Pop Art on a Budget

John Haberin New York City

Claes Oldenburg

Tired of blockbusters that skew museum priorities? Tired of big names and big money? Claes Oldenburg lets art down, and I love it.

Try and try again

His soft sculpture must have looked like a throw-away from day one, and it does literally let you down, but is it really? It was just one stage in a memorable career. The Whitney returns to when Pop Art looked a lot less slick and happenings were happening. Which was closer to sheer chaos, Oldenburg's sculpture and installations or the city York itself?  And then the Museum of Modern Art offers another side of the artist, with claims on art history. Together, they supply a 2009 retrospective.

And then the Museum of Modern Art offers another side of the artist, with claims on art history. Together, they supply a 2009 retrospective.

What if a museum just went about its business—of sticking up for the art it knows best? When it comes to Oldenburg, museums had better know their limits. The Whitney summarizes his early years with work from the museum's collection. Then comes a leap ahead to the 1990s, for a single collaboration with his late wife, Coosje van Bruggen. The exhibition, picking up at MoMA, draws on fifteen years of loans from the artist as well. The film gallery tackles the fabled happenings of the early 1960s.

Nearly four years later, I had his Mouse Museum to myself. I had read the obituary of Annette Funicello, the star and guiding spirit of the Mickey Mouse Club, barely an hour before—pure coincidence, but also a sign of the enormous reach of Claes Oldenburg. He conceived a "museum of popular art, n.y.c." in a new studio in 1965, the very year of Beach Blanket Bingo. Oldenburg chose nearly four hundred relics from his loft on Fourteenth Street, on his usual themes then of toys and food. It took just seven more years and Documenta, the arts festival in Germany, to morph into mouse ears. This artist could not leave anything out.

As a postscript, his work comes in three stages, but its evolution is not easy to pin down. More than fifteen years later, the Whitney gives it another shot. Nineteen drawings from the collection return to four crucial years, starting in 1959—by coincidence, one year after the Mickey Mouse Club aired its last on TV. Three titles from those years say it all. Oldenburg began out on The Street, set up shop at The Store, and finally found himself in The Home. The drawings try out ideas for later work as well.

Oldenburg, who died in 2022, got started with those early installations in performance—real stores but with merchandise that might have come from anywhere, in the garbage or on the cheap. Artists in the early 1960s were living on the cheap, too. Soft sculpture, like a sagging toilet, adds a second body of work. It, too, starts with whatever it takes to get by, but after late Modernism had given new meaning to the weight of material objects. Last comes the work for which he is known best today, not sagging, but punning on history, like lipstick in the guise of a classical column. Oldenburg had entered the museum, just in time for his art to begin there, too.

Do the divisions in his work, then, suggest periods in his life? You might think so, and these drawings hang on the floor otherwise reserved for the Whitney's collection, master works everywhere. Still, Oldenburg's dense scrawls are not the obvious stuff of museum pieces. Nor is his mainstay, puns. A monument or a cathedral can take the form of a teddy bear or a fire hydrant, literally larger than life. And his three phases could be three ways of locating the public in public sculpture.

A soft spot for pop

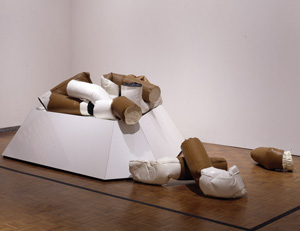

Back at his retrospective, everything attests to Oldenburg's modesty, far from the darker and more glittery soft sculpture of Yayoi Kusama. The opening room holds his signature ketchup and fries, a BLT with olive and toothpick, a blender, and a toilet. Pop Art often descended like lightening—for Roy Lichtenstein the figurative pow and zap of a comic strip, for Andy Warhol the "sinister Pop" of Orange Disaster and an electric chair. Oldenburg descends to everyday guilty pleasures, and he descends less than gracefully. The stuffed-canvas ketchup sprawls out over the fries like a couch potato. One can feel a cold, hard toilet seat melting out from under one.

The next room scales up the action to more comic proportions. A motorized ice bag pulses slowly up and down, like a thinking cap for giant soreheads. It alone displays the artist's talent for scale. Sketches lining the walls show these works coming to be, plus some comic architecture that never did. No, a fireplug never did morph into a Chicago skyscraper. As for Oldenburg's giant Typewriter Eraser and Crusoe Umbrella to the even more stately Clothespin, the Whitney stops just in time to miss them all.

