Her Calling Card

John Haberin New York City

Adrian Piper

About halfway through at MoMA, Adrian Piper leaves her calling card. Feel free to take one, but do not expect to stay in touch. The shortest version basically tells you to bug off. The longest one is worse.

"I regret," it ends, "any discomfort my presence is causing you, just as I am sure you regret the discomfort your racism is causing me." The regrets hardly sound genuine, but then what to believe is up to you, much like the choice of cards. The bug off consists of her assertion that she is quite happy alone in public, like many an urban walker—but is she, and can she ever be alone? Is she high-handed or honest, self-involved or self-aware? Is her art personal or political, and could she ever tear those poles apart? One thing for sure, it is always interesting and always her calling card.

Confrontation or retreat

With the three hundred works of "A Synthesis of Intuitions," Piper is exhaustive and exhausting, much like her text-laden mixed media and performance. For the first time, a retrospective snakes through the museum's entire sixth floor, plus the atrium, as curated by Christophe Cherix, the Hammer Museum's Connie Butler, and David Platzker. Has she earned it? I hesitate to say—and not just because she leaves so much undecided. She would be the first to tell critics that they got it wrong. She did so before in an open letter to Donald Kuspit, and she does so again with her often interactive art.

She places tables just outside the galleries, with a receptionist behind each one, waiting for you to check in or out of the show's midtown real estate. They ask you to sign one of three computer-assisted agreements, for her Probable Trust Registry. Never mind that she cannot trust you or you her. And the confrontations continue inside. She traps you into watching her on TV, lecturing you on your "mutual indifference," as "your eyes glaze over." She leaves plenty of chairs, but you have to sit practically in her face to make out her words.

You enter confined spaces to face black "intruders" with deeply illuminated eyes. You witness beatings by LA riot police, to the tune of "What's Going On?" You see blaring headlines about racism and race from The New York Times. You hear a lecture on liberals being "extra self-conscious" in trying to say the right thing. You have to decide what counts as ironic and even funny, what angry and portentous. Piper is happy to be all of them at once.

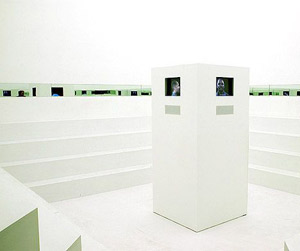

She turns the atrium downstairs into another tight space, with a work from her last appearance at MoMA in 1991—a white box within the white box, with stadium seating. Inside is a white column topped on each of four sides by a black male proclaiming that he is not a stereotype or your worst fears. He is not evil or stupid, dirty or selfish, horny or smelly. Piper describes the space as a Minimalist amphitheater, like the one in which Romans threw Christians to the lions. You might wonder which is worse, to play the murderer or the victim. You might wonder, too, which applies to you.

Then again, a confined space can also be a retreat, at once comforting and empowering. It can, for example, be a voting booth, and she places a row of them outside as well, with photos from the civil rights era. They invite you to "list the fears of how we might treat you, think of you, and know about you." (Notice the slippery pronouns.) One late confrontation has you pass through an empty room that you are required to hum to enter, but you choose the song. I chose "Love Me, I'm a Liberal."

A private space can also be the shared scene of a party, and Piper has turned many a performance into a dance. She has danced to funk music at the Whitney and alone—in comic homage to her insecurity, for her "Big Four Oh" birthday. She has invited black kids to dance on the sidewalk, to Billie Holiday and "God Bless the Child," and they enjoyed it. I did, too, guiltily or not. The show offers no end of opportunities to feel guilty or to join the party. It also dares you to pin her down.

Her body presence

Born in 1948, Piper starts out ordinary enough—much, in fact, like an ordinary white girl. The show opens with paintings from age 17, in a psychedelic style picked up from, say, that Jimi Hendrix album cover with curvy colors. They feature Alice in Wonderland, and already the artist is down the rabbit hole. She includes LSD in the titles, and you never know whether she was tripping or just thrilled to the music and culture around her from those who were. She might have picked Alice because she identified with her. She might have picked Alice, too, because of the Jefferson Airplane's "White Rabbit."

Juvenilia aside, Piper did not take right off to confrontation. She studied at New York's School of Visual Arts and learned from Sol LeWitt. She also completed a doctorate in philosophy, at Harvard under John Rawls, the author of A Theory of Justice. (Rawls does not mean racial justice, but then it is his book and not hers.) She wrote on Immanuel Kant and G. W. F. Hegel, rather than postmodern theory in art. She became the first African American with tenure in philosophy, and she still lectures on Kant in a makeshift theater outside the museum's galleries.

