Changing the Channel

John Haberin New York City

Revolution of the Eye: Modern Art and TV

Stan VanDerBeek: Poemfield

Think you know your TV? In 1966, for Color Me Barbra, a CBS special taped Barbara Streisand in outlandish but forgettable clothing and accessories, slinking backward around the Philadelphia Museum of Art while belting an outlandish but forgettable pop song. Now ready? Choose:

(a) The new medium drew its form and content from modern art.

(b) Streisand can turn her back on Cubism with the best of them.

(c) Both sought the cultural legitimacy of art but little more.

(d) Can I please change the channel?

If you answered (a), you will appreciate "Revolution of the Eye," an ingenious history at the Jewish Museum. A postscript picks up the story with films by one of the show's contributors, Stan VanDerBeek.

Bad day at Black Rock

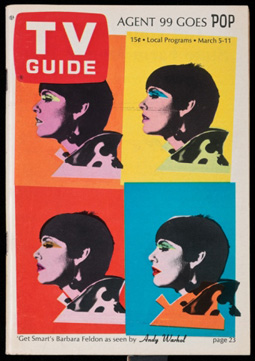

Subtitled "Modern Art and the Birth of American Television," it follows the medium as it became a dominant force in advertising and the American living room. And the museum traces that dominance to creative minds steeped in Modernism and the analog city. Television and video have had many golden ages, not least today, and the show ends with Andy Warhol on Saturday Night Live in 1981—hailing a cab in Astor Place while leaving his head indoors on the floor. Andy Warhol has a whole room in a large but otherwise one-room show for his appreciation of such TV icons as Groucho Marx and Get Smart, not to mention a woozy commercial for Schrafft's ice cream. Yet its heart is in the 1950s and 1960s, as TV sought models for its stark, grainy black and white and then its explosion of color. As a famous voice intones, you have entered the twilight zone.

Obviously artists in those same years were turning to popular culture, both for inspiration and for something to take apart. Warhol's Jackie could not have had her allure without it. The exhibition opens with photos by Lee Friedlander of TV sets, with eerily cropped faces and eyes. Still, its core narrative runs the other way, with the influence of art on TV. Even without Friedlander, it argues, the tube would have looked downright surreal. That same cropped eye appears on a metronome for Man Ray in 1923, as Indestructible Object—and it found a new role as the logo for CBS.

CBS is the show's touchstone, especially in its first half, although it turns out to owe the eye less to modern art than to the Shakers. The network's designers included Ben Shahn, with strikingly spare weaves of black lines, and Georg Olden, an African American. Eero Saarinen designed Black Rock, its towering New York headquarters, right down to the chairs. Under William Golden and later Lou Dorfsman, they were fashioning not just programming and advertising, but a corporate identity. William Paley, the chair, collected art and served on the board of the Museum of Modern Art. In turn, MoMA took an early interest in TV—from a short-lived Television Project in the early 1950s to Television U.S.A., a look back at thirteen seasons in 1962.

The curator, Maurice Berger, knows something about museum engagements with television. He works at both the University of Maryland's Center for Art, Design, and Visual Culture and the National Jewish Archive of Broadcasting at the Jewish Museum. Who knew it even existed? Yet Paley, along with so many show-biz greats, was Jewish, although plenty of others were not. Berger's open layout, with over two hundred fifty objects and clips grouped by frequent wall text, may look more like a video catalog than an exhibition, but it is not unmanageable. If anything, for once, clips are too short.

The show's provocation lies in their parallels to art. Could Rod Serling's opening to The Twilight Zone rework the second Surrealist Manifesto by André Breton from thirty years before? Could spinning circles copy 1935 Rotoreliefs by Marcel Duchamp. Could a door to the mind and to space pick up René Magritte? A set design for Dinah Shore multiplies skulls out of Georgia O'Keeffe and O'Keeffe drawings. Ernie Kovacs captures the terrors of Surrealism in his routines, too, and he was a comic.

Could such programming as Of Black America with Bill Cosby pick up on social realism? Apparently Cosby did not play only the cuddly father figure. One also gains a greater appreciation for early TV's harsh visual contrasts between black and white. Even the clumsiness of pixilation looks more artistic, rather than a pale echo of oil on canvas. Dorfsman's streams of ever-changing letters anticipate all sorts of text art. As an ad from Shahn insists, "look closely at your horizons."

Art's hullabaloo

Already, though, one may have doubts. Start with the sheer gulf in time between supposed influences and TV. Could all this represent nothing more than the eventual mainstreaming of the avant-garde, as with "Signals" at MoMA? CBS sure went about merchandising that corporate identity, with cufflinks and ashtrays of the eye. Boots based on Piet Mondrian appeared on Hullabaloo, of all places, much as Yves Saint Laurent was marketing a Mondrian dress. As a character in MoMA's video project has it, "If I can't be an artist, I'll be a millionaire."

CBS sold paint kits for kids, for vinyl "magic drawing screens" that adhered to the TV set, to accompany Winky Dink and You. Stan VanDerBeek, the experimental filmmaker, served among others as animator. Still, "connect the dots" games have a long way to go to inspire the "modernists of tomorrow." No one doubts the existence of educational programming either, but so what? Aline Saarinen on NBC introduced Americans to such modern artists as Edward Hopper and Alberto Giacometti, but then she wrote for print as well. Besides, the subject of arts programming did not begin and end with Modernism.

