Impressionism Unfinished

John Haberin New York City

John Singer Sargent: Watercolors

Drawings and Prints from the Clark

John Singer Sargent watercolors are dazzling, no more and no less. They are dazzling in their sunlight, at the Brooklyn Museum. This artist seems never to have seen a cloudy day. They are dazzling in their scope—from formal gardens to raging fires and from snow-covered mountains to blazing deserts. They are dazzling in their virtuosity. Who knew that watercolor could do so much more than brush lightly across paper?

When it comes to Impressionism, period, you may not think first of drawing. Suddenly painting could arise directly in response to light, one likes to think, with no intermediary but color itself. Now the Frick Collection, too, challenges that story, with a loan of just over fifty works on paper from the Clark Art Institute, in Williamstown, Massachusetts. "The Impressionist Line" makes a twofold claim, with line as the artist's most adaptable tool, but with a line of artists skilled in it from Degas to Toulouse-Lautrec as well. Through prints, it also helped a new painting find its audience.

Apart from Impressionism

One need not so much as enter the first room in Brooklyn to want to say it: Sargent could do anything. He would have been happy to hear it. He did, after all, earn a healthy living as a painter from dazzling others, as he did to Henry James, and he took pride in that. At the same time, he was turning fifty in 1906, a little weary of portraiture and pandering, aching to try something new. He used watercolors to push the limits of the medium and his talents—a medium for his sister Emily Sargent as well. He was out to surprise and dazzle even himself.

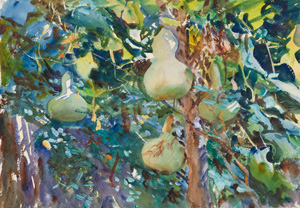

The museum would be glad to hear it, too. That is why it places three watercolors outside the first room, to get people talking. One from 1908 displays pomegranates against a network of green that snaps crisply into focus from barely a foot away. You have to remind yourself that color photography this bright was decades away. A second watercolor, from 1911, shows two women resting, their dresses spreading across the ground like a liquid white. Sargent was taking on the Impressionism of Luncheon on the Grass, of fashion and plein-air painting, as if he had created it.

The earliest of the three, from 1906, makes color itself a force of nature. An artist of high society was watching a wildfire. Only what I took at first for the distant fire was the Alps, breaking through the wildness to the sky. The tangled colors come close to inventing abstraction much like Hilma af Klint a good five years before František Kupka or Wassily Kandinsky. Maybe Sargent really could do anything, I wanted to say, or maybe (once gets over that initial rush of sensation) he looks that much the worse for trying. And that leaves open the question of exactly what he could do.

It was not realism or Impressionism, which is why it appealed to his friends the Sassoons, but something lighter and more dramatic than both. For a realist, Sargent has too little interest in detail and even less in labor. He moves easily among people, high and low, but in moments of boredom and rest. For a portrait painter, he has surprisingly little patience with psychology or appearances, and watercolors made him even more impatient. His subjects are not so much flattered by their dress as swept up in it, like a Madonna brought by angels to the heavens. Faces, when visible at all, have only their eyes.

As for Impressionism, he had neither the subject matter nor the technique. Where Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Renoir drawings, Claude Monet, and Monet in Venice gave expression to a new middle-class leisure, often their own, he preferred summers in the Alps. And for the painter who adapted Impressionism for Americans abroad, he all but eliminated its heart—the construction of space and light through color. He does not set pigments side by side, for optical mixing. He does not struggle to make sense of the visible, like Paul Cézanne and what a philosopher called Cézanne's doubt, or its incongruity, like Vincent van Gogh. Sargent washes colors into one another, alongside those dazzling whites, to get whatever hue, intensity, and darkness he liked.

The Brooklyn Museum takes pains to spell out his technique (also to be seen in the Eveillard gift to the Frick, a fine complement to the Eveillard gift of drawings to the Morgan library). It has ninety-three watercolors from barely five years, walls and walls of description, tubes of paint, and downright spooky videos of a hand at work, as if Sargent had returned from the dead to give lessons. He happily tried everything, so long as he ran the class. He wiped wet into wet and scraped it dry. He brushed wax across paper, taking advantage of accidental ridges to create marks as the wax later repelled watercolor—which he then worked up into a fuller composition. He embraced spontaneity while leaving nothing to chance.

