Eyes on the City

John Haberin New York City

Marcel Storr and Keiran Brennan Hinton

Michael Gregory and Made in New York City

For an artist obsessed with cathedrals, Marcel Storr sure had his eyes on the ground. He had to, for he settled into a job as a street sweeper in Boulogne, and he never once left the city.

Besides, had he looked up, his visionary architecture would be gone. It has marked him as a folk artist, while Keiran Brennan Hinton follows consciously in the footsteps of one, James Castle. Hinton and Michael Gregory do justice to their subjects simply by imagining where they have lived. Can outsider art, then, find a home in the city, and are any of these truly urban or an outsider? "Made in New York" sees outsider art there all along. The show also opens with a pair of eyes.

One story at a time

Had Marcel Storr looked up, he would have had to turn away from adding floor after floor and detail after detail to his drawings. They never come close to adding up to a recognizable city or historical style, which is only his due. He may have loved them all the more for existing solely in his mind. He died in 1976 without an exhibition in his lifetime, assuming he ever sought one, and no one knows to this day how he stumbled on his visions. His earliest work, from the 1930s, sticks to more modest structures, although not the ones he knew. No works survive from another two decades.

Coincidence or not, Storr's imagination may have taken flight in middle age, in 1964, the same year that he took the job on the streets. Maybe he felt the need to escape its garbage and mundanity. Maybe, too, it taught him to worry over detail. Like Frank Lloyd Wright, he dreamed of grandiose unbuilt projects. (No, Wright did not complete his either.) Still, he recognized that even a mile-high city has to take things one awkward story at a time.

Storr conforms well enough to the outsider artist, in a gallery devoted to the like. He kept to a backwater compared to Paris, he had no skill in perspective or foreshortening, and he comes off as more than a little mad. Still, he was a visionary in a century of visionaries, and he bases at least one sketch on Rockefeller Center in New York. He had no interest in crossing over to architecture as a discipline, but then he came of age during Surrealism, with its dominion of the dream. His overwrought clouds, in art with hardly a single clear sky, have a touch of René Magritte. They also run to rust or blood red, from an artist equally fascinated with observation and what he could not see.

The show outlines four stages, with close to half of his sixty or so surviving works in graphite and colored ink. Early structures already include churches, even before they rise to a ridiculous scale. After street views, he tries higher vantage points, equally unnatural and designed to magnify the towers. They sprawl across outsize city blocks as well as vertically, and a fourth group could pass for urban planning. For all their plazas, though, they have precious room for air. The many indications of pedestrians, like those of beards, are preposterously small.

Boulogne does have a noted cathedral, but Storr seems uninterested in its commanding dome. He draws on many historical styles, mostly medieval, but he leans most to the spindly windows and towers of Gothic architecture—and with nothing so airy and stable as a flying buttress. And those peaks multiply out of control, too. He has something in common as well with the elaborate model cities of Bodys Isek Kingelez in Africa, but Kingelez constructed his from supermarket packaging, like Pop Art. Storr lives in a more distant and invented past. Like the skies, it also glows from within in unseemly yellow and red. He could well have had a horror of the present.

The show emphasizes the horror in its title, "Mysterium Tremendum" (with roots in terror as well as tremendous), after a critic, Donald Kuspit. Still, few will leave in fear. Like much outsider art, it seems more humorous, intentionally or not. Few, too, will agonize over details, by counting stories or the number of spikes or crosses emanating from any one tower. Even when buildings lean unsteadily, which is often, as in amateur photographs of skyscrapers, they seem in no danger of falling on those tiny specks on their steps—or on you. Storr would have shared in the elation.

Architecture's limits

No one would call Keiran Brennan Hinton an outsider. A Yale MFA graduate, he has settled in New York City, where he is on his second Lower East gallery and fourth exhibition in two years. He is also looking firmly about him.  Night scenes have the sophistication of a keen observer and of a twenty-something most at home in darkness and artificial light. The titles of those letter-sized paintings note the date and, at times, the weather, in a tradition going back to Impressionism. So why did he take off for Boise and a residency at James Castle House, its first?

Night scenes have the sophistication of a keen observer and of a twenty-something most at home in darkness and artificial light. The titles of those letter-sized paintings note the date and, at times, the weather, in a tradition going back to Impressionism. So why did he take off for Boise and a residency at James Castle House, its first?

If outsider art is now fashionable, with a featured room to itself at the 2019 Frieze New York, James Castle was anything but. He remained in Idaho, far from the art scene, until his death in 1977, and he occupied that house for longer than Brennan Hinton has been alive. It defined his life and his art, working with the small things around him. He is best known for his "soot paintings" on scrap paper, mixing his own saliva with soot and ink. The images might have fallen there or burned there. His deafness made him an outsider to others as well.

Castle's still lifes are imagined, while his frequent star shapes could well belong to a private language. He might have agreed with Ludwig Wittgenstein, the philosopher, that "the limits of my language are the limits of my world," although his only language was art. Yet they also show him obsessed with his immediate surroundings. For Brennan Hinton, too, architecture shapes an artist's life and art. Larger paintings stick to interiors, even in winter in the great northwest, and the walls press in, even as the outside floods them with light. Additional paintings on Hinton's return home adopt much the same format, subjects, and constraints.

