Learning to Love Commodities

John Haberin New York City

Nobody in the art schools ever told us that the decorative aspect should be the basis of all plastic art. Is it not the Salons that have created this absurd distinction between "the picture" and "the decorative panel"? Doesn't painting primarily consist in using color and design to decorate a surface?

—Paul Gauguin

Bauhaus: Workshops for Modernity

Bauhaus in America

When Clement Greenberg opposed abstraction to kitsch, he did more than declare the importance of painting, Modernism, or American art. He also redefined the art object. The more painting revealed itself as an object, the more it claimed to rise above consumerism. Even when Pop Art embraced advertising cartoons, and the movies, it still made painting, and it still made art. Now that anything could be art, what else could it make?

Before all that, however, Modernism had no problem making commodities. Bauhaus and other movements incorporated design, and they positively demanded knockoffs. After all, they were teaching the world how to design. In the process, they were teaching it how to live.

Bauhaus means "house of building," but what was the Bauhaus building? It was not, at least at first, new architecture and new cities. Those hopes came only later. When Walter Gropius merged the Grand Ducal School of Arts and Crafts and the Weimar Academy of Fine Art in 1919, he created a school of art and design. It became so much more.

Love, wrote Richard Wilbur, calls us to the things of this world. So, as it happens, does a really good shopping experience. The Museum of Modern Art asks how the Bauhaus supplied "workshops for modernity." In the process, it shows tensions within modern art between politics and purity. And with a show of Josef Albers and László Moholy-Nagy just three years before, the Whitney asks how Bauhaus came to America.

Taking Modernism to school

One remembers grander ambitions, and they are there every step of the way. The history of the Bauhaus mirrors the very history of Weimar Germany. They rose and fell together. Like the nation's first republic, the Bauhaus began in Weimar after World War I, and the Nazis shut it in 1933. Plagued by suspicion and lost funding, it fled twice—to Dessau and then to the Nazis' own capital, Berlin. It flirted with German folk traditions, left-wing politics, propaganda in art, and consumerism in the industrial age.

It had its successes as a school, an ideal, and even a business. Marcel Breuer created its best-sellers with his stacked tables and tube chairs, not to mention the future Whitney and then the Met Breuer and Frick Madison, but anyone will recognize its furniture, sans serif typefaces, and posters as part of life. I walked through a retrospective crammed with four hundred items the day after Thanksgiving, when I should have been shopping. The school mirrored the republic in its financial collapse, too. During Weimer's runaway inflation, Herbert Bayer at Bauhaus even designed bank notes, with colors for date of issue rather than face value. Artists struggling today to make money could learn something.

However, a MoMA retrospective is a history of modern art, too. It may sound foolish to identify the Bauhaus with Modernism, although Gerrit Rietveld pursued it into de Stijl and Ettore Sottsass played against it. At the very least, it sounds like a narrow version of Modernism, as the march of progress, as with a "good design kit" for the Museum of Modern Art. That version has taken its hits for forty years now, and think of all that the Bauhaus leaves out, critical theory aside. This is Modernism in one country. It is German art without even German Expressionism.

But the Bauhaus had so much more. And that is how it came to stand for the transformation of modern life. It had global ambitions from the beginning, and it drew on every school of modern art. Lyonel Feininger slims down Cubism and Paul Klee supplies Surrealism, with his early paintings and with dark and funny puppets for his child. So does László Moholy-Nagy with ghostly photograms, or the direct imprint of objects on photosensitive paper. Wassily Kandinsky came all the way from Russia—to speak for another revolution and, in Kandinsky's late work, for abstract art.

The school's evolution tracks modern art as well. It had its roots in the craft movements, and it sought at first a universal vocabulary in art of the past. Lothar Schreyer uses a conjunction of flat and primitive forms for a woman's coffin. Gerhard Marcks updates folk art with woodcuts and a small altar for private devotion, and a student, Gyula Pap, designs a menorah. Rudolf Lutz sketches the Isenheim Altarpiece, the shattering High Renaissance painting by Matthias Grünewald. His teacher, Jonannes Itten, turned out quaintly decorative takes on Cubism.

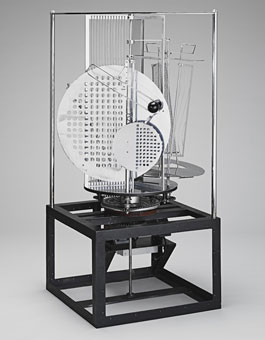

Schreyer and Itten quickly left, and art history has pretty much left them behind. Their departure only accelerated the drive to bridge past and future. Gropius designed a totally abstract war monument, like a Cubist sculpture by Raymond Duchamp-Villon. It did not lead to outrage, like the Vietnam War Memorial by Maya Lin, but Germany did not exactly fall in love either. Still, slowly tradition gave way to technology. For his Pillar with Cosmic Visions, Theobald Emil Müller-Hummel, starts with a World War I propeller blade, and Moholy-Nagy soon tosses aside cosmic visions for mechanical ones with his metal sculpture.

Homage to the affordable

Gropius already worked on housing, but his successor in 1927 wanted more. Hannes Meyer placed design in the service of cities affordable to all. After Meyer's dismissal for leftist leanings, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe presided until the end. He reinstated separate disciplines, with the idea of perfecting each in its area of expertise. That, too, is part of Modernism, and its formalism triumphed after World War II. Mies, Moholy-Nagy, and Josef Albers brought just that version of the Bauhaus to America.

The story sounds linear, but do not expect straight lines. Mies did not impose capitalism on Meyer's communism. Multidisciplinary products were there all along. Bayer's proposal for a "multimedia building" combines architecture, a marquee for advertising, and the movies. Give me a Breuer chair anytime. Give me, too, a school that sought to democratize the making of art rather than certify aspiring MFAs as star emerging artists.

