I Had No Idea

John Haberin New York City

Lucy Lippard and Eric Doeringer

Materializing Conceptual Art

"Materializing Six Years" has trouble deciding whether to be a display of art or a book. Come to think of it, that may make it a fine definition of conceptual art. It may explain why an artist today, Eric Doeringer, is still looking to conceptual art for "The Re-Materialization of the Art Object." It may also hold clues to the emergence of conceptual art.

Painters often think of conceptual art as at best a hedge, where criticism crosses into art and art into criticism, and they do not mean it as a compliment. Museum visitors, too, may find conceptual art discomforting, but conceptual artists mean it that way. Piero Manzoni did, after all, preserve a cylinder of his own, er, excrement in 1961, and his title chose instead a four-letter word. Vito Acconci made art in 1969 out of following strangers down the street.  Besides, both art and a book are malleable, permeable ideas, with a slippery space in between. That makes conceptual art hard to display and even harder to pin down, but now the Brooklyn Museum pays tribute to six years of art and to a single book on conceptual art, by Lucy Lippard.

Besides, both art and a book are malleable, permeable ideas, with a slippery space in between. That makes conceptual art hard to display and even harder to pin down, but now the Brooklyn Museum pays tribute to six years of art and to a single book on conceptual art, by Lucy Lippard.

The idea of an idea

Henry Flynt coined the term concept art in 1961 to describe the logic of chance operations, as for John Cage and Fluxus. Already, though, Yves Klein had had his 1960 "leap into the void"—or at least a photograph of himself by Shunk-Kender, arms outspread, seemingly about to crash into the street. A young Robert Rauschenberg had his Erased de Kooning in 1953, and Willem de Kooning had in turn discomforted him by playing right along. The whole idea, and I do mean idea, goes back anyway to Marcel Duchamp, a certain urinal, and any number of poses. As Tristan Tzara says in Tom Stoppard's Travesties, "My art belongs to Dada, because Dada she treats me so well." By those standards, Lippard might have come downright late to the game.

Hardly. The New York Cultural Center devoted a show to conceptual art only in 1970, and Lippard had been following it every step of the way. Her Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, published in 1973, is in fact a kind of diary. It begins the year of her book on Pop Art, and it wraps around the Sackler Center for Feminist Art, with its six years in large numerals on the wall. It builds a case for Lippard's central place in conceptual art and conceptual art's place for Lippard, a critic often as not identified with Pop Art or feminism. It also challenges her, with its acts of materialization.

It does not make the challenge easy. The hedge between art and book means insights, but also an awkward, exhausting show with hardly space to materialize anything—the space of what one recent exhibition called "The Feverish Library." It has ninety artists and nearly twice that many objects, in just two long but narrow rooms. It has a visitor all but bouncing off the walls, with each year split between them. It mixes art, photographs of art, and instructions for making art with exhibition announcements and typewritten documents from the critic herself. When Lippard assigns her students at the School of Visual Arts to describe, the imperative could cross over into a work of conceptual art.

She crosses all the way over with a longer statement to accompany an exhibition. "It doesn't matter what this says," she concludes. "Is a review in itself a fake?" I hope not, but things are getting interesting, and one can see how capacious the idea of conceptual art is—not just at its emergence, for also for today. Lippard makes that clear enough when she gives her book a sub-subtitle and a sub-sub-subtitle. She calls it "a cross-reference book of information on some esthetic boundaries: consisting of a bibliography into which are inserted a fragmented text, art works, documents, interviews, and symposia, arranged chronologically and focused on so-called conceptual or information or idea art with mentions of such vaguely designated areas as minimal, anti-form, systems, earth, or process art occurring now in the Americas, Europe, England, Australia, and Asia (with occasional political overtones)." Are you with me?

Not to worry, for one has a taste of all those in Brooklyn. The curators, Catherine Morris and Vincent Bonin, start quite apart from conceptual art, because Lippard did. Her 1966 show at Fischbach, "Eccentric Abstraction," includes some experts at physical comfort and discomfort—in Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse and her Expanded Expansion, and Bruce Nauman. (Note that three of this show's eight artists are women, and Carolee Schneemann soon posed for Nauman as Manet's Olympia.) It also inspired a crossword puzzle by Nancy Holt, starting with "What a Nauman work sometimes appears to be." Alas, "blank" does not fit in the blank.