The parallels become that much more tenuous in the age of color. Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In belongs to the psychedelic era, but it hardly needed a push from art. ("Sock it to me.") Bonnie Maclean's posters recall Peter Saul, but they were for the Fillmore East, not television. It takes an even greater imagination to link stage sets for Ed Sullivan to Minimalism, including models for the Jewish Museum's legendary show of "Primary Structures." It also takes ignoring Minimalism's disdain for saturated color and flashing lights.

The show's cleverness and depth are still a revelation—and a great deal of fun. They will also stir no end of nostalgia in those of a certain age. One can date oneself by what one remembers. Their value, though, may lie not so much in the narrative as in unsettling old stories about art and culture, high and low. Fernand Léger had his influence on Serling with Ballet Mécanique, but this was not classical ballet. Willem de Kooning, with a cigarette, looks right at home in an interview on TV and Salvador Dalí on What's My Line.

Which came first, television's chicken or art's egg? Which was the ghost in the machine? Batman looks right at home next to Roy Lichtenstein (Pow!), but both start from actual comic books. Allan Kaprow had his "happenings" in 1959, embraced the invention of the Sony Portapak in 1967, and accepted a commission from public television with Otto Piene. Check out an old TV in wood, and one may want it for one's private collection. Check out a white floor slab, from Robert Morris in 1966, and one may want to get up and dance.

The problem of disentangling creativity and commerce is all the more relevant now, when art is big business. As Duchamp said on TV even then, "There's no more shock anymore." Maybe Serling could still hope to shock, but opening credits for Playhouse 90 by Saul Bass never made it on the air. Arts programming was a calculation all along, targeting women because men just "were not a significant audience." As for fine art, was Andy Warhol simply continuing his career as commercial designer, attending church, or forging the ultimate avant-garde? Art being what it is, the jury will always still be out.

Pixilated fairy tales

Coming to Stan VanDerBeek from the Jewish Museum, one can hardly help thinking of television. The museum's "Revolution of the Eye" claims a lot for the medium. Not only did it draw on existing art for imagery, including classics of Modernism. It even hired VanDerBeek to help design cartoons. Already in the 1950s, well before Paul Sharits, the experimental filmmaker was, literally, asking kids to connect the dots. And here you thought Rocky and Bullwinkle were subversive.

Could he, in turn, have had TV in mind when he returned to his art? From 1966 to 1971 he set to work on Poemfield, with its poetry and its visual field alike as pixilated as a cathode ray tube (and a later show including his daughter is called "Photo-Poetics"). He in fact projected it onto one before filming the results, each step both enhancing color contrasts and further distancing design from lived experience. Pixels fly by, with the pace of the television era or his own Movie-Drome, now and then shaping themselves into words. Now and then, too, one can even read them. Who said that Nam June Paik had new media to himself?

Could he, in turn, have had TV in mind when he returned to his art? From 1966 to 1971 he set to work on Poemfield, with its poetry and its visual field alike as pixilated as a cathode ray tube (and a later show including his daughter is called "Photo-Poetics"). He in fact projected it onto one before filming the results, each step both enhancing color contrasts and further distancing design from lived experience. Pixels fly by, with the pace of the television era or his own Movie-Drome, now and then shaping themselves into words. Now and then, too, one can even read them. Who said that Nam June Paik had new media to himself?

The gallery projects five of the project's eight parts on four walls, thanks to the artist's estate, in art all about excess. Poetry here, in its own words, is better and a product of loves, but also suspect. Like those early cartoons, the series is enthusiastic but subversive, thanks in part to its disconnections. Think of Jay Ward's "Fractured Fairy Tales," but without a story line. VanDerBeek was not designing for children this time, but the tumbling pixels do look like early computer art and early video games. The artist, who died in 1984, would never have known more sophisticated ones.

He really was thinking in terms of animation—but not at all about TV. He was working between MIT's Center for Advanced Visual Studies and Bell Labs in New Jersey, where Ken Knowlton was developing BEFLIX, one of the first programming languages for computer animation. The programmer's last name slips past, as one of the work's more cryptic messages. This was computer art long before the New Museum had its social-media triennial. His collaborators also included John Cage and Paul Motian, the jazz drummer and composer, although the soundtrack sounds more like the ordinary rumble of a science lab. The avant-garde then sought to be explicit and self-reflective, if also difficult, and VanDerBeek sought to give credit to all he had learned, but maybe he liked, too, that the text thus holds the word know.

Not that associations with television vanish altogether. If nothing else, as poetry Poemfield is pretty boring. It does, though, hint at how much television and computers then had in common. Both were clumsy, and they shared the same monitor. Segments here begin with the second-hand countdown of old TV. They also look very different from the slow pace and murky backgrounds of experimental film for Andy Warhol, Bruce Conner, or Michael Snow.

The show might give heart to fans of the Jewish Museum or of his enormously talented daughter, Sara VanDerBeek, but not entirely. Yes, television was subject to experiment—and still well ahead of desktop computing. Artists, though, were taking their business elsewhere, including those like Warhol and VanDerBeek who had worked in TV. Their experiments would not have found space there, and they were not, for all critical complaints about Warhol, looking for its mass audience. Minimalism had triumphed, as with VanDerBeek's geometric graphics, and field itself belongs to the vocabulary of color-field painting. At its best, Poemfield is all about color.

"Revolution of the Eye" ran at the Jewish Museum through September 20, 2015, Stan VanDerBeek at Andrea Rosen through June 20.