He has not lost his powers of observation, far from it, but he does challenge the viewer's. Walls collide with furniture, set at equally sharp angles, and background spaces appear out of nowhere. Bits of wallpaper or paintings blend in with actual flowers, fruit, and everyday things. Colors, too, are both unnaturally harsh and familiar. Sunlight burns through a window and onto a wall, casting deep red shadows, while other areas run to blue and green. Their intensity flattens the fields of color, even as their shading attests to the real spaces that they inhabit.

They also attest to human presences and absences, including Castle's and his own. Drawers lie open and cabinet doors unhinged, as if recently abandoned or rummaged through, and a suitcase rests on the floor. Other paintings depict people as lumbering shadows, but drenched in still more colors and flora—as Giuseppe Arcimboldo in the late Renaissance and some Latin American art today. Titles speak of Here and There, suggesting both casual encounters and the opposition of here and elsewhere, and Penumbra. Another, as if objecting to his residency, speaks of his House Where Nobody Lives. They occupy a space between celebration and isolation, but then so does a city at night.

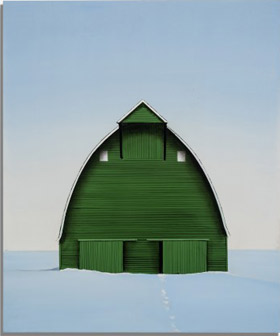

Michael Gregory, too, was a lonely traveler in a dark season. The small landscapes in "November's Guest" show barns in the Hudson Valley and New England, but they could just as well be in Idaho. Each structure stands isolated, one side parallel to the picture plane, amid wide-open spaces, dark clouds, or snow. Bare branches linger even amid the richest autumn leaves. Most of all, each boasts of a single white or color in contrast to the land, a bit like near-abstract houses for Eleanor Ray. They could be studies in architecture, color, or the artist's place in his chosen world.

Here's looking at you

Could F. Scott Fitzgerald have seen the eyes of E. G. Washburne? In The Great Gatsby, "blue and gigantic" eyes look down from a billboard, "out of no face, but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a non-existent nose. Evidently some wild wag of an oculist set them there to fatten his practice in the borough of Queens, and then sunk down himself into eternal blindness." Perhaps, but a shop sign for Washburne & Co. on Fulton Street looks anything but blind. It has acquired spiffy new light bulbs at that, thanks to the American Folk Art Museum, where it presides over "Made in New York City" and a lively urban history. Here's looking at you.

Subtitled "The Business of Folk Art," the show opens with not just the carved and painted wood, from 1915, but also a paradox: can the city, today a world capital of the arts, have ever been home to outsider art and outsiders? Surely folk art comes from folk traditions, rural communities, and madhouses. Think, though, of the stiffness of so much early early American portraiture, not excluding an AFAM favorite, Ammi Phillips. Think of an art newly apart from the academies of Europe, with the sophistication of John Singer Sargent or Thomas Eakins yet to come. Think of almost the entirety of the American wing at the Met.

Think, for that matter, of shop signs, weather vanes, and samplers, Currier and Ives, duck decoys, carousel rides, and quilting. The show has examples of them all, including a "Reconciliation Quilt" after the Civil War by Lucinda Ward Honstain, across from also a colorful silken bedspread by Samuel Steinberger. It reflects trends today, when folk art is big business and craft is often fine art. As the show's subtitle suggests, so they were in New York from the start. Woodcarvers and furniture makers had arrived from Europe, sure in their workshop training and eager to ply their trade, much as Steinberger had immigrated from Hungary. Portraits of all sorts and quality, too, found a ready market.

Artists and artisans played to the city, but they also described it. The curator, Elizabeth V. Warren, opens with the business of art in another sense—not the art business, but art about business. Unknown painters here depict glassworks, osytermen, and Wall Street. New York had bustling maritime industry, including a tradesman with the apt name Preserved Fish. Forty years before Walt Whitman wrote "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry," Robert Fulton got going with his ferry, cutting the travel time across the East River to minutes.

New York here seems quiet and even rural all the same. The bay off Brooklyn Heights looks idyllic, and the Manhattan skyline might as well belong to a small town. Canal Street still had its canal, with bridges. Later, Third Avenue had its train line and depots, but horses competed to the bitter end. Still, change defines a vibrant city, much as today. This is the kind of show one associates more with the New-York Historical Society than an art museum, and the society and the Met both contribute.

Art does sneak in, right under the eyes of E. G. Washburne. Portraits of the city's elders from before the revolution can look less folksy than ceremonious. Yet a young man with a squirrel on his shoulder, from a series of child portraits by John Durand, combines forced dignity with easy playfulness. The best-known painter here, Ammi Phillips, uses softer edges and paler colors for a greater sense of life. Shop signs come to life as well, with outsized gestures in three dimensions, like those of a mariner, a tea salesman, or the spectacles. Samuel Anderson Robb used a baseball player to advertise his own business in carving.

Is this the real New York, even in its time? Everything seems sunnier than it could ever have been. (A "reconciliation quilt" indeed.) And everything is caught up in the prejudices of its time, like a Chinaman for a tea salesman or a happy Native American for Robb. Folk art looks relevant in yet another way to American art now—in its very limits. Those eyes, Fitzgerald wrote, "brood on."

Marcel Storr ran at Andrew Edlin through December 8, 2018. Keiran Brennan Hinton ran at 1969 through June 16, 2019, Michael Gregory at Nancy Hoffman through June 8, and "Made in New York City" at the American Folk Art Museum through July 28.