Talking Dirty

John Haberin New York City

Bruce Nauman

Bruce Nauman has got MoMA talking dirty, over a full floor plus the entirety of MoMA PS1. Will he ever clean up his act? The museum may hold out hope, for what it calls his "Disappearing Acts," but I am not holding my breath.

The Web site for his mammoth retrospective cannot lead with the naughty bits. (Who knows who might be looking?) Still, the Modern uses Pay Attention as the cover image for its press materials, and the lithograph has pride of place in Queens, facing out from the entrance wall of the main gallery on the second floor. I shall leave its concluding text as MOTHERS in deference to family values. The smeared, jagged lettering in black and white and the thick black underscore for every word only rubs in its point: this means trouble, and this means you.

Zen mother

In asking you to pay attention, Bruce Nauman is not just guilty of egotism, sexism, and name-calling, although he is surely indulging in them all. He is also insisting on what decent art always does—to get you noticing what you had never seen before. He has described his work as about "what is overlooked," and indeed the print reads backward, to insist that one look twice as hard. At the very start of his career, between 1965 and 1968, he made a cast of the space beneath his chair. If it, too, had the brutal edge of a concrete slab, he can sound downright mystic in his call for attention. One might call him the Zen mother.

For MoMA, he is shouting less these days and contemplating more. If that sounds awfully unlike him, he earned his reputation as a provocateur the hard way, by making life difficult even for his fans. He even employed industrial fans to help. They blew cold air on the audience for the Merce Cunningham dance company in 1970. An audio file two years earlier put it bluntly, as Get Out of My Mind, Get Out of This Room. A steel cage from 1974 nested tightly within a second cage, even with its door open, offers little hope of entry or release.

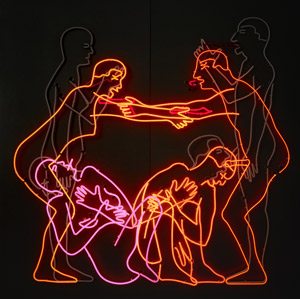

Nauman makes an art of torment, not least with a 1987 video, Clown Torture. The performer in clown makeup and costume cannot stop screaming—unless you count a second channel, where he reads while on the toilet. Drawings outline a hanging and a Punch and Judy show, as Crime and Punishment. Slim neon tubes blink on and off for the figures in Sex and Death by Murder and Suicide. Sex and death together are, it suggests, always on his mind and, he presumes, yours. An early video has a long fluorescent tube between his legs, as an impaling or erection.

Language for him is inseparable from both the torment and the ambiguity. More blinking tubes alternate between life and death, love and hate, pleasure and pain, while another lithograph declares itself or maybe you dead. So, too, is music. Nauman started as a musician, accomplished enough that the Grateful Dead slotted him as an opening act, although he refused in the end to perform after still earlier acts reduced his time slot. One might never know it, though, from a full hour in 1969 repeating a single dissonant strum—with the violin tuned to D.E.A.D. As more neon declares, you had better expect the conjunction of violins, violence, and silence.

Is there something uniquely American in the obsession and the violence? Is there something uniquely male? One can see more than fifty years now of Nauman's art as one long macho posturing with little room for silence. Female collaborators are rare, although a two-channel video from 1985 pairs a young black male with a prim, demanding white woman as Good Boy Bad Boy. The artist had already left New York in 1979 for a remote spot in New Mexico, halfway between Santa Fe and Albuquerque, where in time he resumed performance in a cowboy hat. One video has him training horses.

The link of coercion to animal training gets at another running theme of his art. If humans for him are essentially male, human nature is essentially animal. And if torture here is in any way objectionable, so is the human treatment of animals. Nauman started casting in the late 1980s from taxidermy animals. Eyeless dogs in a spinning carousel hang by their necks, while caribou form a creepy pyramid. A rat in a maze paired with loud incessant drumming present two models of learned helplessness.

You try my patience

Born in 1941, Nauman is a gallery and museum fixture—the man who cast aside painting because, he said, "whatever I was doing was art." He joined in the opening show at P.S. 1 as a center for contemporary art in 1976. Not everyone, though, is a fan, industrial or otherwise. Critics of a MoMA retrospective nearly twenty-five years ago could not agree on whether he was too monotonous, too shrill, and too male or too all over the map. His many obsessions and media open him to both views. Well before Paul McCarthy, Mike Kelley, and Mike Bouchet, he was art's original bad boy playing in heavy traffic.

MoMA, though, would disagree, seriously. It sees his art as a lifelong act of contemplation. It sees a Zen disciple even in a cowboy hat, building a fence on video for thirty seconds short of an hour in 1999. "If this fence is going to last," he tells himself, "it has to be done well." Two years later, he invites one into his studio at night for nearly six hours on seven channels. If you hang around long enough, you might notice field mice and goodness knows what else.

