The Qualities of Space

John Haberin New York City

Carl Andre at Dia:Beacon and Charles Gaines

Encountering Carl Andre is like entering a minefield. Watch every step, or you may stumble across something dangerous, like a work of art. You may even mistake it for solid ground. Almost all of Andre's work rests beneath your feet, but it can explode upward to alter your experience.

A retrospective at Dia:Beacon uses lumber, bricks, metal plates, and words to do just that. "Sculpture as Place" runs from 1958, the year after he reached New York, to 2010. It presents just under fifty sculptures, plus text art and ephemera like exhibition posters and postcards—little enough that its elements of repetition belong to the art and not to the numbing volumes of a museum blockbuster.  Display cabinets hint at how the work of cutting and chiseling gave way to the structuring of objects. (Who knew that Andre played with magnets?) They all serve as both space and sculpture.

Display cabinets hint at how the work of cutting and chiseling gave way to the structuring of objects. (Who knew that Andre played with magnets?) They all serve as both space and sculpture.

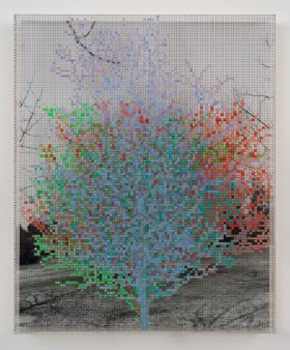

When it comes to Minimalism, Charles Gaines would like to show how it is done. With Walnut Tree Orchard, a series from 1975, each triptych begins with a photograph in black and white of a single tree. A drawing then manifests its shape and tonal range in the elements of a grid, where the number in each cell also stands for its location in the visual field. A second drawing transforms the first, based on previous drawings and predetermined rules, and voilà: the tree has become an orchard. "Gridwork" includes this and nine other series from 1974 to 1989, to spell out his own transformation as an artist. It ends with an explosion of color, scale, and change.

Neither monuments nor hierarchies

To the unfamiliar, Carl Andre can seem dull, formidable, or not even art. They might not care either for his text art, its only tools a manual typewriter and language itself. Andre stirred his share of controversy when he appeared in "Primary Structures," at the Jewish Museum in 1966. Michael Fried in "Art and Objecthood" dismissed Minimalism as theater. I myself got over his forbidding mass only when I discovered that I could walk on it, watch others walk on it, let it direct my attention to the world around me, and (if needed) even set it back to right. Maybe now, though, I can appreciate it as sculpture at last.

Seeing art as object comes naturally to Dia:Beacon. Dia's incredible vision belongs to a former Soho dealer and a wealthy collector, and it leans heavily to the heavy. When it does approach painting, it prefers the dryness of Blinky Palermo, the anonymity of On Kawara, the airy grid of Agnes Martin, and the play with a work's support in Robert Ryman to, say, color atop color in Ellsworth Kelly. Andre did call a series of assemblages Dada Forgeries, including a book with a three-inch hole drilled right through it and a pack of Camels. (No doubt it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than a chain-smoking artist to enter paradise.) Yet art here belongs to the physical field as well as the visual one, and that has advantages as well.

Passport, a scrapbook from the 1960s, includes an image from Constantin Brancusi. And Brancusi could almost have executed Andre's double ziggurat in Eastern pine, but for the stacking that goes into it. Maybe the most impressive single work, though, has more in common with Isamu Noguchi. Noguchi works between industry and nature, and so does Andre. The curator, Yasmil Raymond, writes that he wanted to "vacate the residues of the artist's hand." And yet his materials can be as impressive in their natural variety as red sandstone, quarried in southern Scotland—or the red cedar of Uncarved Blocks, from 1975.

The forty-seven units of Uncarved Blocks fall into just over a dozen groups of from two to four blocks each, set at right angles. They look solid, expansive, and weathered. They might have fallen from the artist's hands, from a Lego set, or by chance. One can think of a single block as found object, a group as sculpture, and the entirety as the gallery. Which is the real work of art? All of them, where repetition changes everything. Weight gives way to what Andre has called "an open set."

Born in 1935 in Quincy, Massachusetts, he worked for the Pennsylvania Railroad, leaving memories of old tracks, old timbers, and rural landscapes. He had attended Phillips Academy in Andover, where he roomed with Hollis Frampton, the future avant-garde filmmaker. And he shared a New York studio with another classmate, Frank Stella. They must have had some interesting conversations. An early Scatter Piece, like those of Richard Serra, has its share of aggression and accident—but in ball bearings and pulley disks. Already Andre was opening up.

Redan, a zigzag of timbers from 1964, recalls fortifications in its title and rural New England in its materials and its shape. Bricks rest on the floor, like Brancusi's endless column turned on its side. A half pyramid comes out of a wall like a stairway to nowhere. Aluminum ingots form smaller pyramids, like a treasury of gold with no value except as art. Sculpture for Andre could be ambitious but never monumental. He was interested not in hierarchies, he said, but qualities.

Minimalism as sculpture

That means the qualities of things, but also of space. Andre's latest gallery exhibition included a corner piece of another signature procedure, metal tiling. A row of timbers from one wall reached almost to the next, daring one to walk around it—or to gamble on the dealer's displeasure and a leap. (With Andre, almost always matters.) A second room held rectangles of twenty-four bricks apiece, in no particular place or order, but in all their possible permutations. They belonged at once to the field of logic, the field of chance, the field of vision, and the field of the gallery.

Dia has vast spaces for Andre's many fields, but less patience with human interactions. In the sole image on its stingy Web site, Andre tiles a corridor in Germany, and people look in a hurry to cross it. Are they crossing a metal carpeting or the floor itself? The work takes its shape from the gallery, while giving shape to perception. At Beacon, one can tread on just one of many tilings. By the time I got to it, I missed the chance, for I had stopped asking.

