MAD as Hell

John Haberin New York City

Peter Saul, Serkan Ozkaya, and Joseph Beuys

For once, Peter Saul was "stuck." In a painting of that name, he looks genuinely perplexed and self-critical, with the malleable features and Day-Glo colors of all his characters.

He had taken aim at himself twenty years earlier, in Self, with the labels surrounding his face leaving him torn between abuse, esteem, knowledge, and expression. Still, the knives sticking it to him in 2007 come from without. His overdose of irony may apply to him as much as anyone, but it will take a lot more than that to disturb his certainty about who wields real power. Now back to the usual suspects, in Saul's cartoon of American politics at the New Museum. Does it owe more to MAD magazine than to Marx? Serkan Ozkaya and Joseph Beuys could well pull their activism right out of a cereal box, but it is meant for adults.

Walk all over the workers of the world, and they will spring right back—with greater vigor than ever. They can hardly help it. They will, that is, if they are Proletarier Aller Lände for Ozkaya has fashioned them all, twenty thousand of them, from foam rubber. And you can indeed walk all over them, for he has carpeted the front room of his gallery with them. You may consider yourself the oppressor, willingly or not, but no matter. They put a spring in every step.

Teen rebel

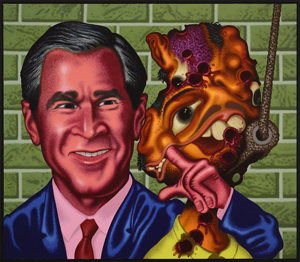

Peter Saul has become a critical favorite, and why not? More than a few critics have grown up on him, even as he skewered them in paint. He must have weaned them off MAD magazine back when and into art. Not that they have had to leave Alfred E. Newman or his heavy shadows behind. A grinning creature much like Newman accompanies politicians in Saul's paintings from Ronald Reagan as California's governor to Donald J. Trump. George W. Bush sticks a finger in the creature's mouth during a visit to Abu Ghraib, but Bush has the more disturbing case of the cutes.

Should you take Saul seriously? He does, after all, quote Washington Crossing the Delaware (without the comedy of Robert Colescott) and The Death of Sardanapalus, an epic of royal prerogative and mass murder by Eugène Delacroix. The curator, Massimiliano Gioni, tosses in references to William Hogarth, Francisco de Goya, Goya prints, and Salvador Dalí to establish his credentials as a painter and satirist. Still, the point for Saul is to take politics seriously, much like Thomas Hart Benton during the Great Depression—and with much the same hard bodies and outsize gestures. If Benton had a passion for comic books and a weakness for dope, he could well have got the joke. Everything else is the delusion of American transcendence.

There are no heroes here, not Josef Stalin or Trump with their guns blazing—nor the defenders of the Alamo cut down by circus clowns. Work from the last thirty years hangs in two rows on three sides of a single tall, large room. Those who start on the museum's top floor may think that nothing for Saul ever changes, no more than his heavy-handed humor and fragile self-esteem. In reality, he had to work his way from contemporary art to MAD. Head down a floor, and you can see how he got his start. Born in 1934, he could easily have been a third-rate Pop artist, and for a time he was.

In Europe, he found himself painting an "ice box," as people used to call their refrigerator, with much the same distrust of consumerism as in James Rosenquist. Mickey Mouse teaches the Japs a lesson out of Roy Lichtenstein, while an S for Superman and a few more S's for dollar signs occupy an electric chair out of Andy Warhol. Saul adopts the unfinished style of early Warhol or Lichtenstein as well—only the hazy brushwork is not an engagement with Abstract Expressionism nor the electric chair an engagement with a culture of death. Here the chair fried Ethel Rosenberg once and brings unequal justice every day.

Saul's breakthrough in the 1960s came with his horror at the My Lai massacre and his anger at the Vietnam War. Perversion, Corruption, Thrill Seeking, Arson, and Torture read the text of his paintings. White Boys Torturing and Raping the People of Saigon, he adds, just in case you missed the point. At least you know where he stands. Over time, he can step back a bit for an aerial view of San Francisco, with equal prominence to the Golden Gate Bridge and a bank, or a grim view of the subway. These are allegories that hide nothing.