The retrospective plays down the bad boy by assigning Clown Torture a small room on the second floor at MoMA PS1. It also sees recent work as a deepening contemplation and a decrease in volume. As early as 1968, he took on Renaissance sculpture with its contrapposto, or quarter turn at the waist, by shimmying his way between Sheetrock walls. By 2015, the narrow passageway has opened up. A video multiplies his Contrapposto Studies over seven walls of color and eight times as many images of Nauman—half in white pants and a dark blue shirt, the other half the reverse. One last Contrapposto Split has him back in his studio, slightly staggered in space and time at the waist, all the roomier for the view through 3D glasses.

Perhaps, but fences keep people or animals in or out, and this one was on his property. Mapping the Studio can seem an interminable view of emptiness and trash, and a subtitle throws in a dig at an icon of repetition and silence: Fat Chance John Cage. No cow is too sacred for Nauman, not even John Cage. And those studies of his body in motion keep coming, in three successive rooms, just when you thought that you were done. If they do not try your patience, nothing will.

Surely that is the point. When a stuffy man complained, "You try my patience," Groucho Marx had his answer ready: "You must come over and try mine sometime." Nauman offers much the same invitation, year after year. You can take small comfort in that he edited down the several hours of Mapping the Studio from months of infrared camera footage. You might even grow to like it—or not.

Surely that is the point. When a stuffy man complained, "You try my patience," Groucho Marx had his answer ready: "You must come over and try mine sometime." Nauman offers much the same invitation, year after year. You can take small comfort in that he edited down the several hours of Mapping the Studio from months of infrared camera footage. You might even grow to like it—or not.

The retrospective, too, asks for patience. Just months ago, Adrian Piper took the whole of MoMA's sixth floor—the first time ever for a single exhibition or artist. Nauman gets not just that, but a whole other building as well. One might start in Long Island City for the big picture, ending in midtown Manhattan for a room of early sculpture and a vast space for a few large installations. Even the curatorial team has grown to five, led by Kathy Halbreich, who also worked on the 1995 show. They place work not chronologically, but pretty much wherever they like and wherever it looks good.

Sarcasm or ambiguity?

It may never satisfy critics, me included, but it offers a fuller picture and that opening up. An interactive video at MoMA PS1 draws you into narrow passages—first with a view of your back on a monitor at the very end, another with the view in front of you at your feet. It connects to contemporary concerns for surveillance video, as with Eckhaus Latta at the Whitney. And then a work at MoMA follows you in a wide-open space, rounding a Sheetrock corner. A final audio, on flat speakers suspended at eye level like Minimalist sheets, exchanges the curse words for the days of the week.

Maybe Nauman is not so self-involved after all, or so MoMA hopes. His "disappearing acts include not just his escape to New Mexico. One cannot easily pin him down behind the clown makeup and the contrapposto. Could even the macho posturing be a pose, and could the constant exercise in futility pierce it once and for all? Is the clown screaming at you or only in pain? Ambiguity runs through all the text art as well, in the opposition of life and death or, in limestone from 1984, the seven virtues and the seven deadly sins.

Maybe, but irony extends only so far. Neon for The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths leaves no doubt who is smugly laughing at whom. Two industrial sinks from 2007 serve as fountains, a supplement after forty years to the obvious sarcasm of a work on paper, The True Artist Is an Amazing Luminous Fountain. Well, O.K. For all the confrontations, Nauman can never match the punch of Piper's assaults on art and racism. Where she is speaking truth to power (meaning, again, you), he is speaking truthiness to poverty.

When it comes down to it, Nauman has not added all that much since his call to pay attention in 1973. He just returns to older motifs as best he can. And yet the show works, because all the repetition keeps it together while the confrontations keep it surprising. The relative lack of punch also makes a huge show manageable. One can breeze through MoMA's top floor, gratefully. (Who knew that it could tear down all those walls?) The show also brings out his place in and apart from his time.

Like Robert Rauschenberg, he collaborates with dance and picks up where Marcel Duchamp left off, with Fountain as urinal, but he is still spouting off. The taxidermy pyramids also resemble Duchamp's bottle rack. Like Robert Smithson and earthworks, he accepts entropy enough to affix a work to a tree, so that vegetation will grow over it in time—but it was text (quoting Ludwig Wittgenstein) and never fully a part of nature. Like Michael Heizer in Texas, he works in seclusion, but without the pompous scale. He has his hard sculpture like Minimalism without the form, his soft materials like Joseph Beuys but with every taste of disgust, his sardonic text art like Lawrence Weiner or Mel Bochner but with the jokes more plainly at everyone's expense except his own, and the physical side of conceptual art but never altogether free of aggression. Static video or film has a parallel in Andy Warhol, but with a greater challenge to one's patience.

What you think of it all may depend on what you make of the irony. How anodyne is a country music riff on Dobro and pedal steel as The End of the World? Does the impress of his body in foil, felt, plastic, foam, and grease or the reduction of his shoe to an inedible black goo amount to self-denial or self-satisfaction? He can seem blissfully accepting, as with the cast of his chair long before the negative spaces of Rachel Whiteread, or just plain disgusting, but always with a healthy lack of sentiment. I shall never forgive him for the posturing or the bad boys that came after him. I can thank him, though, for getting a major museum down and dirty.

Bruce Nauman ran at The Museum of Modern Art and MoMA PS1 through February 25, 2019.