Women on the Line

John Haberin New York City

Radical Women: Latin American Art

Juanita McNeely and Multiply Identify Her

The artists in "Radical Women" put themselves on the line with every demand to be seen and to be heard. They put you on the line as well. Lea Lublin raised her new-born son in a museum, while Graciela Carnevale padlocked the gallery with her unsuspecting audience inside. What they cannot do is make sense of gender, class, and history.

Blame the curators and not them—or blame the times. The idealism of the 1960s was already fraying, and women had still not broken through. Still, the Brooklyn Museum shows them trying, in fifteen countries.  Often today, shows are recovering past artists, including Latin American women like these, but here the emphasis is on their initiative. It comes through, too, with a feminist from Missouri, Juanita McNeely, and so does the toll of life on the line. It divides and multiplies with "Multiply Identify Her" at the International Center of Photography.

Often today, shows are recovering past artists, including Latin American women like these, but here the emphasis is on their initiative. It comes through, too, with a feminist from Missouri, Juanita McNeely, and so does the toll of life on the line. It divides and multiplies with "Multiply Identify Her" at the International Center of Photography.

Close-up on the body

Those radical women lived in Latin America, the site of brutal regimes and right-wing hit squads. They lived in the macho culture of East LA. They lived between nations, whether born in Europe and based in the Americas or born south of the border and based in New York. They witnessed the decline of colonialism, vanishing indigenous peoples, and limited opportunities for their art. These were tough years for women seeking recognition and dangerous years for everyone else, from 1960 to 1985. They left their mark anyway, with their "Art of Defiance," with themselves at the center of almost every work.

The demands ring out loud and clear from the entrance, with the shouts of The Three Marias, by Judith F. Barca. Straight ahead, Marisol multiplies her self-portrait in wood seven times, each with a different countenance. Nearby on video, Anna Bella Geiger repeats, "I am Latin American. I am Brazil." The self-portraits can run to stereotypical nice girls like Regina Vater, mean girls like Sylvia Salazar Simpson with Chicano hair and makeup, a plywood cutout for Marta Moreno Vega, a toilet and tampons for Sophie Rivera, a banana-clad woman in a banana republic for Victoria Cabezas, or a pregnant woman with her demons for Poli Marichal. For Sandra Llano-Mejía, survival can mean nothing more than a pulse and an EKG.

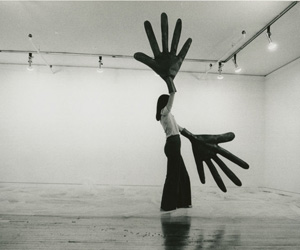

It can allow an evasive dance for Sylvia Palacios Whitman, in a long skirt and with hands half the size of her body. Antonieta Sosa weaves between chairs, and Letícia Parente climbs up on one, while Yolanda López leaps up in brighter colors, and Lourdes Brobet bursts out of a paper bag. Marta María Pérez brandishes a kitchen knife and Anna Maria Maiolino takes scissors to her face, while Ana Mendieta pictures herself in a rape scene. In photographs, Vera Chaves enlarges scrapes from her skin to raised flooring, while Silvia Gruna lies in sand and Yeni y Nan smears her flesh in mud. Even steel shards can stand for a woman, as The Hysterical One from Feliza Bursztyn. Gloria Gómez-Sánchez asks only to Make Your Life Your Own.

So many demands can be a blessing or a curse. The curators, Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta with Marcela Guerrero of the Hammer Museum, include more than one hundred and twenty artists (but, oddly, not Virginia Jaramillo or Marta Minujín), almost all little known, in some two hundred and seventy works. Multiple time lines by country make things still more off-putting rather than clearer. Sections for self-portraits, feminism, and social places can look much the same. So can those for "Mapping the Body," "The Body as Landscape," and "The Erotic." The show's very title sounds suspiciously like a reprise of "Black Radical Women" in Brooklyn last year or "rAdicAl preEsEncE" at the Grey Art Gallery in 2013.