Her version of Minimalism is even more systematic than LeWitt's, to the point of tedium—as she must have felt in abandoning it. Still, it ventures nicely into three dimensions like Carl Andre, on both walls and floor. It anticipates her conceptual art and performance art in its text spelling out the rules. It may also relate to the analytic philosophy of the time, with its exploration of how we know what we know. She speaks in one work about consciousness as an ordering in space and time. It takes her, she continues, into the here and now.

The early work may anticipate her political and performance art as well—and Michael Fried back then did criticize Minimalism as theater. In picturing Alice or posing with a Barbie doll, which she then dismembers in drawings, Piper must have wondered how far she could identify with either one. Studying Kant's idealism, alone on the Lower East Side, struggling with Kant to move from the mind to the world, she photographs herself in a mirror "to reassure herself of her body presence." The entire image is all but black. Later, in facing others, she says that she is looking for an escape from "the noose of anxious ambiguity," and she may well mean it. "I'm afraid of the day when I really lose control" and "cry for help."

Politics had to have a pull, if only because the systems had to run their course. "Good ideas are necessary and sufficient for good art," she writes, echoing the language of formal logic. Yet ideas in art must remain "implicit" and "relative to one's esthetic." Politics also had to have a pull between events around her and her light-skinned, long-haired image in a mirror. Later she depicts herself both exaggerating her "negroid features" and "as a nice white lady." She is assaulting demands or refusals that she pass for white, but also exploring the possibilities.

The confrontations begin in 1970 at Max's Kansas City, where she performed blindfolded, and they pick up the pace starting in 1973. For seventeen months, Piper wore an Afro wig, glasses, and Groucho Marx mustache as The Mythic Being, walking the streets and placing ads in the Village Voice, with speech balloons out of the comics. ("I embody everything you most hate and fear.") It makes her into the stereotype of a black male, but she looks to me more like Frank Zappa. Either way, she is and is not what she appears. "You jumped to the wrong conclusion," she observes, "as you always do."

The takeaway

Piper's first overt outrage plays on her doubts as well. She clips the newspapers to spell out the needs of the homeless, as This Is Not a Performance. It insists that this is not just art but life, but it is also dizzyingly self-referential. She draws others into her first confined space, with more clippings, but its soundtrack complains about the pressure of "all this political stuff." For all the irony, she will not be pigeonholed—not even by the stuff of life. She can make political art now, but only by heeding another work's advice, to "pretend to be what you know."

She does a good job of pretending, and it fuels her defiance. The next twenty years are filled with it, including more clippings labeled Vanilla Nightmares, or white fears, overlaid with brutal drawings. The enclosed spaces grow tighter and bolder, like paired black and white chambers. Her unaccented voice grows louder. Her blackness is "not just my problem. It's our problem." She takes pride in the agonies of poverty and the defiant smiles of family and friends.

Still, she claims western civilization as her heritage. Performers wander the museum lobby and sidewalk wearing signboards: "everything will be taken away." It stands for how blacks may feel vulnerable even with the little they have—or how whites may feel vulnerable to "uppity" blacks. Yet it also refers to what Alexandr Solzhenitsen learned in the Gulag: when they take everything away, then they no longer have power over you, and you are free. In her very first sound art, she whistled Bach, and she withdrew her work from one show because she wanted African American artists, black women, and radical women to compete not just with each other, but with everyone.

She can never forget her family tree, going back to the slave of a man named Piper. Yet with For My Sixty-Fourth Birthday, she "has decided to return from being black, to 6.25 percent gray." Maybe she has not given up on shades of gray after all—or, for that matter, philosophy. Existentialism, she would have known, argues that one finds oneself through others and what they see. It takes confrontation. It demands recognition.

It also slackens off. The show show's last room, after the humming, takes her finally into the millennium, with shorter hair. It also takes her from Kantian rigor to yoga. A work lists the stages from ego and synthesis through particularity and separation to possession and grasp. (Well, O.K.) Still, on engraved mirrors and framed, smeared chalkboards, "everything will be taken away."

Piper can go on way too long and with too much sanctimony, but that duration and devotion have made her an ancestor. She collected sweat, hair, and nail clippings long after Victorian England treasured the hair of dead loved ones—but also long before Zoe Leonard collected suitcases, as testimony to the passage through life. As an artist and philosopher, she has made the personal not just the political, but also the blazingly theoretical. For my contract in the Probable Trust Registry, "I, the undersigned, hereby certify that I will always mean what I say." And of course you will, unless, this being art in a show about betrayal, you do not. But then Alice down the rabbit hole had to learn that "I mean what I say" is not the same as "I say what I mean."

Adrian Piper ran at The Museum of Modern Art, through July 22, 2018. For those unable to remember, Phil Ochs sang "Love Me, I'm a Liberal."