3.14.25 — Confronting the Klan

The War to End All War did not end war, and the Holocaust did not put an end to anti-Semitism. Racism in the United States has its own ugly history as well. Can a contemporary black artist and a Jew from another era face it together?

The Jewish Museum opened its latest show the day after Donald J. Trump’s reelection with an archival image of a lynching. Both Trump and the lynching drew larger numbers than I ever imagined. Draw your own conclusions.

The Jewish Museum opened its latest show the day after Donald J. Trump’s reelection with an archival image of a lynching. Both Trump and the lynching drew larger numbers than I ever imagined. Draw your own conclusions.

A video cuts between the grainy photograph and still another spectacle—a carnival in Paris, Texas, where the black man in the photo suffered a grisly death. It lingers over colored lights and rides, with the cutest of animals as their seats. It lingers even longer over the moment before death. Nor is it the only image of a lynching in “Draw Them In, Paint Them Out,” where Trenton Doyle Hancock “confronts” (as the museum has it) Philip Guston through March 30. Guston began drawing the mob nearly a hundred years ago, when its threat was all too real. Hancock to his delight is still catching up.

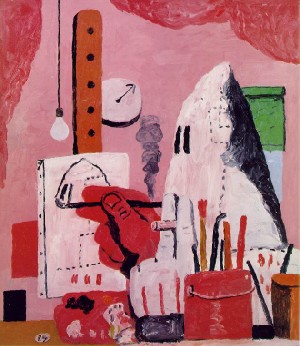

Born in 1913, Philip Guston has become a gallery and museum staple for his images of the Klan, including himself in his studio with blood-red hands and a white sheet over his own head. At first he earned anger and disdain for his turn from the comforts of postwar abstraction, later, as his fame grew and “mere” cartoons became fashionable, for his subject. Only recently Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts came close to canceling a retrospective, opening at last without a black curator. An African American, Trenton Doyle Hancock is still based in Texas and still grappling with the same sense of guilt and the same fears. He was not even born when Guston returned to that theme in 1969, but the Ku Klux Klan haunted him from an early age as well. One can still ask just who is confronting whom.

Guston’s early drawings have a nasty realism, Hancock’s a loaded ambiguity. In a photograph, he lies on his back in a corner completely covered by a sheet. He could be a dead body left for disposal or a Klansman catching up on sleep. Guston’s later figures are closer to caricature, with a nose borrowed from Richard Nixon. Often he sets just two figures side by side, as the artist and his model or the racist and his victim. He may never have left the studio for all one knows, but it is scary enough inside.

Hancock has much the same pairings, but with a recurring hero, named first Loid and then Torpedoboy. The character is at once captive and superhero. He is also both a participant and an observer. He may turn white from shock, far whiter than the murderer, or pitch black as if seen through the white man’s eyes. He also has more colorful pop-culture scenery, like the fair grounds. Paintings get much of their colors from plastic cups and lids. In ink on paper, dialogue or commentary runs wild without offering a pat resolution.

The controversy is not just about putting a good face on black experience in today’s culture-affirming art. It is about who has the right to speak for whom. Born in Canada to Ukrainian Jews, Phillip Goldstein grew up in LA from age 6. His parents had found safety and must have hoped for, well, normalcy, but he never could. You will recognize the turn against him from the 2017 Whitney Biennial, where a white artist, Dana Schutz, dared to paint the open casket of Emmett Till. They were taking responsibility for what they fear most.

Black artists, too, face their share of shoulds and should nots. Kara Walker has had no end of complaints for appropriating stereotyped black silhouettes. Should an artist paint only what she sees in the mirror, and should a male novelist incorporate only men? Should art stop speaking out against bigotry? I sure hope not, and I appreciate the sheer cacophony of voices at the Jewish Museum from just two artists. As Hancock has it in a recurring title, Step and Screw!

I have written way too much elsewhere about Guston, at the Met and in Chelsea, but then this is Hancock’s show by far. Yet the more time he spends on Guston, pouring through the estate in preparation for this show, the closer he feels. Did Guston paint a ladder to the sky, as his approach to memories? Hancock’s hero thrusts one leg through a ladder of his own. His are big canvases and maybe a bit silly, and I cannot tell the show’s four themes and sections apart, but daring and controversy go a long way. As a Jew in my own way myself, I can feel the mob growing closer and the spectacle all too real.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.