Where those shows placed art in a context of activism, here women place activism in context of themselves. Like the Phelps de Cisneros collection at MoMA, It extends the recovery of Latin American artists, Brazilian art, and Caribbean art, but at risk of drowning out the very voices that it hopes to reclaim. Artists as inventive as Lygia Pape and Lygia Clark in Brazilian art appear as still more bodies in close-up, much as for Adriana Varejão today, and Cecilia Vicuña not at all. They are all too likely to be seen but not heard. Men are barely to be seen at all—apart from Yanomama tribesmen for Claudia Andujar, the "disappeared" as skulls for Ester Hernández, or the huddled masses in a dark painting by Gracia Barrios. Few look beyond themselves to the real world of police violence, like Nirma Zárate, and domestic labor, like hands in a sink and toilet in photographs by Ana Victoria Jiménez.

You may blame only yourself if you lose track of nations and regimes, left and right. Or you may settle in to enjoy what Minujín calls Mayhem. You may find humor in a "wash and wear" Venus after Sandro Botticelli by Beatriz Gonzáles. You may find poetry in waves washing over pyramids by Sara Mondiano. You may see tortured or erotic flesh in an enormous body bag from Carmelo Gross, a mattress for Marta Minujín, or dismembered mannequins from Nelbia Romero—not so very far after all from Laurie Simmons. Or you may silence the voices yourself by leaving well before the end at the cost of, sadly, missing justified demands and some terrific art.

Climbing the walls

Maybe people these days are refusing to grow up, or maybe they are just in need of a hero. Wonder Woman and the Black Panther are not only box office, but role models or even breakthroughs. Take heart, though, boomers: Juanita McNeely was there forty years ago and thoroughly adult. In her paintings, she scaled walls and windows as easily as Spiderman—and with much the same hand-over-hand pose. She was also confronting her sexuality, relationships, representation, and paint.

A downtown gallery takes her back to the 1970s and also brings her up to date. It may come as a surprise. As the show points out, McNeely did not appear in a museum-wide survey of "art and the feminist revolution" in 2008. As with "Radical Women" in Latin American art, the acts of recovery keep coming, and critical judgments are not getting any firmer or easier. The artist, I learned, belonged back then to "Fight Censorship"—along with Louise Bourgeois, Judith Bernstein, Aneta Grzeszykowska, and Joan Semmel. Like Betty Tompkins and Mira Schor, the group shared an interest in claiming eroticism and its representation for women.

She scales one window naked, looking back over her shoulder with dark hair and eyes. She appears to have burst through another without shattering it, with a star on her breast and pubic hair in bright red. Still, she offers no pat assurance that porn becomes a badge of honor in the hands of a woman. She may turn her head away, but she could still be seeking the comforts of home in the outlines of house plants behind the glass, like cutouts for Henri Matisse.  The window in the second painting might just as well have ejected her, leaving its mark in blood. From the expression on her face and her spreading hair, it appears to have caught her by surprise quite as much as the viewer even now.

The window in the second painting might just as well have ejected her, leaving its mark in blood. From the expression on her face and her spreading hair, it appears to have caught her by surprise quite as much as the viewer even now.

Her contested interiors also include the space of the mind. Climbing the walls does, after all, have a less comforting sense. Other imagery runs to monkeys, skeletons, her upper body bound as in a straitjacket or a mummy, and a pile-up like lost souls in an apocalypse. She is also open to sharing space as well as claiming it. In a double portrait, she sits beside her husband, Jeremy, who holds a friendly black dog. The window has become light and shadows cast on the floor.

Perhaps it was all along—which would explain how McNeely could scale it or keep from breaking it. She is no less strong and unsettling for that. She brings her imagery together in a full nine panels, as Moving Through in 1975. It alternates broad and thin scenes, like the center and wings of a Renaissance triptych three times over, as it wraps around a corner. It also alternates pride and joy with terror and pain. As a cancer survivor many times over, starting with a diagnosis in her first year of college, she knows them all. After years now of affirmation rather than irony in politics and art, from a triennial to Mickalene Thomas, I am grateful for them all as well.

