Wide Aisles and Tight Spaces

John Haberin New York City

Kaari Upson and Omar Fast

Janet Biggs and Regina José Galindo

Kaari Upson spends way too much time shopping—and, she wants you to know, so do you. She is also fiendishly attached to what she finds.

It takes her into tight spaces and dangerous territory, but then new media are supposed to do that. Yet the same media are also used to numb the senses and to sell you something, and she plays on that as well. So does Omar Fast, who seems bent at once on selling you cheap goods and keeping you out. It is hard to say which is more morbid, his videos or the storefront in which he exhibits them. Janet Biggs is back on dangerous grounds as well. She and Regina José Galindo use confining spaces as metaphors for political violence, but their lush settings and direct human encounters also point to hope.

Shopping spree

Waif-like, with short blond hair, Kaari Upson sprawls on cartons of Pepsi, stacked like a supremely uncomfortable throne. She might have been wearing that plaid work shirt and those jeans for days now or even years. She might have been wearing them when she sculpted soda cans for the High Line in 2015. She might have been wearing them, too, when she arranged furniture like flayed skin for the 2017 Whitney Biennial. Maybe they provide the comfort of familiarity. Maybe they make up for the failed promise of her show's title, "Good Thing You Are Not Alone."

She dresses, she explains, as her mother, and her mother's felt presence could provide a greater bond and a greater comfort or leave her still further alone. My mother never dressed like that or drank Pepsi, but then boomers and Gen-Xers are now mothers, too. She also dragged me on her weekend shopping tours through department stores, which terrified me—but never to Costco, where the soda resides. Upson is alone there on another video as well, driving her cart through its wide aisles. She could almost be stocking the shelves rather than shopping, as if too attached to them to see them empty. Sure enough, she stocks them in quite another way off video, in dozens of stuffed replicas piled at the New Museum.

Their materials include cat hair, Complete Idiot's Guides, and pages from Artforum—only reasonable for an artist with attachment and achievement issues. The limp bodies look almost tragic, but the shelves invite one in to find still more video channels. In one, Upson drags a sofa through a watery landscape, the close-up making it all the more unintelligible. She is determined one day, like luxury goods for Lauren Greenfield, to drag the purchase home. If she does, she will find more soda cans in a second room, hundreds of them, cast in aluminum from the real thing. She will also find the inscrutable objects that rest on top of them, like twenty-first century fossils.

She may not make it home all at once, for another video has her checking out Las Vegas real estate, as In Search of the Perfect Double. There, too, she takes her lost original seriously, comparing home after home to it and finding them wanting. (Oh, for goodness sake, Formica!) Maybe she is addressing a human lost original as well—or her mother. Of course, taking the job seriously means crawling into absurd places, as if to replicate once more the stuffed bodies. She identifies the potential home buyer only as her.

The walls surrounding the aluminum cans contain more inscrutable sculpture, in foam shaped like sagging curtains or unmade beds. One bears the teeth marks of, she swears, her mother. Another bears the title Who's Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue after Barnett Newman, for yet another kind of doubling. But then the very look of bedding splattered with paint goes back to a combine painting by Robert Rauschenberg—and "Wall Hangings" to women like Sheila Hicks. Another video closes in on Upson's eye, split in two by a mirror, for a further equation of looking with doubling and of mothers with mirrors. The mirror's touch brings tears.

The death of the originality of the avant-garde sounded downright liberating for critics like Walter Benjamin or Postmodernism, but here it takes on personal significance. Upson drives the point home in large drawings right off the elevator—as always, with repetition and overkill. More images of herself spill over one another, surrounded by words directed at herself or you. They speak of mediated and medicated experience, the endless reproduction of the self, guilt, and the difficulty of love. Their skilled realism in graphite, ink, and gesso helps to moderate the diatribe, as does their reflection of the video and sculpture. When all else fails, she can always go shopping.

A Marriage of convenience

Omar Fast makes sure his videos are hard to follow. In fact, he makes it hard to know that video is even there. Even if you have memorized the address and visited many times before, you may hesitate to enter. Fast has restored a busy corner of the Lower East Side to its previous state, as a mysterious business hidden behind a small convenience store. His gallery might have fallen off the earth or never come to be. Its sign is gone, apart from Chinese characters, and so is much in the way of space for a show.

Consider it a marriage of convenience between the fringes of Chinatown and of art. The resemblance to its past life is uncanny, earning him the anger of the Chinese American community for its "poverty porn"—right down to a glass counter for a token selection of cheap electronics and two ATMs, neither of which works. A monitor of the sort for bus schedules runs to no obvious purpose, not even to keep the shop's owner halfway awake. The artist has redoubled the trickery, with the illusion of the illusion of an independent business apart from whatever lies behind a black curtain. He also redoubles the difficulty of his video, which plays continuously on that monitor. If you ever felt lost owing to walking into new media that were already running, here you have to dare yourself to walk in at all.

