Between the Acts

John Haberin New York City

Tom Wesselmann: Beyond the Nude

Philip Guston: Beyond Abstraction

How do you get from figuration to abstraction? For much of the twentieth century, it became a two-sided puzzle.

What could make abstraction relevant for viewers? What could make it relevant for artists trained on experiments in seeing and structuring reality, from Impression to Cubism, Expressionism, beyond? Yet it became as urgent as a new American art. It seemed the very fulfillment of modern art at that—and as much an American vernacular as a comic strip.  In other words, it got real. And then things turned around.

In other words, it got real. And then things turned around.

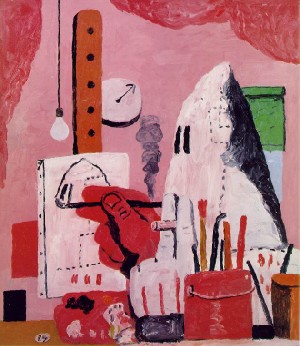

Both Tom Wesselmann and Philip Guston turned it around. Pop Art had come to the fore, but these artists saw something else again. They focused on human figures, including the Great American Nude, the anxious artist, and the still life to accompany both. They produced something larger and smaller than either pop culture or life, and who was to say which? Now two shows hope to catch them in the act, and it turns out to involve the figure as an extension of palpable brushwork. For Wesselman the nude is one promise among others, while for Guston abstraction has first to take on physical dimensions earlier lacking in his art.

A greater America

After Tom Wesselmann, would anyone dare call a painting Great American Nude? It took daring even for him. His nudes, flush with color and ever so close to the picture plane, did much to define Pop Art as an art of sheer pleasure. They pick up on one side of Abstract Expressionism, as an art of pure sensation, while leaving the baggage of Modernism behind seemingly once and for all. They have the feel of a magazine spread, with all its promise of accessibility and unlimited consumption. And then they fight back.

It would take irony, too—because anything less would be awfully sexist. His generation could still dream of writing the great American novel, like John Updike or Philip Roth, both less than two years younger and both, not coincidentally, men with an attitude problem. Beginning a career alongside the space race, he could also dream of a greater America. Now a gallery surveys that career, from one of Wesselmann's first nudes 1961, at age thirty, to his death in 2004. It wants you to know two things: those nudes were not just a phase, and there was much more to him as well.

He looks more consistently experimental than one remembers and, arguably, less sexist. That early nude (actually, to judge by its title, number nineteen) faces calmly forward, her breasts half hidden by her arms rather than on display for men, while clashing reds stain everything around her. She also lies beneath the usual portrait of George Washington, by Gilbert Stuart, putting both men to shame. The show's very last painting, Sunset Nude, marks Wesselmann's personal sunset. The woman looks cheerful enough, beneath palm trees and bright orange clouds, but contained within another outline in flesh tones, as if shrunk to her white flesh and pink private parts. Her blank face echoes, too, in a second woman on TV, as if imprisoned in the box.

Wesselmann called other series his still lifes, landscapes, and bedroom paintings, but they share both a greater chill and a greater physical presence. One collage is an ode to bad taste, including tacky wallpaper, generic spaghetti, and kosher wine. A third dimension enters with shaped canvas and molded plastic, like billboards, much as Roy Lichtenstein leans on magazines for his Ben-Day dots. Their "products" include a full-length automobile, a radio, an apple, and a woman's leg. A construction in cut metal packs a working clock and fan—to the extent that art can work at all. Another nude dissolves into an open mouth and a cloud of cigarette smoke.

Was Pop Art a celebration of popular culture or a critique? Mostly neither, for all its role as stage villain to critics like Robert Hughes and Dave Hickey. It anticipates neither the heavy irony of the "Pictures generation" nor the macho celebrity of Jeff Koons. The movement embraced a wider culture, but as a culture of signs. Much of it is about the making of art and its unraveling, like Lichtenstein's Brushstrokes. It was also equally at home with desire and death—like Andy Warhol with his electric chair, Robert Rauschenberg with his stained bed and CAUTION sign, Jasper Johns with his diver after Hart Crane, Lichtenstein with his drowning girl, or Claes Oldenburg with Manhattan as a slab of raw meat.

Wesselmann, by comparison, never gets beyond the pleasure principle. An automobile for James Rosenquist comes closer to the viewer than his ever could, like a temptation or a car crash. That may be why the show's best surprise is a large abstraction, with all the colors and cut planes of his art, their sensuality implicit. When Marcia Hafif called her color in the 1960s, just up the street, her "Pop Minimal," she was onto much the same. Wesselmann wallows in the familiar, along with the rest of us, its flaws intact. He could still take pleasure in a greater America.