Entering her eighties, McNeely is still a survivor, and the show ends with a brief leap ahead. Her colors have intensified from the earlier silhouettes, on behalf of realism and expressionism alike. Bald figures dive into a fiery red, like men in hell or women after chemo. Another crawls through a swirling blue sea with the aid of that same black dog. In a final work, a flower fills the picture plane with its warm reds and yellows, almost out of Georgia O'Keeffe and O'Keeffe drawings. It could stand for McNeely herself, her private parts, the light in her mind, or her domestic desires.

Divide and multiply

For roughly three years, Roni Horn followed as a girl became a teen. Her niece kept changing not just with the years, but with moods and the time of day. She delighted in the camera, to the point that the forty-eight photos from 1998 to 2000 become changing characters on opposite sides of a wall. She could be as many young women as Cindy Sherman—or as few as an insistent selfie on Instagram. Horn calls these untitled film stills (to borrow, if I may, from Sherman) This Is Me, This Is You, but then who am I, who is she, and who are you? She contains multitudes.

So does any woman, to judge by "Multiply Identify Her," at the International Center of Photography through September 2. The curator, Marina Chao, hits all the right buttons, no doubt, from Postmodernism to pride in gender and a woman's self-image. The nine artists leave open whether they are asserting themselves, multiplying themselves, or tearing themselves to pieces. (Horn herself has used anything from Isabelle Huppert to sculpture as a stand-in and has said that her gender neutral name gave her an advantage.) Geta Brǎtescu calls that much more attention to her four eyes by placing them in an old wood frame. This is mirroring, but also self-imagining and displacement.

The theme allows a mix of stills and video. (ICP has seemed restless with photography since its move to the Bowery, although Henri Cartier-Bresson and Elliott Erwitt reign for now upstairs.) Either way, nothing comes unaltered from the camera. Christina Fernandez seems all the more personal with her features displaced, in black and white, but her Chicana feminism, as with Amalia Mesa-Bains and what she calls Domesticanx, becomes itself an alter ego. Stephanie Dinkins goes face to face with BINA48 (alias Breakthrough Intelligence via Neural Architecture, 48 exaflops per second), with the advice to "befriend a bot." They look equally cuddly and equally chilling.

The theme allows, too, an artist as dedicated to painting as Mickalene Thomas. The show looks better for foray into her multi-channel video, and so does Thomas. She seems more disarmingly herself, without the patterning and gilding. She is also more disarmingly others. She lip-syncs to Eartha Kitt, and so does the artist's significant other. Kitt appears, too, and the threesome could pass for one.

"Do I Look a Lady?" Kitt and Thomas just thought they might ask, and they answer with a hesitant yes. So does Wangechi Mutu, whose photocollage is both a self-portrait and a flower. (She has alluded to her Kenyan heritage and the decorative arts before, with images form African folklore in fabric.) So, too, does Lorna Simpson, who gives her stylish self away with her titles—Big Yellow, Blue Wave, Red Head, and White Roses. Not so Barbara Hammer (here and in "Trust Me" at the Whitney) with the raking light of an x-ray across her back twice over, as What You Are Not Supposed to Look at. Sherman may have given way to adolescence, but film noir is back.

In more high tech, Sondra Perry converts a three-channel work station into an exercise machine. As always, she boasts of her ambition while subjecting herself to compulsion. Gina Osterloh dances with her shadow—harkening back to Fred Astaire in Swing Time, but also to Sylvia Palacios Whitman in Chile or to Man Ray with The Rope Dancer Accompanies Herself with Her Shadows. The trouble with multiplication is that it can lead anywhere, and the choices can seem merely arbitrary and fashionable. Simpson could just as well have appeared with her many lips (shown here) as tokens of African American identity. But then, when a show breaks so thoroughly into pieces, why fix it?

"Radical Women" ran at The Brooklyn Museum through July 22, 2018, Juanita McNeely at Mitchell Algus through May 13, and "Multiply Identify Her" at the International Center of Photography through September 2.