Which New York?

John Haberin New York City

Edward Hopper's New York and Paul Cadmus

Edward Hopper lived in New York for nearly fifty years, much of it in the creative heart of the city—Greenwich Village, on the north side of Washington Square. It was, he said, "the American city that I know best and like most."

But which New York? He had many from which to choose, no small part of an ever-changing city's appeal, and Hopper captured them all. That scope alone could account for the power of his work. It leaves his art in transition, like New York itself, between the acts in a theater, between solitude and human connections, or between day and night. That very uncertainty has made his scenes so iconic, and the Whitney Museum brings them together as "Edward Hopper's New York."  Nearly a decade after the Whitney's look at Hopper drawing, it amounts to a retrospective all by itself. It might also be a refusal to settle for anyone else's version of the city.

Nearly a decade after the Whitney's look at Hopper drawing, it amounts to a retrospective all by itself. It might also be a refusal to settle for anyone else's version of the city.

Ask an artist or two about their work, and you can almost hear the gears turning. Where to begin? It is unlikely to be where Paul Cadmus began an interview, with the old masters. He rattles off an eclectic and eccentric mix, with little in common but the impossible—the search for timelessness and pleasure. One and all, they root that search, too, in the human body. Who knows where the search would end and in which New York?

That interview plays on video amid a show of his male nudes, mostly drawings. As a hasty addition, he says that he hopes nonetheless to contribute something original. That extra something could be the frenetic detail of his drawings and the unapologetic expression of his desires. Others, like Hopper, roamed the streets of Manhattan and gazed at its bridges. Still others looked to a world of dreams or to modern art itself. It may be impossible to say whether Cadmus starts by looking within or without.

Beyond the landmarks

Edward Hopper makes a point of refusal. Asked in an interview whether he had loneliness in mind when he painted, he refused to say. Reticence appears, too, in my opening quote from text accompanying the exhibition. Is it even a compliment? Would he just as soon have stayed in Paris after 1908, if only he had the money and better French? Did he know New York City best because he could not bear to leave it, or did he like it only because he knew it so well?

He grew up in Nyack, on the northern edge of suburbia, and family trips helped acquaint him with the city. He got to know it better as a student and commuter, and he settled in for good after a trip to Paris. A budding artist had to make it to Europe, and his endless curiosity took him there as well, but Cubism and Modernism were just coming together, and Hopper would have to discover them back in New York. Many another American never did, and that, too, says a great deal about his vision. Call it realism if you like, and he found work as an illustrator, but it is never conservative. One might look to the origin of his restaurants and river views in bistros along the Seine.

Still, they are New York restaurants and rivers. He lived through many changes from his birth in 1882 to his death in 1967, but his view of the city hardly budged. For him, a major change was to a larger apartment in the same building, with more space for his printing press and a better view of Washington Square. The curators, Kim Conaty with Melinda Lang, mix divisions by chronology, subject, and medium, and one can easily lose one's place. Where are we? For an answer, consider how much the city has meant to others.

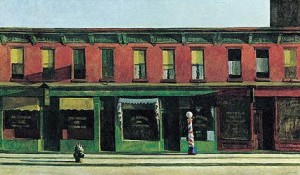

There is the city of landmarks, like the Chrysler Building or the Guggenheim Museum, and Hopper lived to see them rise. Drawings take him to the statue of William Shakespeare in Central Park, in brooding but luminous shadow. Still, he all but ignores the skyline, and he goes so far in one study as to edit out the Brooklyn Bridge. The Whitney devotes a section instead to "The Horizontal City," with rows of apartment houses and the length of quite another East River bridge. He preferred his rooftop or an elevated train for the view across the city or looking down. In his best-known painting, Early Sunday Morning from 1930, the shadows of a hydrant and barber pole accentuate its breadth.

Landmarks are not just for tourists, but real New Yorkers prefer its neighborhoods, and Hopper, too, had a preference for the everyday. From the moment he descends from the roof, he is on his feet, from the Manhattan Bridge to Harlem, like Winold Reiss in search of modernity. Still, he combines scenes freely, picking and choosing from its water towers and architecture, like Bernd and Hilla Becher in later photography. A two-story house stands implausibly apart, as the only element of the skyline in Skyline Near Washington Square. A brownstone on Central Park West is both apart from and inseparable from the seemingly wild greenery. People often come as finishing touches, not in sketches but in a finished painting.

There is also the city of art, and a short walk would have taken Hopper along Eighth Street, where Alfred Stieglitz had his gallery and, later, the Whitney its first home. Certainly Hopper kept up with art, and he had a special fondness for theater. The exhibition has a section for just that, including the elaborate Sheridan movie house in the Village and chorus girls on Broadway. Still he never once shows a museum or quotes a work of art, and his theaters lie perilously empty, their stage curtains closed. He leaves a woman alone in a balcony and a couple alone taking the first row. The darkness of house seats may extend to the orchestra pit as well.

A city in transition

What, then, of a more discomforting city? Early twentieth-century New York can easily mean the Ashcan school, which had its own dark river views. Still, it sought the action, like George Bellows in a boxing ring, not Hopper's unearthly quiet.  It also saw a darker, filthier city, far from his radiant light. His crisp, bright planes and the deep blue of his New York waters will not appear again until postwar art, but by then Hopper was looking back. He wrote Robert Moses, who gave New York its public housing and expressways, to complain about development around Washington Square by New York University.