This is Minimalism as sculpture, in all its variety. The tilings extend from large planes to textured checkerboards, in metals from zinc and steel to copper, magnesium, aluminum, and tin. They reflect light, like six gray mirrors by Gerhard Richter a room away. Metal also uncoils in ribbons and lies in strips like tape. Piping has the looseness of rope for Richard Tuttle. Once again art leaves its mark between industry and nature.

This is Minimalism as sculpture, in all its variety. The tilings extend from large planes to textured checkerboards, in metals from zinc and steel to copper, magnesium, aluminum, and tin. They reflect light, like six gray mirrors by Gerhard Richter a room away. Metal also uncoils in ribbons and lies in strips like tape. Piping has the looseness of rope for Richard Tuttle. Once again art leaves its mark between industry and nature.

The work is insistently literal, but not above metaphor. The stacks create arches and The Last Ladder. The checkerboards may have a parallel in tartans, like those on some of Andre's postcards, from a man concerned for ancestries. A concrete square from 1976 offers a Lament for Children, and grieving need not end with the destroyed playground that inspired it. Breda, a field of crosses in Belgian blue limestone from 1986, commemorates the war for Dutch independence (or The Surrender at Breda by Diego Velazquez in Spain), but it may have one thinking instead of the aftermath of a world war. Like a country churchyard, it guides one's way through time and space.

While the sculpture feels spare, the text art and ephemera crowd in. They show Andre concerned enough for his origins to type and retype Quincy, concerned enough for Modernism to type poetry by Hart Crane, concerned enough for the "particles of language" to type poetry of his own, and concerned enough for repetition to retype the alphabet. He was political enough to insert the name Richard Nixon in place of the king in the Declaration of Independence. And he was haunted enough by all these aspects of the past to retype a chronicle of Lee Harvey Oswald in Russia. His blocky letters match the blocky compositions. They are at once poetry, drawing, and sculpture.

Minimalism is no longer controversial, but Andre is still polarizing. His wife, Ana Mendieta, died in a fall after an argument, and he stood trial for murder. While he was acquitted, some are still certain of his guilt. The death has taken on a feminist narrative of male dominance and a woman Latino artist's neglect. Certainties are dangerous, though, especially with a sculptor so devoted to openness, in his politics and in his art. One may never know him once and for all, but his retrospective should have one treading carefully.

Where black is a number

Sure, others before Charles Gaines have spelled things out, like Sol LeWitt, who manifests the making of his wall drawings right in their titles. When a performer closes the lid of the piano for 4'33", by John Cage, you know what the next 4 minutes and 33 seconds will bring. Even Chuck Close in confronting his growing disability has had to interrupt the perfection of his photorealism, with visible brushwork in a more perceptible grid. Still, LeWitt begins with the directions and lets an image take shape as it will in the hands of others. With Close, skill defies explanation that much more. As for Cage, one could argue that nothing happens at all.

With Gaines, plenty is going on, because the results never set aside their dual origins in chance and nature. A photograph has its own unarticulated rules for picking out a tree, and the result is a landscape that testifies to its growth. Each work unfolds both in time and space—the space of a wall and the time of its making. The numbers in his grids recall the tables of Hanne Darboven, at once encyclopedic and incomplete. Darboven sometimes converted those numbers into sound—and Gaines, an accomplished drummer, took the opposite course in setting aside a career in jazz for art. He is still riffing.

Yet he lets on less than may appear. In Regression, an early series, the number of filled squares in one grid drives the cryptic geometries in the next, but how? Branching spikes arise not from LeWitt's simple rules, but from mathematical equations one will never see much less solve. Incomplete Text Set, from 1979, all but boasts of how hard it is to read. Successive sheets transfer letters from a Pacific Ocean whale watcher's log, based on the arbitrary assignment of color to the alphabet. Even the later transformations of nature have their enigmas.

Born in 1944, Gaines worked amid larger transformations in art as well—from analog to digital and from Minimalism to conceptualism. He taught at an epicenter of California conceptualism, CalArts, although he moved there only as the show ends. The curator, Naima Keith, also argues for a context in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s, but that had its greatest impact on writers, and it ended barely as the show begins. Still, she raises a fair question: Gaines, who grew up in Newark, has appeared in a show of black LA art, and later work has become more overtly political, but is this really about blackness? Can there be black mathematics or a black Minimalism?

Gaines has refused labels, even when he based drawings on the African continent. He counts Adrian Piper as another influence (along with LeWitt, Cage, and Darboven), and he could have found an exemplar of duration in black performance art. Instead, he photographed Trisha Brown in motion, once every three seconds for one minute, in the years that she was also collaborating with Robert Rauschenberg. Maybe it matters that she was dancing Son of Gone Fishin'. His most obvious play with race comes with Faces, in 1978, based on what look like mug shots. Then he reverses black and white, as in a negative, before settling on bare outlines in color.

Somehow the subjects have become people of color, and that color is not black. And yet blackness always has its residue as difference, in an art about nurturing differences. These were also the years when Eva Hesse had gendered Minimalism, and a crucial turn for Gaines was from formulas to the physical—in faces, dance, whaling, plants, and trees. Also in 1978, he produced his greatest tribute to chance, with numbers that record fallen leaves. The show ends with its largest and most dramatic layering, in three dimensions and in glorious color. Grids of trees, in acrylic on acrylic sheets, cast their speckled shadows on the photographs from which he begins, as if to deny once and for all how he does it.

Carl Andre ran at Dia:Beacon through March 9, 2014, and at Paula Cooper through July 25, 2013, Charles Gaines at the Studio Museum in Harlem through October 26, 2013. A related review gets to know Andre in 1995.