Faking History

John Haberin New York City

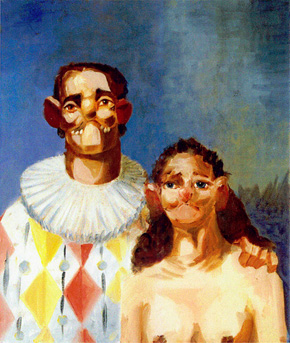

Cecily Brown and George Condo

Cecily Brown should have learned her lesson. She has been staring at her reflection in a mirror for thirty years now and seeing only a temptress, a crone, a death mask, or a skull. She cannot help looking, though, for she is only human. Besides, she is a woman and an artist, and this is a savvy woman's art. It should have you looking, too, at the Met, but you will not see anything as dreadful as death. This is painting so lush that it keeps coming back to life.

Vanity, vanity, all is vanity and a striving after fame and fortune in art. Brown came to New York in the 1990s, with the much hyped Britpack (or Young British Artists), only she chose to stay. I caught her in 2000 as an emerging New York artist at MoMA PS1 (then just P.S.1), again with a growing approach to Abstract Expressionism, and in 2020 with her aspirations to the Old Masters. In between she brought her torments and seductions to the Drawing Center.  (I cannot repeat all that here, so by all means follow the links for more.) As a postscript, George Condo, too, takes pride in faking history, at the Morgan Library, but with a greater Postmodernism and a great deal less thought.

(I cannot repeat all that here, so by all means follow the links for more.) As a postscript, George Condo, too, takes pride in faking history, at the Morgan Library, but with a greater Postmodernism and a great deal less thought.

Vanity, vanity

Surely Cecily Brown is due for a retrospective, and surely she is the last person to need one. The Met keeps its aspirations modest, in the long central room of its wing for modern art. It can handle just fifty works, about half of them preliminary sketches, but it can make almost anything look like a blockbuster. It does not need a monster of a mural that dominates, for now, the lobby of the Brooklyn Museum with its elusive subject matter and lavish red. It does not even need much in the way of Brown's development as an artist. She began with lighter backgrounds and sketchier subjects, adding denser subjects and more colorful brushwork, and finally veering toward monochrome, but she is still a woman staring at her reflection while daring you to stare at both.

What you see may depend on you. Will you find the corpse in Blood Water Fruit Corpse—and is that paint blood and water or the thing itself? Will you find corpses everywhere else? Or are they even corpses, for white spirits rising and pink flesh in ambiguous poses close to the floor could be very much alive? You may need a hint to spot a cat hiding under a table, but it has no fear of death. And yet Brown's titles allude to a long tradition of fearing death in life.

Vanitas long attached to a woman at her mirror, for youth will fade, and fruit are still life—in French dead nature, or nature morte, like Brown's Lobster, Oysters, Cherries, Pearls. Skulls are momento mori, or remember death. Hers arise as if of their own accord from girls in frilling dresses, for the skull's eyes and nose, and an arch, for its top. (A smaller scene serves as its mouth.) Rooms for still life have the grandeur and luxury of aristocratic Europe, with other reminders of the past on its walls. A table spread for a picnic could be a banquet or a mad tea party, awaiting Brown in her madness or you.

The show's title, "Death and the Maid," positions her as forever between life and death, old and young. So does a brushy painting called BFF. The term is up-to-date, but paint itself (an older artist advised her) will always be her best friend. And that could be her real theme, for all the heavy titles. Still life can morph into interiors, into bodies in an unstated narrative, or abstraction. Painting is like that these days, shifting among genres, but she was among the first in making it so.

The overtones do get in the way, much as for many artists today working between myth and abstraction. Death and the Maid alludes to Death and the Maiden, the maid bringing flowers in Olympia by Edouard Manet, and (gulp) a woman's role in the workplace today. A shipwreck with no visible ship may allude, tenuously, to Théodore Géricault—and Willem de Kooning and his women hang over them all. Another still life is after Frans Syders, the Flemish painter, because what still life is not? One might do better to treasure the ambiguity and forget the details. Or treasure a world well lost and the paint.