It also saw a darker, filthier city, far from his radiant light. His crisp, bright planes and the deep blue of his New York waters will not appear again until postwar art, but by then Hopper was looking back. He wrote Robert Moses, who gave New York its public housing and expressways, to complain about development around Washington Square by New York University.

Could that leave a different kind of discomfort? For many, a city will always embody anonymity and isolation, and they will find them in Hopper's late-night diners and sunlit apartments, the occupants exposed and alone. He returned often, too, to inhospitable places, like the Macomb's Dam Bridge at 155th Street and Blackwell's Island. Before it became Governor's Island, with comfortable apartments, it held only a smallpox hospitable and an asylum. The show opens with Approaching the City from 1946—faceless houses on the far side of railroad tracks and a concrete wall. At Hopper's death, Brutalist architecture was in progress, including the former Whitney Museum on Madison Avenue by Marcel Breuer, but he got there first.

Still, this is a sunlit or moonlit world, of uncanny brightness and everyday lives. What else could make Hopper so popular? He loved light and loved exploring, no matter what he found. He felt at home with the people he painted, even as they could never be at home with themselves. His wife, Jo, served as model for three people in a single painting. She made the perfect companion, too, as actress, artist, and reader, not to mention wry commenter on him and his work.

In that late interview, he changed the subject from loneliness to light—especially, he hastened to add, daylight. That may sound odd given so many night scenes and darkened theaters. Yet his late work grows larger and brighter, which only adds to its strangeness. From the start, though, he knew the limits of artificial light. Shop windows could darken after hours, and only once does he glimpse a movie screen. Leave it to Andy Warhol to linger over the Empire State Building at night.

Could Hopper's insight, then, lie in so many temptations and refusals? They produce, as the Whitney says, "awkward collisions of new and old, civic and residential, public and private"—although I am not so sure about the awkward. Rather than collisions, too, one might think of unending transitions, in a theater at intermission, a bridge in the afternoon, or early Sunday morning. The entire night serves as a moment of transition for a woman in an automat or a couple clinging together on a train. It must have served that way, too, for an artist acquainted with the night. He could have said, like Robert Frost, "I have outwalked the farthest city light."

Moments of transition rely, too, on shifting points of view. A woman, clothed on her bed or standing nude, looks out a sunlight window, while others unseen or the artist behind her looks in. In Tables for Ladies from 1930, a couple (not ladies) at table, a woman checking appointments, and a woman adjusting a lavish display of food all have their purposes and points of view. Hopper slides easily, too, among the glances in a theater, an office, and a cafeteria. He took to the rooftops or to elevated train windows for still more. He leaves it to viewers to find their own.

Old masters at the Y

Where to begin indeed? For Paul Cadmus, the list of influences begins with Luca Signorelli, whose early Renaissance precision fed the sinuous outlines of his standing nudes, and the fleshier women of Peter Paul Rubens. It extends to the Rococo wildness and weightlessness of François Boucher. Along the way it has time for the undisguised and disturbing eroticism of Caravaggio before his subjects turned to pain and death. When Cadmus draws a man lying in bed, he, too, can offer temptations but only scant comfort. In the changing room at the Y in 1933, from an artist just short of thirty, or a Subway Symphony from the 1970s, men are literally climbing the walls.

That Y.M.C.A. Locker Room has no lockers, only partitions that open onto still more men. The subway, too, not in the show, has an unnaturally wide aisle in unnatural perspective, but not wide enough for the behavior of crowds. In the drawings, a man lies on a stone like a dead Christ, while those in bed lie on their backs as well. They look just as restless awake or asleep. Standing or seated men lean forward, curling into themselves. It is more a sign of agony than introspection.

They are at once inviting the male gaze while turning away. They have the lean, muscular bodies of the Renaissance but a refusal of Renaissance idealism. Right on the way in, one has thick calves and thighs, but preposterously narrow knees and ankles. Cadmus does not name an influence from the late Renaissance, but for him its Mannerism began earlier and persists to this day. Is this magic realism truly magic or realism? He himself would say so, but do not be too sure.

The question always hovered over prewar American art, and the Whitney called its look at American Surrealism in 2011 "Real/Surreal." One could see Cadmus alongside Philip Evergood, Peter Bloom, and Jared French. They, like George Tooker and Edith Gregor Halpert, struggled with social realism and their nightmares alike. Realism took them Coney Island and men on shore leave, but also to the desires they found there. Meanwhile Bellows has entered history for his love-hate relationship with bulked-up boxers.

Whatever you call it, it could seem hopelessly out of touch. Is starting with the old masters, like Cecily Brown and Kehinde Wiley, unlikely today or merely pretentious? At the height of Modernism, it could seem a refusal to face reality. It does, though, face a contemporary issue head on, sex. In another painting, Cadmus takes his troubled relationship with a man to the beach, along with his lover's new wife.

He is also in love with technique. Paintings stick to an early Renaissance medium, tempera. Drawings have a dense crosshatch in crayon. A man's blanket has discordant colors on each side, but most stick to black with equally dense highlights in white. I may still look down on his art and his confused desires, even while admiring them. But then he must have felt the same way.

"Edward Hopper's New York" ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through March 5, 2023, Paul Cadmus at D. C. Moore through March 16, 2024. Related reviews look at Hopper drawings and magic realism.