Real Life

John Haberin New York City

Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body

What is your idea of what it means to be human—or art? Is it Michelangelo's David, focused, unmoving, larger than life, and poised for action? Or is it a house painter with a roller, his clothes stained with paint and his tarp covering a museum floor?

with "Like Life," the Met Breuer comes down firmly for the second. Right off the elevator, Duane Hanson's black worker could be preparing the walls for, as the subtitle has it, "Sculpture, Color, and the Body." He takes his pose from Michelangelo at that, with one hand to his side and the other raised above a bent elbow. He, too, needs both hands to hold his ground and to wield his weapon. The show's real subject, though, is the question, and it answers with a call to set aside white marble and Renaissance ideals. Huge and often mesmerizing, it also reduces seven hundred years of sculpture to a simple-minded view of art and a degrading notion of real life.

Leaving marble in the dust

Duane Hanson has a gift for deception, and his painter, from 1984, looks more than halfway alive. Still, art and life are often more than they appear. His mock heroic pose glosses right over concerns for race and class in museum workers. (For decades now, Martha Rosler and others have made art that advocates for unions.) David, in turn, shows his command with his oversized right hand, but also the youth and fear in his eyes. By comparison, the house painter looks merely pathetic, not enlivening art but demeaning life.

So often as not does the exhibition. It runs to the ugly smirk of illusionists like Hanson, John Ahearn, and John De Andrea (but not, be it said, the kitsch of Will Kurtz or the greater dignity of the world-weary in the Straus collection). It cannot resist pairing the decorative excess of Meissen porcelain with Jeff Koons, for Michael Jackson and Bubbles. Its choices can seem arbitrary at best. How much sculpture, after all, is not figurative? Yet it ranges widely enough to raise a serious question.

Just what is wrong, it asks, with looking at white marble and wanting more? The curators, Luke Syson and Sheena Wagstaff, argue that people turn to art for the illusion of life, even as elites have relegated the lifelike to something less than esthetic. And people turn to it for good reasons. It can encourage religious awe, scientific study, or just plain fun. It has an "intellectual and psychological potency" that leaves marble in the dust. The show devotes two entire floors, the scale of "Unfinished" at the opening of the Met Breuer, to a revisionist history that explains why.

It runs thematically, starting with standing figures in marble. An opening room includes an early copy after ancient Greece, a late Renaissance Bacchus (but, no, nothing by Michelangelo), and a female nude by Hiram Powers, an American in Florence in 1858. The Met points to the sobriety of Bacchus and the woman's flaccid flesh, as twin refusals to deal with life. It explains that the Renaissance adopted white marble because it could not know that artists in antiquity painted their work. And then it challenges "the presumption of white" with black and white figures by an African American, Fred Wilson—and the off-color plaster of an aging mother by Bharti Kher in 2016, seated on an ordinary wood stool. The next room ditches white for "chromatic classicism," including a miniature Venus de Milo that René Magritte has covered with flesh tones and bright blue.

Already one can appreciate the show's strengths. How many exhibitions can bring together scholarship and entertainment value? How many can move confidently across art history and work from just the last year or two? How many could riff on the Met's collection and think right off of loans from around the world? How many know that Magritte made sculpture—as did El Greco before him? How many can combine the art of illusion with concerns for race, gender, and age?

Already, too, one can see the problems. Without chronology, will everything start to look the same? Will it look slacker, blander, and more meaningless at that? Will you notice when art is breaking the rules and when it is missing out on both past and present? Will it be lifelike or leveling? Is the history at hand even true?

Ingenuity and leveling

It may not ring true even for that first room. True, Bacchus may fall short of life, but then almost no one remembers the sculptor, Domenico Poggini, while Powers wallowed not just in marble, but in American sentiment. What if the show began instead with Michelangelo—or the shock and terror of Donatello in the early Renaissance? True, too, Bacchus may not look drunk, but often in art he does. More terrifying still, sometimes he does not. In a painting by Caravaggio, he has a sly leer as he holds out his temptations.

Artists back then may not have known polychrome marble, but they knew polychrome wood from the Middle Ages. They also found it as clumsy as folk art. And true, Charles Ray takes a girl off her podium and abandons the half turn of contrapposto, in order to meet the viewer's eyes. Yet Michelangelo adopted the pose for its tension and potential for motion, as a means to a greater physical and psychological realism—just as he adopted the fear in David's eyes. He also liked bare marble not just for its idealism, but also for its display of the sculptor's chisel and for its place in architecture and the world. Michelangelo carved David from a block originally intended for the exterior of a cathedral.

The same mix of ingenuity and leveling turns up in every room. This is history you need to see to believe, but not the history you may choose to remember. You can admire the color, but you may find a Tinted Venus from England in the 1850s blander than her precursors after all. You can appreciate the steel gray of a statue by Frank Benson, from 1976, not because it is lifelike, but because it is otherworldly. And wait: Donatello himself turns up with polychrome terra cotta.

