Poetry and Purity

John Haberin New York City

Dorothea Lange and August Sander

"Contemporary problems are reflected in their faces." The words, from a fellow photographer and one of her most fervent supporters, speak volumes for Dorothea Lange.

She depicted workers and the out of work, during and after the Depression. She could make them so memorable that they have become emblems of an era, even as she gives the illusion that each and every viewer has a direct personal connection to the individual. August Sander in turn did the opposite, starting a decade earlier: working in Germany, he looked for archetypes but found individuals. Yet he, too, defined a nation. Either could serve as a warning or a model for an artist's grand ideas and real achievement today.

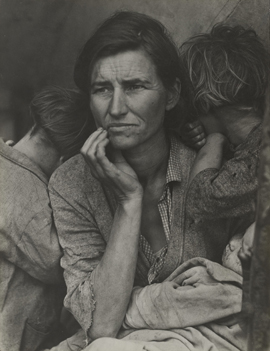

Lange could distill at once a person and an age. It has made her for many the very purist of photographers. Surely no words could convey what she could in a migrant mother's stern, sad eyes and wrinkled brow, parched by poverty and dust storms. Neither she nor the young children to either side could muster a word themselves. Still, those very words accompanied some of her earliest photos and helped put her on the map. Now at MoMA they demand all but equal attention, in "Words and Pictures."

In their faces and hands

Dorothea Lange was over forty when she encountered that mother in Nipomo, California, in San Luis Obispo county. Like Garry Winogrand and Diane Arbus after her, she began as a studio photographer but grew restless. But then America in 1939 could have made anyone restless—even someone far less politically committed. Just three years before, she had felt the need to descend from her studio, to encounter the face of the street. In the process, she invented a hybrid between photojournalism and portraiture that has shaped the medium ever since. Who needs text when faces like these can speak at once for themselves, their place in society, their country, and their times?

Even so, the street for Lange meant more than faces. Her breakthrough came in 1933, with an image that caught her off-guard as much as others. It shows a bread line in San Francesco, but as less a line than a dark mass. Backs turn from the camera in search of something more sustaining than art. Just one man does face the photographer, but unable to meet her eye, taking what pleasure he can in a cup of coffee. Winogrand's irony, with a woman turning from a space launch to photograph the photographer, seems a world away.

One remembers the huddled backs and his tired eyes as two tokens of anonymity and human need. One remembers, too, his hands clutching the coffee. Has he already made it to the head of the line and now can enjoy the warmth, or has he given up in despair? With the migrant mother, Lange again lingers over a telling face, but also a telling hand raised to the woman's chin. She lingers again, too, over backs—those of the woman's children, taking comfort in her shoulders. They have buried themselves so deeply that one may well remember only the woman, her hand, and her eyes.

Nor did Lange shy away from the possibilities of things. She had taken to the streets on May Day in 1934, where she found a ragtag march, but also a shortage of pride and hope. A man sinks into his knees, while his wheelbarrow lies overturned beside him. Her next major project, from 1937 to 1939, collects her vocabulary and drives it home. It has the face of California, but also Californians facing away—and no shortage of hands. A cotton picker the next year, fingers spread in felt tension, draws his hand to his mouth in fear.

Gestures would remain Lange's not so secret weapon. Appalled by the internment camps in World War II, she photographs a Japanese girl saluting the flag. The child's plea to her country speaks equally in her gaze upward, toward an unseen flag, and her hand across her heart. A later series pays tribute to a California public defender, but even more to his defendants and, again, their hands. One takes the oath to bear witness, while another has fallen to the table after the verdict. It speaks for the man's innocence, even as it speaks to his guilt before the law.

Lange becomes more hopeful all the same, if only a little, because her country does. And its hope lies in the growing inclusion of faces, gestures, and voices—plus a growing opportunity to stand apart. She already titled a book American Exodus in 1939, but was postwar America the promised land? In late work, gnarled fingers have expanded into the gnarled trunk and branches of an emblem of dependability, an oak. This is a big country, a sign declares in block capitals and a boldface conclusion. Dont let the big men take it away from you.

The price of air

Were Lange's pictures, then, tied up in words all along? Her photos of text predate the "Pictures generation" by decades. One Nation Indivisible, another sign proclaims, beside a child at play. Her sensitivity and wit show, too, in migrants walking the long road to LA. A billboard, Next Time Try the Train, does not aim at them. In fact, it does not aim at anyone, for the highway is otherwise empty, as if Lee Friedlander in "America by Car" could not afford a car.

Lange was a perpetual collaborator, the better to harness words. Her radicalism drew attention from an agricultural economist, Paul Taylor—who accompanied her to May Day, married her, and supplied the text for American Exodus. It includes his field notes and interviews along the way. Other photographs have captions by Archibald MacLeish, the poet, as Land of the Free in 1938. Twelve Million Black Voices in 1941 gives Richard Wright's African American history from slavery through the Great Migration a human face in the present. She joined Edward Steichen and others in 1955 for The Family of Man, which helped photography enter high culture at the cost of a few platitudes.

She was collaborating, too, even apart from writers. She shared government funding during World War II with Ansel Adams. Along with Walker Evans in the Dust Bowl, she created a lasting image of the Depression. Nor did state and federal funding come about solely out of concern for the arts. They were forging a sense of the American people connected to an active government—and Lange, like Bruce Davidson, could see politics only through the people. Lange's Migrant Mother illustrated a defense of the Works Progress Administration.