For all the moralizing, Brown traffics in pleasure, like Talia Levitt in rags. When she riffs on The Battle Between Carnival and Lent, by Pieter Bruegel, she has not made up her mind. The picnic table has an ashtray, because she has any number of bad habits, and she is in no hurry to give them up. But then neither was Snyders. The freshness of this world accounts for his appeal, too. Brown's art may lie first and foremost in seeing through the excuses to make art.

Never mind

When George Condo speaks of work from the 1990s as "fake Old Masters," he is kidding, of course, but not by much. A pair of hands really is a fake, but a very good fake, about as close to classic images as a contemporary artist will ever get, give or take the rough edges. One might say much the same about his entire career, a veritable art of fakery. He calls his drawings an "architecture of the mind," but that may prove a fake as well. No artist is more averse to deep thoughts.  Now One might have entered his mind or the collective consciousness of a shallow culture.

Now One might have entered his mind or the collective consciousness of a shallow culture.

NOW in his mid-sixties and already the subject of a New Museum retrospective back in 2010, Condo opens with a drawing from not yet twenty, Entrance to My Mind, but try not to get your hopes up. You may not get past the entrance. This is architecture, drawn in red chalk as skillfully as those hands, but of what? You might make out a building (perhaps a condo), a presiding figure, or nothing at all. He is just finding his way himself, but already he knows how little he wants you to know. He has been looking for someone to hide behind ever since.

The hands never quite quote praying hands by Albrecht Dürer, but then Condo has hardly a prayer, not if that requires a believer. He returns often to Pablo Picasso, especially those women crying out in pain from the late 1930s. Sterner critics have dismissed late Picasso as glib and accessible after Cubism's intricate deceit, but Condo might take that as a compliment. He has called his own work "psychological Cubism," but this is not depth psychology. One sheet manages to hide behind three artists at once, as Picasso morphs into Woman I by Willem de Kooning and Goofy out of Looney Tunes, and somehow it makes sense. Guess whose face wins out?

The mind has its demons, and demons need a place to hide, too. They peek out from behind seated women, as eager to catch your eye as the women are to pose for an Old Master. Their coarse shapes spill out into the women's dark hair. Another woman is a French maid, while a man is a smiling sailor, and you know what kind of sex they like. By 2003 they share Condo's mind with two recurring figures in bow ties, Jean-Louis and Rodrigo, before Kooning's yellow and Looney Tunes return. The mind reels.

Entrance to My Mind lends its title to a show of just twenty-eight drawings, all recent gifts to the Morgan. It signals the museum's still newfound commitment to contemporary art, much like the Met's ill-fated expansion to the Met Breuer. Just as much, it signals a commitment to one artist that I myself could live without. The Morgan counts Rembrandt among his ancestors, along with Francisco de Goya and his graphic imagination, but they are not so easy to find. Condo himself based a drawing of Rodrigo on Giorgio de Chirico, and that is not so obvious either. Somehow de Chirico's magic realism has lost its magic.

That is not altogether a bad thing. Condo belongs to a postmodern generation that never believed in magic. Critics were quick to question the originality of the avant-garde as well, as were artists as penetrating as Philip Guston and as glib as David Hockney. Condo anticipates art's madcap mix in the present, too. Down in Tribeca, Katherine Bernhardt applies her biting color and formidable brushwork to Bart Simpson. I cannot swear that she justifies her choice either.

Condo adopts French and Italian for his alter egos and their cheap laughs deliberately. Jean-Louis and Rodrigo are stock figures in his take on an old comedy, much as Claude Gillot in the Enlightenment, also at the Morgan, prized the commedia del'arte. Speak of the mind all you like, but this is theater, and Condo has designed costumes for ballet. He has his virtuosity and respect as well. A woman in pearls in pale blue translates the vertical division in a Picasso face into a very human shadow, much as Picasso translated shadow into a painterly and psychological division. Modernism's daughters still have their seduction.

Cecily Brown ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through December 3, 2023, George Condo at The Morgan Library through May 14. Related reviews track both artists more than once over the years, with links in the text.