Familiar as old shoes

Philip Guston infuriated almost everyone by abandoning abstraction in the late 1960s, and he would not have had it any other way. He had angered his teachers with cartoons for the school paper—enough to get a classmate, Jackson Pollock, expelled. He had quit figuration in time for Abstract Expressionism, befuddling some of the same tired critics who jumped all over his seeming return to cartooning, only this time on big, bold canvases in oil. And he was helping others to look ahead each step of the way, even if they discovered him more as a fellow traveler than an influence. A decade after he first painted Klansmen and old shoes, political art and appropriation were everywhere. Now more than a quarter century after his death, in 1980, galleries cannot get enough echoes of street art after Jean-Michel Basquiat and graphic novels.

Guston is still infuriating, even as he has become painting's secular Jewish saint. He is also still the latest fashion. Just when abstraction is back, big time, so is he, with ten years of it. A new show promises to reclaim him for the genre, to answer a mystery, and to fill a gap in his career. What was he doing from 1957 to 1967, and could it connect abstraction to figuration after all? Could it alter his reputation as an abstract artist?

Part of the mystery was always the nature of his first paintings in New York. At once colorful and glistening, but also misty and subdued, they earned him the label Abstract Impressionist, and it was not exactly a compliment. It has left him a lesser figure in a great movement. And of course part of the mystery, too, is how he hit upon not just a new subject matter, but a new style to go with it. If critics were impatient with the mist, so it turns out was he. And if his late style was up-front and deliberately clumsy, with figures isolated in black and white against acid pinks and muddled grounds, so, too, were his last abstractions.

Part of the mystery was always the nature of his first paintings in New York. At once colorful and glistening, but also misty and subdued, they earned him the label Abstract Impressionist, and it was not exactly a compliment. It has left him a lesser figure in a great movement. And of course part of the mystery, too, is how he hit upon not just a new subject matter, but a new style to go with it. If critics were impatient with the mist, so it turns out was he. And if his late style was up-front and deliberately clumsy, with figures isolated in black and white against acid pinks and muddled grounds, so, too, were his last abstractions.

In truth, those years were visible enough in the Philip Guston retrospective, in 2004 at the Met, only hard to pick out from his larger history. It was also hard to see them as a gradual evolution. If Guston was so polarizing, how could his work be anything but polar opposites? Yet by 1967 a tangle of black brushstrokes had gathered near the center of canvas after canvas, in a shape much like a torn and tortured brain. And by then his palette had shrunk almost entirely to pink, black, and gray as well. In the show's last painting, the black tangle nestles into a looser tangle of gray and gray alone, as if in need of a long rest.

By 1957 he has already blown away the mist, as part of a love-hate relation with formalism itself. Paintings approach a fixed palette of basic colors, including red, yellow, blue, black, and green—but with two shades of blue and plenty of pink and gray. The colors also congeal into overlapping patches, approaching a formal architecture, but with no particular logic and no sign of a grid. In the next few years the patches multiply further, with purple emerging from the overlay of red and gray. They also retreat from the edges of the canvas, leaving nothing but white, while works on paper resemble cels in an abstract comic strip of indecipherable signs. All-over painting, be gone. And then the patches grow again, only with fewer colors, the denser tangle, and the growing separation of figure and ground.

He had his notorious show that followed in 1970, in his late fifties, and it announced the isolation of not just a figurative painter, but also of age. He could associate the Klan with assaults on Jews from childhood, but the air of confessional painting belongs to an older man in his studio, not least because confession came with the less than frank irony of a cartoon. Could those missing ten years show him at last as a mature artist in the prime of life? Probably not, but they do recover him for his time. They might not earn undiluted praise did he not already have a fan club eager to embrace them, but one can see the white borders and think of Joan Mitchell, see the blacks and think of late Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, or Deborah Remington or see the tangle and ambivalence and think of Willem de Kooning at different stages of his career. Mostly, though, they are a reminder that nothing in art comes out of nowhere, not even the blackness and the tangle.

Tom Wesselmann ran at Mitchell-Innes & Nash through May 28, 2016, Marcia Hafif at Fergus McCaffrey through June 25, and Philip Guston at Hauser & Wirth through July 29. Related reviews look at Guston's retrospective at the Met in 2004 and Guston's self-doubt.