The roughly one hundred photos draw entirely on the permanent collection, a renewed focus of MoMA's 2019 expansion—or of recent shows of Constantin Brancusi and Louise Bourgeois. They cover her well, because her association with the museum goes way back. She was planning a retrospective with its legendary curator of photography, John Szarkowski, at her death in 1965 at age seventy. The curators, Sarah Meister with River Bullock and Madeline Weisburg, show her expanding her focus to Mormon communities, Ireland, and more distant travel. Can they, though, show her so attached to words? She was hardly the first or last photographer to appear in books, with a forward, or in Life magazine.

Her photographs still speak volumes entirely by themselves. The cotton picker's hand seems larger and more angular than life, as if it had come to silence him from a higher authority or the depth of his psyche. The most haunting shot of the public defender excludes everything but his piercing eyes—and the migrant mother was of part Native American descent, but neither she nor Lange is saying. Robert Frank might have been thinking of them all when he called his own landmark project The Americans. Even Evans comes closer to conceptual art when he collects postcards and penny pictures. And even when it comes to words, Lange is capacious enough to include lovers and haters of immigration and the New Deal.

She wanted a nation large enough for them all, even as she wondered what it would take to achieve one. She found the sign about a big country at a gas-station sign in 1938, next to a pump for air—and the word AIR just above it embodies the nation's promise of wide-open spaces. Was the air for free or at least included with the price of gasoline? Lange did more than almost anyone to document a nation as contested ground, while empathizing with the contestants. Does she belong to a past and purer world, just as her photographs stick to black and white? Maybe, but then she could always leave color to the book and magazine design.

Archetypes and stereotypes

If you are going to reduce people to types, it helps to treat them with compassion. August Sander did—and all in the pursuit of the universal. His photographs have collectively become a group portrait of Germany over the course of more than two decades starting in 1910.  It has room for young and old, men and women, workers and the comfortable middle class. It shows how they defined themselves in the dress codes of their class, their occupation, and an older world. It evokes a way of life that was already vanishing, as an older order endured world war only to give way to a fragile republic.

It has room for young and old, men and women, workers and the comfortable middle class. It shows how they defined themselves in the dress codes of their class, their occupation, and an older world. It evokes a way of life that was already vanishing, as an older order endured world war only to give way to a fragile republic.

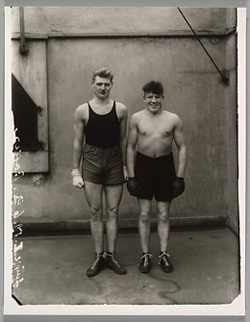

Yet he does see them as individuals, starting with the frontal poses that make them impossible to overlook. Sander does not seek Germany in the halls of power or the narratives of an older photography and an older art—although he did photograph a member of parliament and a political prisoner. His subjects smile or frown as they see fit, and even their inability to move appears as an act of compassion. It frees them from putting on a show, and it allows them something to call theirs, in their appearance and the house or shop front behind them. Photos also include paired and group portraits now and then, like a restless and stoic boxer as distinct versions of a shared way of life.

Compassion helps all the more after so many decades, when what Sander, like Teju Cole today, took for universals have become particular and quaint. Born in 1876, he began with the idea of "mankind in general" and its characteristics. He sorted people into archetypes as part of the whole, first in his native village of Westerwald and then in Cologne—many published as Face of Our Time in 1929. Now they appear on the Upper East Side in an ample selection reprinted by his son, Gunther. It was a project in sociopolitical economy, at a time when Marxism was in the air and sociology was being born. It also coincided with the rise of psychoanalysis, including Carl Jung and his archetypes.

In time, though, supposed archetypes become stereotypes. They become even more so in their titles. The types include distinctions recognizable from political and gender critique in the present—like "The Skilled Tradesman," "The Woman," "Classes and Professions," and "The City." Yet they also include "The Lost People," "The Sage," "The Philosopher," and "The Man of the Soil." What seemed scientific then borders on sentiment now. Maybe the search for archetypes always will.

The photos survive as more than stereotypes because of their imperfections. Sander insisted on "honesty" rather than the decisive moment, as the very requisite to a systematic view. He makes no effort to alter the dull or dour expressions. He embraces the stiff folds of peasant costumes, the boastfulness of a top hat, and the stains on a varnisher's apron. They make for more richly textured photographs and, like a video of Sanders at work by Omar Fast, a further reminder that their subjects are long gone. If one ever doubted the vulnerability of the Weimar Republic, one can see it again here.

It seems more vulnerable, too, in light of the compassion of photojournalists like Robert Capa—or "Small Trades" by Irving Penn, in his retrospective at the Met. Penn's photos dwell on broad gestures and the tools of the trade. Sander includes props far less often, and they remain subordinate to the archetype and individual. The varnisher holds a tin without showing off, while an alert hound stands in front of the man in the top hat as just another part of his boast. Where Penn makes portraiture an act of stagecraft, a masterful one at that, Sander makes it an act of remembrance.

Dorothea Lange ran at The Museum of Modern Art through September 19, 2020. August Sander ran at Hauser & Wirth through June 17, 2017, Irving Penn at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 30.