A section for "likeness" introduces methods other than casting or carving. It includes funeral masks cast from the dead, along with human hair and blood. A bust of Meyer Schapiro, the great critic, by George Segal in 1977 gains in poignancy once one notices its half-closed eyelids, like those of Kher's mother. And the masks of the dead gain in poignancy once one notices their resemblance to the dying. The section also introduces art as anthropology, with busts of a colonial maiden and a Jewish woman of Algiers.  Sympathy vies with colonialism.

Sympathy vies with colonialism.

One cannot help noticing, too, the pandering. That blood fills a 1991 self-portrait by Mark Quinn—with the refrigeration equipment to hold it in place. Hanson is back with a housewife, and there is no mistaking her stereotyped bourgeois self-indulgence. One is likely to see a celebration of Puerto Rican family by Rigoberto Torres as more tawdry in her light. One is also likely to see a veiled self-portrait of Marisol from across two nude whistlers, by Tip Toland in 2005. A museum-goer or two might land in the same frame, but then the entire show invites one too many selfies.

A section for "the desire for life" raises another question: how conflicted was art in its search for the lifelike? Would it side with the aspiration to the human of Pygmalion, with sculpture brought to life—or would it draw back in disdain of idolatry and lust? Jean-Léon Gérôme painted the first and Lucas Cranach the latter, with French academicism and Reformation fervor. Buster Keaton on a merry-go-round horse, by Koons, rests next to Jesus on a donkey for his entry into Jerusalem, from the fifteenth century. Neither is terribly lifelike, but only the first is a bad joke.

Deviance and torture

The jokes keep coming on the show's second floor, with the help of some very adult child's play. The next section positions marionettes and dolls as "proxy figures." You may know these "deviant playthings" from photographs by Hans Bellmer in the 1930s and, somehow not in the show, Laurie Simmons, but again the museum makes a clever connection. With their movable parts, they fall between sculpture and machines, and artists have long posed them as "lay figures," in place of a live model. A pairing of Ray's Male Mannequin with Phallic Girl by Yayoi Kusama packs gender ambiguity as well. Still, the emphasis, as ever, is on titillation, not critique or politics.

A section for "layered realities" adds smoke and mirrors, like a boy contemplating his image by Elmgreen and Dragset. (And, ooh, is that a lipstick tube on the floor?) An assemblage by Edward and Nancy Kienholz from the 1980s suggests a recent antecedent for the dirty illusionists. Yet the most serious titillation comes next, with "figuring flesh." That means nudity, tormented and proud, just in case you had not noticed it all along. It may also mean the worst leveling of all.

This section sticks largely to two centuries, and it keeps them largely apart. Jesus displays his wounds and his agonies, on and off the cross. And then contemporary art picks up flayed flesh and dismemberment, with Kiki Smith, Oliver Herring, Urs Fischer, Paul Thek, and Robert Gober. The museum offers a passing reminder that anatomical studies (as for Michelangelo himself) were traditionally écorchés, or literally skinned alive. Still, it reduces stacked horizontal nudes by Louise Bourgeois from feminist nightmare to cheap thrills, much as Smith's expression of pain becomes simply demeaning. It never asks whether representations of Jesus were anything but a horror show.

With its trust in realism and illusion, the show cannot help asking: is this life or art? Its final section hedges, with work "between life and art." It also sees the work as between dead and alive. Alison Saar hangs a female nude by her ankles, as the victim of a lynching, for Strange Fruit. The rest, though, take the question lying down.

Paul McCarthy dreams on a lawn sofa, still wrapped in plastic, and a Sleeping Beauty from 1765 still sleeps. The corpse of Jesus, though, or a man in an open coffin by Maurizio Cattelan will sleep no more. What, then, about a Nativity of the Virgin from around 1480, with a pensive Anne giving only modest thought to the infant Mary? Or are all these just much the same, with birth, sleep, and death no more than minor disturbances in the course of life? And what of an old woman scrunched up in bed, by Ron Mueck? Is she anything more than white sheets, dry skin, and bad hair?

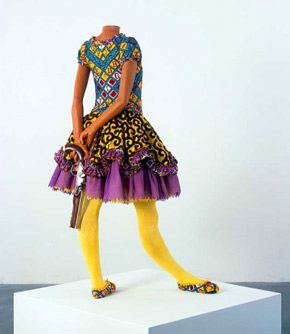

Is "Like Life" anything more either? On the way out, one can compare a young dancer by Edgar Degas with an African ballerina in much the same pose by Yinka Shonibare, from 2007—for their real clothing, their ethnicity, their authenticity, or the dance. Would either have wanted to see the girls entirely as surfaces? Would either have wanted to subordinate their distinct ideas of the contemporary or of a coming of age? For this one last time, everything has fallen to the same level. At least they both look truly alive.

"Like Life" ran at The Met Breuer through July 22, 2018.