So Well Timed

John Haberin New York City

Peter Campus and Gary Hill

For some, video art is a natural—a way to situate people and images within real time and space. For others, it is a way to mix things up, thanks to no end of editing tools.

For still others, it is a way to root art in a culture of images. For some of its pioneers, though, all it takes is the camera to disorient its subject and viewer. For Peter Campus, it scrutinizes real people and places, but at a cost to both. For Gary Hill, at a gallery long dedicated to interactive art and new media, it is thoughtful, rigorous, and downright scary.  It may not scare viewers half as much, but it should get them thinking, too.

It may not scare viewers half as much, but it should get them thinking, too.

So I see

Peter Campus abandoned video in 1978, in favor of outdoor photography, and one can see why. It must have come to seem confining, and no one did more to make it so. He shot himself in performance up close, as if unable to move. He shot himself walking alone in a tunnel, in a lane normally reserved for cars, as if unable to escape. He shot himself from above, as if pinned to the floor, and overlaid with multiples of himself or just plain white noise, as if dissolving into another being altogether or nothing at all. Wait long enough, and the static subject often did shift to another performer.

Perhaps the whole performance scene had become confining. Campus meanwhile had moved closer to nature, on the South Shore of Long Island, where he could hold bits of nature in one hand. Then, too, one can see why he took up video once again in 1996, for what he now calls his videographs of Shinnecock Bay. Still images of small things must have fallen far short of the evidence of his senses. "Video Ergo Sum," a modest retrospective at Bronx Museum, identifies him with the medium itself, but it means something simpler and grander in Latin: I see, therefore I am.

He is training others how to look as well. Now that video is digital and capable of incredibly high definition, Campus exploits those two facts as facing extremes. At his gallery, one projection is highly pixilated, daring you to make out the changing scene. Another shows a man slowly reeling in a fish, but the creature's sharp orange might have dropped into the picture from a cartoon or another world. The artist's early black and white conjures up bare-bones memories of a performance space like the Kitchen in New York City, just when TV itself had moved to color. Now he relishes the light.

One can see his pleasure in the literalism and poetry of many a title, with thoughts of the stillness of winter, dusk, or at rest. And Campus has appeared in a retrospective of early video called "Into the Light." In one video, the very pixilation transforms the side of a barn or home into blocks of near white—much like a Shaker meeting house for Mariam Ghani and Erin Ellen Kelly. At the same time, he treats a frozen image as a disturbance. A rill through a marsh, leading to the water's edge, is A Tear in the Fabric, but he could be speaking about his art as well. The high res invites you to linger over the texture of seaweed or the crests of the tide, while the distortions invite you to linger over what nature has become.

His is an art of both contemplation and disturbance, but so it was all along. An early work reflects you, the viewer, back at yourself, so that with every twist and turn you feel less and less able to turn away. The hidden camera comes into the light, right on top of the monitor, but its surveillance continues. Yet it also shows the space and others behind you, at ease in the present. It accords with the Minimalism of its time, in what Michael Fried derided as theater—but also in daring you to turn away from the object, here the monitor, to experience the room. The largest of early close-ups even anticipate the later acceptance of anxiety as the fabric of life, with Head of a Man with Death on His Mind in the Bronx and Head of a Sad Young Woman in Times Square.

Another survey, "Talent Show," placed new media in context of Andy Warhol, who had his own thoughts of stillness in regard to the Empire State Building. In his isolation on camera, Campus also resembles Bill Viola, Bruce Nauman, and Sophie Calle—but without their theatrical excess, confrontations, or confessions. His Latin suggests early video's philosophical side, too, in Gary Hill. Yet he meditates more on transitional spaces, the kind that can hold an image seemingly forever before leaping to another. In two samples at the 2019 art fairs, one could almost make out houses and fences along the bay, and other video hones in clearly on industry. They mark transitions between an escape to nature and its human disturbance.

The philosophy of art

Gary Hill must be the most philosophical of living artists. He knows how hard it is to make sense of even the most everyday experience or to justify even the most everyday conclusions. He knows, too, the price of failure and the need for trying. For thirty years, he has brought the awkwardness of perception and the perceived to video, philosophers to the soundtrack, and the gaps between them to the viewer. His latest show takes the components into three dimensions, as interactive art and installation. The very gaps have become tactile as well as audible and visible, as "On the Outskirts."