Virtuosity and transience

What then was he doing, apart from everything? This artist transformed Impressionism into theater. Like a Romantic or even Frederic Leighton in a more Victorian climate, John Singer Sargent sought drama in color and light. He finds it in close-ups, of things closely cropped against a tense, dark, or indefinite background. One feels that one can grasp the pomegranates—or the row of urns on a ledge. While people in his watercolors do little or nothing, a marble statue of Daphne gestures like the singer in an Italian opera.

This theater's principal player is white. Sargent loves sails, dresses, and laundry hung out to dry. He loves the stone of Venice and the quarries at Carrara, his brush following their planes rather than dissolving them into color. He juxtaposes white with the white of the paper, and then he plays them both against walls of blue. In the canals of Venice, he seeks out the shadow beneath a bridge. Mist fills the gaps between mountains and clouds, and one might wonder if one ever sees the sky.

Sargent's sense of drama could make his eye too quick and his art too superficial. Maybe he was no more than dazzling, and no less, and museums have chafed at his slick reputation ever since. The Frick Collection and Boston's Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum exhibited his late landscapes in 1999, and Brooklyn tackled his portraits of children in 2005. It argued for undercurrents of adult anxiety—and maybe even a hand, as with Francisco de Goya and his Red Boy, in the invention of childhood. The Met included him in 2003 with "The French Taste for Spanish Painting," a reminder of both his place in the avant-garde and his eye on the past. He recognized the dilemma himself, when he set aside portrait commissions for watercolors.

If he never got over his love-hate relationship with his time, maybe the restlessness began with his origins. Born to Americans in Italy, Sargent trained in Paris before moving to London in 1886, but he never did settle down. His watercolors show him back Italy and France, in Portugal, and in Syria. He summered in the Simplon Pass in (yes) the Alps. Hoping for a mural commission for the Boston Public Library, on the theme of the Sermon on the Mount, his first instinct was to head for Palestine to get it right. When it comes to Venice, he thought first of the canals, and when it comes to the North Africa and the Middle East, he thought first of sailing ships and Mediterranean ports.

If he never got over his love-hate relationship with his time, maybe the restlessness began with his origins. Born to Americans in Italy, Sargent trained in Paris before moving to London in 1886, but he never did settle down. His watercolors show him back Italy and France, in Portugal, and in Syria. He summered in the Simplon Pass in (yes) the Alps. Hoping for a mural commission for the Boston Public Library, on the theme of the Sermon on the Mount, his first instinct was to head for Palestine to get it right. When it comes to Venice, he thought first of the canals, and when it comes to the North Africa and the Middle East, he thought first of sailing ships and Mediterranean ports.

As he traveled, he was drawn to Bedouins, soldiers, and day laborers—in other words, to transients. When he sketched his friends, he drew them as tourists and as artists. Paul Helleu, known to New Yorkers for the ceiling constellations in Grand Central Station, is even painting while in a boat. This is not so much art about art as art about seeking. More than once, the artist is in the middle distance instructing others. In contrast to the male hierarchies of his time, when even Edouard Manet poses Berthe Morisot as a model rather than a painter, at least one such artist is a woman.

The Brooklyn Museum wants you to know how close it was to the avant-garde from the start. It bought a little under half the sheets from Sargent's first show in New York, at Knoedler in 1909, and Boston's Museum of Fine Arts snagged the rest in 1912. It is startling how new they were then—and how new they become now, to the point that the occasional painting hung with them looks rigid by comparison. They will not alter his reputation, so much as make one see artists as already tourists, in their appreciation for surfaces. Sargent traveled the world to get the facts, and he found to his delight more surfaces. His limits start with how deftly he passed from accomplishment to experiment.