Bauhaus encompassed so much of both Germany and modern art, including the tensions within. A painting of the Bauhaus stairwell by Oskar Schlemmer hung in a stairway before MoMA's 2003 expansion. Its dry style and literal placement stood for Modernism's dogmas and prejudices. Feminists will note that women appear at Bauhaus mostly as students. Marianne Brandt designs metal and glass lighting fixtures, but Gunta Stölzl, Benita Koch-Otte, and Anni Albers all leave tapestries. You decide whether to call the attention to "lesser" art forms a rediscovery or an insult.

"Bauhaus: Workshops for Modernity" has too many students and too much work. One really does march through it like a mall. How many shopping days until Christmas? Yet that, too, has its upside. It gives a more complete picture of the Bauhaus, and it stresses the relationship between art and teaching. As Rosalind Krauss said about Auguste Rodin, one has to rethink modern art as about reproducibility, too, not just the "originality of the avant-garde." And the difference between students and teachers says something as well.

"Bauhaus: Workshops for Modernity" has too many students and too much work. One really does march through it like a mall. How many shopping days until Christmas? Yet that, too, has its upside. It gives a more complete picture of the Bauhaus, and it stresses the relationship between art and teaching. As Rosalind Krauss said about Auguste Rodin, one has to rethink modern art as about reproducibility, too, not just the "originality of the avant-garde." And the difference between students and teachers says something as well.

Could the need to teach have prompted the search for universals? And could that search have pushed Modernism in a direction that no one expected? Surrounded by charts and color wheels, Klee evolves from his Twittering Machine to the grid. Even so, his grids have the soft light of morning and evening. Student work looks routine by comparison. It says something that Albers and Bayer, the advocates of pure form, began as students and ended as teachers.

It says something, too, that Albers found his most austere forms in New York City. His first grids, in glass and wire, still have the glow of stained glass and an attention to materials. Yes, the Bauhaus shines when form follows function, as in Josef Hartwig's chess set—with the shapes derived in part from how the pieces move. It shines even more, though, with the best artists at their maddest and most interdisciplinary. Kandinsky is more concerned for stage sets than in his Guggenheim retrospective. With his abstract painting, scrap-metal sculpture, photograms, and portrait photography, Moholy-Nagy offers not just the Bauhaus and Bauhaus photography all by himself, but the contradictions and experiments of modern art.

From Bauhaus to our house

The Bauhaus was out to change the world, but Albers and Moholy-Nagy settled for teaching art in America. They did it with a reformer's zeal, too—and an insistence that, when it came to the twentieth century, America had a lot to learn. The Whitney takes them from their Bauhaus years in Germany, in the 1920s, to their adopted nation. And they as much as their students come off as slow learners. Thankfully, they never stopped teaching and learning.

Gropius united art and design, and America had lots to learn about both. The Bauhaus put the modernist imagination, as free of history as of surface decoration, at the service of industry and craft. The Whitney includes both craft and publications, many of which Moholy-Nagy might have edited. It contains media from porcelain enamel on steel to Formica and Bakelite, the plastic used for radios as recently as in an Elvis Costello song. However, both Albers and Moholy-Nagy found themselves more at home with artistic experiment for its own sake, especially when they could claim to codify its rules.

Kandinsky and Klee passed through the Bauhaus, too, but Moholy-Nagy preferred the look of Russian Constructivism to a Kandinsky Composition. His paintings share its planes floating in a pale field. His kinetic sculpture, sometimes with its shadows projected on a wall, owe something to its stage sets and to its faith in a world in motion. Dada had introduced kinetic sculpture, too, and Moholy-Nagy made photograms around the time of Man Ray in Paris. He seems eager to preserve the essences of the modern world, as in his photographs of cities. Perhaps that explains why, for all its hyperactivity, his images can look at once static and cluttered.

Albers has a still more determined sense of artistic purity, and he made it his educational mission as well. If his early work gives colored glass a tight grid, it might be instructing fin-de-siècle Vienna in Piet Mondrian. Of course, one knows him best for Homage to the Square, late paintings of concentric, off-center squares, and when I find myself wishing they came sooner, I know a show is in trouble. Along the way he taught at Black Mountain, alongside such freer spirits as John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg, and at Yale, which still looks good on an emerging artist's CV. One could see his pedagogical style in a whole show a few years ago at Hunter, devoted to grids in shades of red. It startles me to recall that he had entered his twenties by the birth of Cubism.

The Whitney has taken an unexpected direction for a museum of American art. With "The American Effect" in 2003, it exhibited contemporary "global perspectives on the United States." The 2006 Biennial included artists born or based overseas. Another exhibition catalogued Picasso's heavy hand on American art history, and this one began at the Tate. See a pattern? If New York once "stole the idea of the avant-garde," as a famous critique has it, apparently Europe now claims copyright infringement.

As with the Picasso show, one has fun comparing personalities, but also too much pedantry—in this case, with two notable pedants. Moholy-Nagy and Albers had very different styles, little interaction in Germany, and even less in this country. The first settled in Chicago, where he directed what he called Bauhaus for its last year before helping to start what is today the Institute of Design at Illinois Tech. I could imagine a show with more excitement and more of the mark on American artists, not to mention more of Bauhaus. Mies's Seagram Building still looks gorgeous in New York and still looms over the history and practice of architecture. Perhaps the show's real value is in tracing the very idea of a school, from a modernist movement, through pedantry at its loopiest, to university credentials in art today.

"Bauhaus: Workshops for Modernity" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through January 25, 2010. "Albers and Moholy-Nagy: From the Bauhaus to the New World" ran at the The Whitney Museum of American Art through January 21, 2007.