The back room has memories of The Store at 107 East 2nd Street, where Oldenburg sold sculpture made of canvas, burlap, and muslin dipped in plaster. Compared to the neatness and bustle of related display cases in MoMA's collection, the room and its posters look spare to the point of self-effacing. How gritty it must have seemed, as if Oldenburg had dipped real clothing in blood. This store lay not all that far off the Bowery, and it looks it. A fancy clothing store has since replaced CBGB, and the daughter of Brice Marden has closed her trendy Lower East Side gallery. Warhol's Factory off Union Square might have had a soft spot for the neighborhood's newfound glamour.

The half-improvised happenings would not. With Oldenburg's help, the Whitney has rounded up seven of them, and they play simultaneously on four walls. One runs two hours, but most are a few minutes at most. You could see them all in a single visit. Artists and other friends drift way and none. They climb out of bed, down from the rafters, up a long road, and down a university corridor, maybe in search of a really good party.

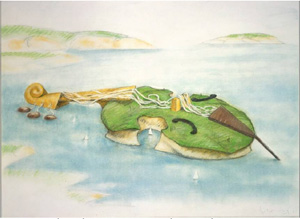

Finally comes The Music Room, an extended tribute to the summer of love—and I do not mean Robert Indiana. Its inspiration came from van Bruggen, the writer and curator whom he married in 1977. She had a fondness for Jan Vermeer, especially Vermeer's women. Over the course of a decade, the idea spawned a soft viola, the gently curving tower of Leaning Clarinet, and a ludicrously entangled French horn. It also spawned still more sketches for still more plans. He must have dreamed of departing with his wife for his Soft Viola Island.

Even before the Great Recession, the Whitney had been planning a quiet spring. Two theme shows made a particularly low-budget start. "Synthetic" and "Sites" both again took work from the permanent collection, and both felt like missed opportunities. Instead of a bringing fresh eye to familiar art, the two left things strangely empty, as if work that did not fit the theme had to go. One could imagine them as the core of two shows—histories of house paint and raw earth. Each in turn shaped Abstract Expressionism, color-field painting, and Minimalism, land art, and the mess of art today.

Soft ambitions

The Whitney's version of Oldenburg has ambitions. It is out to capture a critical moment in art, of the happenings and those who made them happen. It outlines a retrospective all the same. One can only admire a museum that can pull this off from mostly its own holdings. It is also Oldenburg's tribute to a marriage. While van Bruggen makes only a late appearance, they share the banner outside the Whitney.

Yet it leaves out something crucial, Oldenburg's modesty. It moves seamlessly from the Bowery to the Baroque, from French fries to a tropical paradise. It assimilates too easily the mad rituals of the happenings, the ugly indulgence of giant Fag Ends, and the caked and battered clothing from The Store. It conforms a little too easily to the artist's complacency and perpetual whimsy. I cannot blame his wife for everything. Oldenburg has more than enough good cheer to go around.

Yet it leaves out something crucial, Oldenburg's modesty. It moves seamlessly from the Bowery to the Baroque, from French fries to a tropical paradise. It assimilates too easily the mad rituals of the happenings, the ugly indulgence of giant Fag Ends, and the caked and battered clothing from The Store. It conforms a little too easily to the artist's complacency and perpetual whimsy. I cannot blame his wife for everything. Oldenburg has more than enough good cheer to go around.

At his best, he transforms one's perceptions of both art and ordinary life. His giant Clothespin in Philadelphia again pays tribute to his love for things that art often overlooks. Yet it also shows his formal understanding of public sculpture. The splayed base of the Clothespin echoes the spread feet of a striding warrior. He is parodying heroism, but he is also elevating less heroic moments in life.

The same strategy infects all his public commissions, and it makes them much of his best work. Typewriter Eraser has the tilt and bristles of a mammoth bird in flight. The umbrella has the rusted wheel of a colossal charioteer. A Batcolumn and Lipstick (Ascending), neither among the Whitney's sketches, play with noble columns as richly as Barnett Newman in his Broken Obelisk. When that ambition peeks out, as with the clarinet, it animates his late work as well. The sketch of a bent screw never did become a railroad crossing, but it should change how one sees the freight bridges into New York City.