In no time, too, one has a definition of conceptual art—or maybe not. Joseph Kosuth displays a dictionary definition as a silkscreen, of the word word, subtitling it Art as Idea as Idea. The viewer or reviewer, in turn, then forms an idea of an idea of an idea. It is not an infinite regress, but it is treacherous ground. Step back from the show's crowded walls, and it may slip out from under one. Did I say that the first show devoted to the subject was called "Conceptual Art and Conceptual Aspects"?

Between art and book

Maybe it helps to notice a certain ambiguity. One can have art driven by an idea, in any medium, what Helen Marten calls a "structural agenda," or art restricted to an idea, so that it can never be executed. And in a period roiling in ideas and media, that allows for a lot of possibilities. Conceptual art can be land art, like a project for DFW airport by Robert Smithson, or a chalk line on the floor for Ian Wilson. It can be a mere "duration piece" for Douglas Huebler, who awaits the capture of the most wanted. It can be an entirely physical and familiar work of art—or newly strange view of the gallery itself.

Dorothea Rockburne has her typically nuanced abstraction, although of chipboard and crude oil, and Josef Beuys has his felt—here with a speaker reciting yah yah yah yah. Alice Aycock's Cloud Piece surrenders only a contact sheet, but still of clouds. Richard Serra issued only instructions for that wood wall, but it is a wall all the same. Directions for how much paint to use, from Lawrence Weiner, hang near Jo Baer's abstraction, its black and colored stripes framing a field of white. The different kinds of players indeed hung out together, like Kosuth and Weiner. You will not be surprised to see the first in the dark glasses of a hipster, the second in a badly trimmed Bay Area beard.

It can be a project, like Every Building on the Sunset Strip for Ed Ruscha, or water towers for Bernd and Hilla Becher—and one virtue of a context in conceptual art is to see them as a project. "Art by telephone," with a contribution by Sol LeWitt, left an LP. Eleanor Antin photographs 100 Boots Facing the Sea, and I dare you not to think of women and shoes. A time before social media had its share of postcards, like reports on his awakenings by On Kawara or Barry Flanagan's hole punched in a postcard of the sea. It had its impersonality, like Robert Barry's catalog of index cards or Lippard's questioning of criticism. It had its confessions nonetheless, as from Lee Lozano, who was "smoking too much."

In the Vietnam era, art definitely meant politics. Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, and Robert Ryman joined others at Paula Cooper in 1968 on behalf of peace—while an Art Workers Coalition demanded, "Is the Whitney Relevant?" Graffiti in Argentina, photographed by the Rosario Group, cries out that Tucumán Is Burning. Most often, though, politics meant the politics of art, just as so much art back then meant reflection on art. Lozano also took a break from her creamy paintings in 1969 to propose a "general strike for peace," but she meant a strike of museums. When Hans Haacke collects museum "visitors' profiles," in 1971, he does not ask for political opinions or party affiliation.

In documentation or recreation, the very distinctions start to blur, much as for Rodney Graham: the material becomes a record, while the immaterial materializes before one's eyes. That dynamic plays out with the austere leaders of conceptual art in England, the collectives known as Art and Language and as Art and Culture. When Mel Ramsden for A&L announces that "the content of this painting is invisible," he keeps its secret beneath a visible coat of black. When John Latham for A&C sets out a leather case of letters, photostats, and vials, he buries them in mystery. When Stephen Kaltenbach leaves a steel cylinder with instructions to "open after my death," it bears an unmistakable resemblance to Manzoni's shit.

One can easily dismiss conceptual art as a stunt—and an ironic one at that, like Robert Kinmont's 8 Natural Handstands in 1969 or so much of art these days. One can write it off as a relic, like Christine Kozlov's Information Theory, reduced to film reels and a tape deck. One can wish that the space between art and book had truly become an artist's book. If the art seems disappointing and unforgiving, though, it had already turned its back on the commercialism of installations today. And if its definitions seem cryptic, even conceptual art may resist being put into words. Painters, too, can relate to that.

