Contis is asking what constitutes the picture, the space, or the performance. "I started to think of this as akin to the body bringing air in and pushing it out," she says. "The windows became ways of thinking about interiors and exteriors, and the space of the studio as another body." Bodies have been her subject before as well. She last showed boys preparing to swim or to play, but seemingly ready to fight. She has photographed others asleep but seemingly injured or dead.

She has sought the living body in found objects, too, like a cascade of plastic bottles. Now she seems closer to accepting photography and its beauty, as loaded a term as that may be. She appeared with new photography in 2018 at MoMA, and she seems past making existential statements—so long as she can embrace the limits of human comfort or the light. The score, by Chaya Czernowin, is quiet and comforting, like much sound art, including the background to Minimalism by Jennie C. Jones at the Guggenheim this spring. The close-ups of the window mark the vegetation as an artifice itself. And that leaves the singer, leaning up against her personal limits and the light.

Taking time

Was Susan Sontag "Against Interpretation"? A modest show is "against immediacy" and its moment of truth. The curator, Elisabeth Sherman, denies that every photograph captures a moment in time—for Cartier-Bresson, the decisive moment. The Morgan Library already fought for the "extended moment," but the Whitney sees a greater urgency in the passage of time. It connects capturing the moment to corporate demands "to structure and regulate our days," in the interest of profits and productivity. Shannon Ebner, for one, never gets past the letter A. She photographs whatever instances of it she can find in New York, converts them into posters, and slaps them around such upscale sites as the Hudson Yards.

But wait a second (or maybe two). Surely photographers have always had their darkroom timers and shutter speeds. Surely finding the decisive moment means throwing most exposures away. If anything has changed, it is because smartphones have rendered technique and selectivity obsolete. When Corin Hewitt spent five days in the old Whitney cooking, collaging, and documenting every minute, he was already halfway there. When Dawn Kasper invited her audience to leave something and photographed What People Had Given, she was well on her way.

Surely, too, "time management" here refers to the photographer, not the oppressor. Sky Hopinka uses his skills to recover Native American lands. E. J. Hill uses his to pose on a pedestal as a hero of the Spanish American War, his skin as white as stone. It is chastening, chilling, and funny. And yet both are standing outside of time while sticking to the moment. Hopinka inscribes one image being here right now.

The museum invokes three ways of passing time. Photography allows for personal histories, records of performance art, and reflection on the medium itself. Muriel Hasbun evokes her lifelong journey from the Middle East to the Americas by half burying a snapshot of her grandfather among the memorials in Washington. Darrel Ellis wheels a photo of his late father down the sidewalk, bringing him physically into the present. Hewitt, Kasper, and Hill have their performance, Thomas his exposure times, and Blythe Bohnen a bit of both. She marks four points before photographing the trace of her hand connecting them.

One might just as easily, though, think of each artist as working in a traditional genre and subverting it. Hasbun has her buried portrait, Ellis his street photography without life on the street. Hopinka has his landscapes, Ebner her cityscapes, and Kasper her still life. Still others have abstraction. Bohnen's luminous tracings recall photography without a camera from Man Ray to Wolfgang Tillmans. And the Whitney punctuates them all with photographs of negatives, by Katherine Hubbard, embedded in ice.

As with her negatives, frozen in time, they all struggle with permanence, duration, and immediacy. They struggle, too, to stand apart from works not on display—like Lorraine O'Grady in performance as Mlle Bourgeoise Noire. And they all have a higher commitment to photography as art. Hopinka and Hewitt bring vivid colors to Cubism's clashing planes. Cartier-Bresson would have been the first to scoff at anyone who calls him the capitalist oppressor. But then art is caught up in markets, too.

AIPAD held its fair the third weekend in May 2022. Sam Contis ran at Klaus von Nichtssagend through June 18, 2008, and "Time Management Techniques" at The Whitney Museum of American Art through January 8, 2023. Related reviews look at the May 2022 New York art fairs and the 2018 Photography Show.