The Dreamwork of Politics

John Haberin New York City

An Interview

In spring 2007, a graduate student sought out the views of myself and others on political art. May I share the conversation, with just a slight bit of editing? It offers me a good way to point to themes of art and politics elsewhere on this site.

Introductions

Q: What is your full name and age? Your profession?

John Haber, 52. Writer/editor.

Q: You mentioned you are not an artist. How did you become interested in political art?

I am an arts writer. It comes with the territory, and I feel more and more a part of it, although my first interests were the Renaissance and abstract painting.

Q: How long have you been interested in political art?

Perhaps from the start without even knowing it. I got to know art through the Renaissance, Jan Vermeer, Paul Cézanne, abstraction, and the rest of a very traditional art history. But such issues are always there, and one has to be aware of them. The Renaissance is a reconsidering of beliefs and empires, both religious and secular. The Dutch are asserting a new national ideal following independence from Spain. You can take it from there.

The subject of politics

Q: What is are some of the topics you have seen modern political art portraying?

Lots of things. One could say that modern art began with Edouard Manet, who dealt with French imperialism (The Execution of Maximilian) and, in Manet's Olympia, with what Émile Zola had called in the title of one novel the "underside" of Paris. For all the overt representations of war, such as Guernica, there are political implications in the interest of Pablo Picasso and others in "the primitive."

People have often seen Abstract Expressionism as a boast of American culture's independent stature. Others call it an avant-garde's assertion of creative independence in the face of capitalism and kitsch. Either way, however, it has political implications. Arshile Gorky echoed memories of the Armenian genocide in his childhood. One could go on for a long time without reaching the war in Iraq.

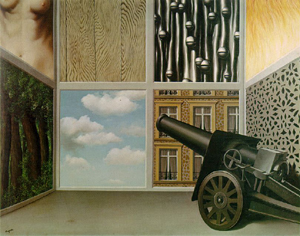

Right now, that war is necessarily on the mind of plenty of artists, along with censorship and torture. So do art institutions themselves. Once again, what an earlier generation would consider self-referential art—and thus formalism—has political implications, almost as when René Magritte called a painting On the Threshold of Liberty. The politics of art is politics, too, not to mention a contentious branch of economics. Feminism, too, is critical to art of the last two generations.

Conservatives often deride political art and critical theory for ignoring art's special realm. In this way, they can also associate the politicization of art with "anything goes." They want to claim the moral authority of the public side of art, while also demanding that art restrict itself to the personal—to what Richard Rorty, the philosopher, calls " 'taste' as bundles of idiosyncratic beliefs and desires." One can never have it both ways. In fact, one can never fully separate the two sides.

As Rorty continues, "The traditional picture of the self as divided into the cognitive quest for true belief, the moral quest for right action, and the aesthetic quest for beauty (or for the 'adequate expression of feeling') leaves little room either for irony or for the pursuit of autonomy." It goes with a politics that similarly denies autonomy in the name of a rugged individualism.

Political art today

Q: What role, in your opinion, does political art play today?

A philosopher, Donald Davidson, had a challenging explanation of metaphor. People often say that metaphors are compressed similes, or people say that they have both a figurative meaning and an implied "real" meaning. Davidson believes that even metaphorical sentences mean exactly what they say. To him, what might be false taken as statement need not have another, explicit metaphorical meaning that is true. Rather, metaphor has the function of pointing to other matters that one had not noticed before—even headlines that governments had hoped to eradicate.

One can think of political art in much the same terms. In fact, one can think of all art that way. Again, one should not see politics as a nasty or necessary intrusion on the lovelier business of art. Artists do not make statements: they make art. The art may just happen to point everywhere and nowhere at once.

Q: Do you think political art has to be obvious in order to convey its statement? Or is a subtle statement more successful?

Art has to be understood, and yet it also has to avoid such a reductive understanding that it contributes nothing. That, I suppose, is why one has textbooks on modern art. However, it is not a matter of clarity or subtlety, critique or complicity. Art makes a political point thanks to a different kind of intermediary position. Art is a human being's creation and a viewer's experience—both, in a sense, private acts of the imagination. At the same time, these imaginings take place in a more public space than a daydream.

Art's public space means more than memorials or even sculpture parks. It derives from its subject matter, its stylistic precedents, its patrons, its display, its influence, and more. Art is most vital when it actively encourages that intersection between individual experience and a public space. So, too, are democratic politics and cities.

Memories and dreams

Q: What aspect of political art interests you? Are there particular topics, periods of time, mediums, etc.?

As I say, I have traditional Western biases. I shall be a dead white male myself one day.

Q: Who is your favorite artist or what is your favorite piece of work? Why?

Art is not American Idol, but a Web site allows me to accumulate memories of plenty of favorites. My next goal in life is to see the Masaccio chapels in Florence.

Q: Is there anything else you think I should know about you or anything else you would like to tell me about political art?

It is something I keeping trying to answer, which is why I seem to keep explaining it. But to quote Davidson again, he calls metaphor the dreamwork of language. Political art is the dreamwork of politics.

The interview took the form of an email questionnaire. I have taken the liberty of reordering the questions and cheating here and there as well. You try making Davidson clear on first try.