Conceptual art as object

If you think you have seen it all before, you probably have. An artist, Eric Doeringer, may politely disagree, and, you know, he has a point, too. Thoroughly confused? Uncertain whether even to call it art? I guess that is just the nature of conceptual art, or is it? In "The Re-Materialization of the Art Object," Doeringer has every right to ask.

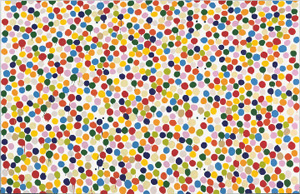

His Lower East Side gallery seems to offer another handy survey of conceptual art, but reality—what a concept. A pair of Damien Hirst dot paintings (but not the "original" shown here) hangs casually interspersed with Richard Prince and his Marlboro men. An On Kawara date painting in white on black hangs so far above the desk that no one seems to care. One could almost miss a gloriously detailed wall drawing, too, on the way in. After all, Sol LeWitt approaches monochrome and chaos with his obsessive instructions, pencil leaves light traces, one has to squeeze past, and anyway it is just the wall. Besides, surely conceptual art belonged to a generation that one had almost, finally, brought oneself to forget.

His Lower East Side gallery seems to offer another handy survey of conceptual art, but reality—what a concept. A pair of Damien Hirst dot paintings (but not the "original" shown here) hangs casually interspersed with Richard Prince and his Marlboro men. An On Kawara date painting in white on black hangs so far above the desk that no one seems to care. One could almost miss a gloriously detailed wall drawing, too, on the way in. After all, Sol LeWitt approaches monochrome and chaos with his obsessive instructions, pencil leaves light traces, one has to squeeze past, and anyway it is just the wall. Besides, surely conceptual art belonged to a generation that one had almost, finally, brought oneself to forget.

The curator, Lynn del Sol of {CTS} creative thriftshop, can justly claim to nurture often overlooked recent memories—and in difficult circumstances at that. She exhibited the special combination of sculpture, performance, and sound art by Amy Greenfield in a corner of Williamsburg by the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, just as neighborhood galleries like that one were on their way out. Clearly this time she has cashed in an awful lot of chips for so modest a space. As surveys of conceptual art go, too, this one is far more accessible than the survey in Brooklyn based on Lippard. Still, the whole point of conceptual art is that things are exactly what they are and no more. What you see is what you see, and if what you see is unlikely, there may be a reason.

By now you will have guessed that Doeringer pulled off the whole thing himself. The black painting bears a date from Doeringer's life, in the present. So do postcards announcing the artist's activities, again after Kawara. He models All My Clothes, after Charles Ray in 1973, and takes a few shots at tossing balls in the sky until they line up, after John Baldessari, but in the rural northeast rather than LA. He serves up all eight hours of the Empire State Building after Andy Warhol, but on a small, portable flat panel that Warhol would have envied. As for the rest, you take the quiz, and consider the challenge a work of conceptual art.

Call the show a copy, a recreation, an appropriation, an installation, rephotography, a performance, or an original, but that in turn points to the slippery definition of conceptual art. Is it something never to be made, to make only once, or to make again and again? That elusiveness makes the whole show, too, something of a litmus test for the viewer. Those who see commercialized art as a loss of the handmade, if not of western civilization, can throw the usual fit. After all, conceptual art has gone through more than enough ironic takes on irony and appropriations of appropriation, with contemporary artists after the "Pictures generation" after late Warhol after Dada. The needed recreations in a Marina Abramovic retrospective already felt sadly like museum pieces, and the Young British Artists already earned more disdain than outrage as what I called "Neo-Neo."

Can Doeringer change things, with his "re-materialization"? He has painted Hirst's dots without assistance, and he calls attention to the material objects of others—as with stain paintings after Ruscha, whose stains have now aged a good many years. Still, conceptual art is not going to have one story any time soon, not even this one. Some things have had their hype dismissed often enough without his help, while others regain their vitality by a return to the present. In the best, though, the conceptual underpinnings of the conceptual art have themselves changed. With Prince after the death of cigarette ads or Empire captured with digital precision all the way from Brooklyn, reality is no longer so certain a concept.

"Materializing 'Six Years': Lucy R. Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art" ran at The Brooklyn Museum through February 3, 2013, Eric Doeringer at Mulherin + Pollard through November 10, 2012. Related articles look at conceptual art versus the art object, conceptual art versus the handmade, and conceptual arts in the plural.