Fast's videos are always hard to follow. In fact, they are so hard to follow that I can seriously question whether they are political art. That is quite a trick, given such past subjects as a suicide bombing, the interrogation of political refugees, and the generational consequences of the Nazi occupation. He combines deep focus and full color with shallow spaces and plenty of black. He also brings arbitrary cuts in time to the conventions of documentary realism—and documentary realism to the quandaries of the mind. A voice-over may explain the action without quite describing it, and the characters on screen may seem to have lost their voice.

Here the video dates from several years back, when the space might have held that very convenience store. It seems to be about a funeral, perhaps of someone you know. The voice-over describes not so much a particular funeral as the business, in lurid detail, but children flit in and out to make the loss theirs. Is it a matter of politics, real estate, business as usual, or life and death? The installation dances around much the same question. Is Fast dealing with gentrification, the fate of galleries and museum expansions, both or nothing at all?

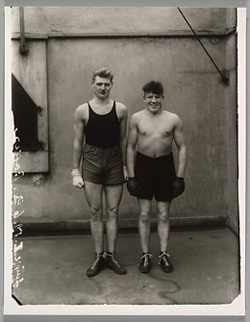

He is so infuriating because he is always holding out the urgency of politics and human lives—and never quite getting around to either one. He shares the puzzles of another politically inclined video artist, Artur Zmijewski, but in closer to a dream state. And here he gets dreamier still but just as morbid in a new video, in the back room. Something lies behind the curtain after all, only not the old neighborhood. August sounds like summer winding down and with it a greater optimism, but here it names a photographer. Where August Sander saw the Germany he knew as a catalog of human archetypes, Fast makes Sander one himself.

He shows the photographer at work in a wider landscape than the finished photographs ever show. The sitters look a little stiff but young and alive, and so does Sander. And Fast frames them with Sander as an older man, hardly able to raise his head from the ground. Further cuts add still another angle, something to do after all with Nazis and what they thought of his work. Politics and art could not get more urgent than that, not least since Sander lost his son to the Nazis, but once again the video stops frustratingly short of their encounter. When the show ends, though, you may still feel haunted by what the gallery has swept away.

To extremes

Janet Biggs and Regina José Galindo are not making documentaries. Their videos stop just short of horrific violence, and the barriers that appear are of their own making. They do not flinch at real-world terrors all the same. Both go to the Third World and to dangerous extremes, and their subjects know the dangers as a way of life. Biggs opens with a forbidding landscape in the Horn of Africa, Galindo with a verdant one in Guatemala. And both end with faces caught between a quiet dignity and fear.

Biggs has gone to extremes before, and the journey was personal. It took her through a mine shaft and into a laboratory, with her body and her mind the subject of experiment. Talk about depth psychology. Here she takes herself out of the picture. She titles the video Afar, as if to attest to its remote setting or the challenge of keeping it at a distance. It refers, though, to a nomadic people that face political barriers to their movements and to survival.

She opens with volcanic crags and the steam that they release into a dark sky. The scene shifts to stark but often gorgeous open territory, where salt traders and the camels that they use as pack animals carry the story forward with a slow but seemingly inexorable rhythm. They till harsh ground with the barest of tools and seek a rest in the company of one another and tobacco. Steel gates interrupt now and then with other men and women, white men and women, glimpsed from behind, as if unable to leave or to enter, or passing in front, like guards for unseen prisoners. In time a cello, scored by William Martina, adds its poignancy to the ambient sound,  but it must compete with the sound of those very people flinging themselves against the gates. The pulse is almost as unnerving as the image.

but it must compete with the sound of those very people flinging themselves against the gates. The pulse is almost as unnerving as the image.

Those westerners are dancers, the company of Elizabeth Streb, in a video with no easy triumphs and no simple victims. Biggs called her last show Can't Find My Way Home, and here the white dancers get no rest and the Africans have no home. By the end, the video returns to the crags and the volcanic activity within. It looks like cauldrons, with no miners or devils to tend to them. A young African appears on all three channels, from slightly different angles that add to the sense of unrest. And then the frames freeze on his uneasy glance.

Galindo ends with a close-up, too, but of herself rather than her implicit subject. One could almost call her 2013 video Regarding the Pain of Others, after Susan Sontag, but without Sontag's skepticism about getting past the satisfaction of looking down on suffering. Its real title, Tierra, identifies it instead with the land in the aftermath of a refugee crisis and mass murder. Viewers entering in the middle will see Galindo's naked body standing on a grassy knoll stained by soil and surrounded by a pit. Who put her there? No one, for it started as flat ground, before an earth mover began to dig.

It sets to work completing and deepening her isolation, with only the lighter skin of her breasts and belly as body armor. At times its shovel pauses just over her head, leaving one in hope of a respite and fearful for the threat—and then the rig shifts position, and the shoveling begins again. With the circle completed, it turns to narrowing her perch, while the trees behind her shake. Will it sweep her up or knock her over into the pit? Will it bury her alive or leave her with nowhere to go? The uncertainty becomes excruciating over the course of more than half an hour, and then you, too, will have to find your way home.

Kaari Upson ran at the New Museum through September 10, 2017, Omar Fast at James Cohan through October 29, and Janet Biggs and Regina José Galindo at Cristin Tierney through May 27. Related reviews have looked before at Janet Biggs, political violence, and "Immersive Cinema."