His style hardens around 1980 into his signature adolescent male rebellion. In truth, he has less in the way of tits and ass than I remembered, and he turned from Vietnam to celebrate Angela Davis in prison. Still, women in his art are few and far between, apart from an "innocent virgin" in Vietnam. Saul will always be the Bay Area bad boy, much like Mike Kelley and Jim Shaw. In a show called "Crime and Punishment," a floor up from Jordan Casteel at the museum, he gets both to confront the law and to administer punishment. Welcome him for that, as a lawbreaker, but you will just have to grow up on your own.

Essential workers

You may be reluctant at first to tread on art. Most people are, and for Serkan Ozkaya it is part of a work's deliberate confusion of America's class structure. No doubt some visitors will be proper bourgeois (the lucky few who can afford art), but most who care enough to seek out Tribeca galleries are not. The workers, in turn, defy expectations for a class war, since they are neither giving in nor talking back. Bright red, utterly identical, and small enough to hold in one's palm, they seem anything but downtrodden or, conversely, heroic, but they could stand for both. As the exhibition title puts it, "Left Is Right, Down Is Up."

They share the room and its extremes with Ja ja ja ja ja, nee nee nee nee nee, sound art by Joseph Beuys from 1968. Beuys recites the title words over and over, lingering just long enough over the first ja and nee each time that the rest have a special spring, too. Here the artist does all the talking, but he is still notably absent. Those who know him from salvaged clothing, as a diary of his service as a German airman in World War II, will find him for once self-effacing—and those who think of him as solemn and self-involved will be surprised at a quirky sense of humor. The affirmation of ja becomes a dubious ritual, while the negation of nee has him on the verge of laughter. Oh, those wild ups and downs.

Beuys goes back to a decade of near empty rooms. Minimalists asked to consider sculpture as inseparable from the shared space of the viewer, what Michael Fried then derided as its theater. Sure enough, Carl Andre invited one to one walk on it. Ozkaya manages to combine that invitation with Pop Art's fun and games. You may think that you have seen those miniature workers somewhere before, but not in a gallery—in a toy store or in supermarket aisles along with marshmallow Peeps. A sense of found objects nowhere else to be found only heightens the contradictions.

Beuys goes back to a decade of near empty rooms. Minimalists asked to consider sculpture as inseparable from the shared space of the viewer, what Michael Fried then derided as its theater. Sure enough, Carl Andre invited one to one walk on it. Ozkaya manages to combine that invitation with Pop Art's fun and games. You may think that you have seen those miniature workers somewhere before, but not in a gallery—in a toy store or in supermarket aisles along with marshmallow Peeps. A sense of found objects nowhere else to be found only heightens the contradictions.

Stubborn as they are, they cannot always spring back. Quite a few end up on their side, although the artist does his level best now and then to restore them—much as admirers of Carl Andre might help line up his floor plates. Some become damaged and discarded. They spill over into the back room (on the way to photographs by Ruben Natal-San Miguel) and the entryway, with a few outliers almost up against the front door, but in part because someone kicked them there. One might accuse Ozkaya of making light of Marxism and their aspirations, right down to his German title and their Leninist salute. (He himself was born in Istanbul.)

Still, they do spill over, and the work retains its ambitious scale. If it is also funny, all the better, with an eye to commodity capitalism. From high above, they appear as a royal red carpet. From their point of view, at floor level, a visitor's boots are not so much imposing as a joke. The gallery takes both perspectives in an online video. It does a decent job of capturing the experience of the installation, and under lockdown it just had to do.

The show opened the very day that galleries were obliged to close, and this one shares my fear for art after Covid-19 and Covid New York. After three months it lost patience with "virtual exhibitions" and admitted anyone by appointment only, me included. A few days later, New York entered phase 2 of its and art's reopening, and normal hours resumed, with due regard for safety. One will just have to see how quickly others return as well (although initial signs are far from promising). These workers of the world were there all along, though, without the luxury of social distancing. They could be the ultimate essential workers.

Peter Saul ran at the New Museum through January 3, 2021. Serkan Ozkaya and Joseph Beuys ran at Postmasters through July 11, 2020.