Impressionism's lineage

Most people think of Impressionism as about as close as art will ever come to natural. Where Surrealism introduced automatic drawing, Impressionism can seem a kind of automatic painting, driven by nature rather than unconscious desires. For a more sophisticated audience, it brought art that much closer to Modernism by battling two traditions—academic training and Romanticism's ego trip. From Monet to Cézanne, it sought the essence of art by working out the same themes on canvas over and over, from waterlilies to card players, until the whole idea of originality in art changed its meaning. No wonder the Met sells tickets by making Henri Matisse say, "I never retouch"—although Matisse painted over an entire painting of his studio in red.

Okay, you know better than that, but you may still find a stunner in Monet's 1883 view of Rouen or a fishing village in Normandy, from 1864. Both deal with stillness rather than transience, and both use chalk for its economy. In the first, a few loops takes care of the shadows of a boat on the water or the reflection of the town. In the second, a single zigzag suffices for each cloud. Apparently, if one wants to deal with pure color, one had better keep it clean. Berthe Morisot does something similar with another harbor scene, where a wash dissolves a mast to capture sunlight, but also so as not to distract from the boats, their green shadow on the water, and the gentle motion it implies.

Monet's loops and zigzags had another point as well, as preparation for a print—the elements for photomechanical transfer to zinc. The show includes a range of media that brought prints closer to painting, such as lithographs, aquatints, and monotypes. Artists may not always have made preliminaries to painting, but they did take steps from painting to the public. The new art's appearance of spontaneity, the Frick insists, actually increased the demand for prints and drawings. Camille Pissarro boasts of his lack of finish when he signs and dates a pastel. Manet is most polished with his Execution of Maximilian because he wanted its 1868 coolness and outrage to find wider distribution in 1884.

The Frick does not say so, but the discovery of Dutch art also helped to blow academic and Romantic norms out of the water, while creating a market for prints. An etching by Manet quotes Rembrandt (as well as Jean Antoine Watteau), with frank attention to the bather's lack of youth and beauty, much as in the drawing here by Paul Cézanne. Dutch genre painting also influenced Jean-Francois Millet's ode to labor, his Sower, where the visible hairs of a brush in the pastel clouds makes a nice contrast with the regularity of the Conté crayon earth. Markets were growing, too, as robber barons entered them—and paved the way for small museums like the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute and the Frick. Their partnering is a useful alternative to museum blockbusters, like Impressionism and fashion at the Met. The Frick also borrows from the Clark for its concurrent show of Piero della Francesca, much as it partnered before with the Norton Simon Museum and the Courtauld Institute.

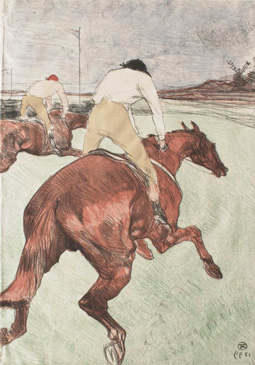

Any study of line has to give space to Honoré Daumier, Edgar Degas, Degas prints, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Daumier mixes media for the greater darkness, to join drinkers or lawyers in a huddle while they slurp or converse. (Monet, believe it or not, left a caricature as well.) With Degas's virtuosity, studies from life came to mean far more than the classical nude. Even sketches after sculpture in the Louvre add the tension of real musculature, the illusion of a model caught lounging, and reflections off the glass case. Horses have multiple legs, in search of perfection and in line with photographic studies of motion.

Daumier made it to the track himself at the end of his career, in 1899. With the forced perspective, the repeated flagpoles, and the jockey's butt raised high, Impressionism is giving way to something stranger. His seated clown's ambivalent gender and wide-open legs have their unconscious in a couple's tryst at left, while Loïe Fuller, the dancer, approaches abstraction. As one last plea for prints, Paul Gauguin returns to the oldest and clumsiest of them all, in Gauguin's woodcuts, for his primitivism. The dashes of his 1889 Old Women of Arles, actually a zincograph (an early approach to photogravure), suggest both a ghoulish ritual and an etching. His Breton Bathers is like stepping into a cloud—and into the twentieth century.

John Singer Sargent watercolors ran through July 28, 2013, at The Brooklyn Museum, "The Impressionist Line from Degas to Toulouse-Lautrec: Drawings and Prints from the Clark" at the Frick Collection through June 16.