His early work has a public side, too, from The Store to the collective happenings. He plays at once collaborator and shaman. He comes in person to the happenings, with his glasses, his intent stare, and the black suit of a magician. Perhaps only a shaman could assemble such loose proceedings. Dorothea Rockburne and Lucas Samaras pass through without making art, Carolee Schneemann without feminism and performance, and Henry Geldzahler, the arts administrator, without buying it all up for the Met.

Oldenburg with his soft toilet may remain an aside in Pop Art. He shares lipstick with James Rosenquist, but without the painter's nostalgia and spectral detachment. He never depicts pop culture at second hand, like Lichtenstein or Warhol. He had too much equanimity for their darkness or glee, not to mention too much love of the thing itself. His sculpture is way too tactile—and way too immersed in ketchup stains and toilet training. Maybe the greatest idealists always catch one with one's pants down.

Look, Mickey

MoMA, too, shows Oldenburg piecing together a career, starting in January of 1960, when he shared the basement of Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square with Jim Dine. With The Street, the thirty-year-old Chicago native (born in Sweden) cobbled together a panorama of his New York, in cardboard, newspapers, and rags. A year later he opened The Store, long before the waves of Lower East Side and East Village art. Who could have imagined the need for an Affordable Art Fair back when everything was for sale, starting at $21.79, and everything was out of a larger world of impulse buys, like lingerie and Seven-Up? Some of the sculpture even represents price tags, as low as 39¢. Look at the bright colors and the rags soaked in plaster, and try to remember the roughness of early Lichtenstein as well—like his breakthrough painting from that very year, as it happens, Look Mickey.

Some sculptors make public art, like Alexander Calder, whose planes Oldenburg pirated in 1971 for (yes) mouse ears. MoMA has had a white version in its sculpture garden. And some made Pop Art, like Warhol, whose influence just will not go away. Oldenburg sought a genuinely popular art, and one can ask how that differs and whether he succeeds. The early work looks a bit out of place en masse on the museum's white walls, but also funky and alive. It stops just short of his own breakthrough to public art, although it includes his first inflatable sculptures, a cheeseburger and an ice cream cone. The museum atrium has the slicker display cases of Mouse Museum and its 1977 addition, a Ray Gun Wing.

Maybe a true retrospective will always be out of reach. Oldenburg's best work depends too much on its place and scale. It also depends on those close encounters with art of the past, its columns and statues, as both parody and tribute. MoMA does include several flags and a Soft Calendar from a single month in 1962. You can see Jasper Johns in their patterns and numbers, but that is up to you. But then that cheeseburger does come "with everything."

You can also see the punster. A rifle looks suspiciously like a schnozzola and the very first "Empire" ("Papa") Ray Gun suspiciously like a male's balls. The impulse truly takes off in Ray Gun Wing, named not for its shape but its discovery—of gun shapes in everything from hardware to a straw. Mostly, though, one sees a young artist caught up in his enthusiasm, not least for the coarse, unappetizing fabric of his favorite things. Pretty much the entirety of The Store consists of clothing and food. His greater scale, comfort, and sentiment after the 1980 seems blissfully far away.

Oldenburg's cardboard preserves the look of the handmade, and the sewn vinyl of inflatable sculpture reflects the skills of his first wife, Patty Mucha. He is not, though, above appropriating toys outright, and he is not above promoting himself. He genuinely cared about the popular in Pop Art, even if not many would have ventured to a "store" somewhere east of the Bowery for art. For the curator, Ann Temkin, images of a cemetery reflect summers in Provincetown and fears for the "commercialization of history." No doubt, but his first work includes its own flyers and posters, hand lettered about as badly as he could. These days, Martha Rosler has to try a lot harder with her own yard sale in MoMA's atrium, and she also has to sacrifice the fun.

Call the work a celebration or a satire, appetizing or disgusting, deeply personal or studiously neutral, or just plain funny. Desserts have neither the chill of Wayne Thiebaud nor the lushness of Thiebaud drawings. Much of the food lies greasy and limp. The very collapse of collapsible sculpture is a refusal to make great art. I still wanted a mature Oldenburg's ambitions—and I wanted, too, a time when one could buy all this at bargain prices. I shall just have to settle for the mouse ears and the memories that I could never have had myself.

Claes Oldenburg ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through September 6, 2009, "Synthetic" through April 19, 2013, and "Sites" through May 3. Oldenburg returned to The Museum of Modern Art through August 5, 2013. The drawings came to the Whitney on extended exhibition in July 2026.