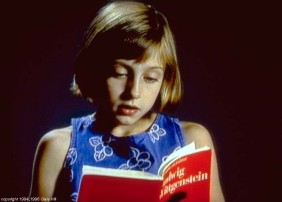

Hill did more than anyone to give new media their present shape. Nam June Paik with his boxy TV sets, magnets, and picture tubes created video art in a time of performance art, assemblage, and suburban living rooms—in collaboration with Charlotte Moorman on cello. Hill, with such artists as Bill Viola and Peter Campus, brought it into the 1990s, a time of skepticism, algorithms, and tarnished images. When a little girl reads aloud from Ludwig Wittgenstein's Remarks on Color, is she heroic, comic, or touching? When homeless men stand against a dark wall, like a police lineup allowed freedom of motion, are they under scrutiny or are you? You may find your own answers, but philosophy is all about the questions.

Hill did more than anyone to give new media their present shape. Nam June Paik with his boxy TV sets, magnets, and picture tubes created video art in a time of performance art, assemblage, and suburban living rooms—in collaboration with Charlotte Moorman on cello. Hill, with such artists as Bill Viola and Peter Campus, brought it into the 1990s, a time of skepticism, algorithms, and tarnished images. When a little girl reads aloud from Ludwig Wittgenstein's Remarks on Color, is she heroic, comic, or touching? When homeless men stand against a dark wall, like a police lineup allowed freedom of motion, are they under scrutiny or are you? You may find your own answers, but philosophy is all about the questions.

This time the text belongs to Hill and the speaker remains unseen and unknown. This time, too, the eye and body up against the wall belong to you. It may not seem so at first, in five clean white reliefs at eye level just past the gallery entrance. They may not quite line up with your eye level, but a small box that can serve as a platform invites you to make them yours, as Self. They take the shape of a circle, a square, a triangle, a column, and a cross, for the logic of Minimalism, scientific instruments, or a crucifixion, and each at its center has a lens or two. Peek right in.

Some hold views that change regularly with a click, like slide shows, while others tempt you to move your eye to take in a larger picture. All present little more than a blank surface, but that blank is you. It could be the front of your brow, the back of your head, or a close-up of hair or skin. Every loose strand or tight pore takes on a cool precision. They are like surveillance cameras that turn the surveilling into the surveilled. If they seem more curious than chilling, that perplexity applies in spades to a larger work at back.

There precision has gone out the window, and the first-person narrative is more puzzling still. Two adjacent channels display the same scene from only slightly different perspectives and with a narrow focus that leaves mostly a blur. It appears to show more blank surfaces and more equipment, but who knows just what. It also lies at the end of a carpeted black platform, like a bed for still another vulnerable body. The platform holds seventeen speakers of various sizes and in no particular order, for a voice that seems to move in and out of the video. A man and not a girl is talking this time, in his own voice.

Who is the self here, and is it still philosophy? It has all the right vocabulary for Postmodernism, of frames and their unraveling—and of words as pictures, much as back in the day of text art and "line as language." Their references to an "unforgiving light," "polyrhythmic flickering," and "bursts of physicality" could apply to the smaller work as well, but the dull voice sounds more out of Samuel Beckett or film noir than Wittgenstein. It refers to a "she" once, but from someone no longer "capable of living language without dread." It finds things "perfectly placed as if by a giant hand"—like Bob Dylan "stuck inside of Mobile with the Memphis blues again," seeing Grand Street as nothing more than a chaos of bricks that fell "so perfectly" and "so well timed." Like much in Hill's 1995 retrospective and later at SF MOMA, it allows the visceral alongside the disembodied and the erudite, and it is nice to have his puzzles back.

Peter Campus ran at the Bronx Museum through July 22, 2019, at Cristin Tierney through April 20, and in Times Square through March 31. Gary Hill ran at Bitforms through June 30. Related reviews look at Gary Hill in retrospective, in Chelsea, and at SF MOMA.