The Bauhaus in New York

John Haberin New York City

Go beyond the blog. Search or browse this site's hundreds of longer essays in review.

Anni Albers and Josef Albers at MetLife

A decade before World War II, Anni Albers imbued tapestry with the scale and visual intensity of postwar American art. So why have you so rarely seen her work?

An upscale Chelsea gallery makes the case for Albers as an independent artist and more than a painter in disguise. She took her teaching and collaborations seriously, and she thought aloud in thread. Oh, and what about her husband, remember him?  With a mural once left for lost, Josef Albers brings the Bauhaus to New York, big time. Now, at last, neither Albers is a footnote to abstraction or to the other. The artists and the city alike deserve these acts of recovery.

With a mural once left for lost, Josef Albers brings the Bauhaus to New York, big time. Now, at last, neither Albers is a footnote to abstraction or to the other. The artists and the city alike deserve these acts of recovery.

A puzzle or a painter?

You may know Anni Albers as head of the weaving workshop at the Bauhaus—or as the wife and companion of Josef Albers, the painter with a lifelong pursuit of the properties of color and a square. Either would make her one of the most extraordinary figures in early and late Modernism. She alone as a women had a leadership position at surely the most influential design school in history. Long after Hitler shut the doors on "degenerate art," it stood for rigorous design as essential to art and art as essential to everyday life. After she and her husband came to America, they taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, and they explored together the potential of hard-edged abstraction. She had the first exhibition of textiles ever at MoMA in 1949, before it toured the country.

Either, too, could relegate her to a footnote to history much like Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and they have. No other Bauhaus workshop fully accepted women, and no one wants to go down in history as an artist's wife. (Just ask Lee Krasner with regard to Jackson Pollock.) Only last year, the Guggenheim followed the couple to Mexico in search of monuments to Pre-Colombian art, and guess whose works on paper it included. Accounts of Black Mountain as a laboratory for experimental art are likely to mention Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, John Chamberlain, and Dorothea Rockburne, but not her. That show at MoMA must have seemed a long time ago at her death in 1994, at age ninety-four.

The show does its best to rescue a woman for the canon and tapestry for art, but it presents her more often as something of a puzzle and a painter. It can hardly help either one, with a predominance of works on paper rather than weaving, but the puzzles begin in the first of four rooms. A long, narrow tapestry rests on a raised platform at its very center, like the path to a throne. This is not everyday home design, and its coarse texture could almost be unraveling, as indeed with Samuel Levi Jones today. So do successive dull gray weaves, where paler and thicker threads do not just hold the pattern together, but also draw one another side to leave gaps, as if they had never quite come together in the first place. If Albers could not be bothered to finish the job as a fabric maker, was she a painter in disguise all along?

One might think so from her beginnings as a painter and the discouragement she received before switching media, even at the Bauhaus. One might think so, too, from the show's climax, a ten-foot wall hanging in deep, bright red—a 1968 commission for the Hotel Camino Real in Mexico City. Small triangles in varying shades of red ripple through it all, playing against the grid. Red weaves through lighter and earlier threads beneath, from 1946, as well as through slim black verticals here and there, carrying them into the third dimension. Once again, this is not everyday quilting, any more than her black and white triangles on paper. Simple patterns take on unexpected activity, just as for Sol LeWitt and Minimalism, Bridget Riley and Op Art, or Diedrick Brackens in African American tapestry today.

They have an obvious parallel in Josef Albers, who uses shades of a single color for his many versions of Homage to the Square. He, too, makes a point of rigor in two dimensions, even as the nested but not concentric squares all but tumble forward off canvas or paper. She could be challenging him as well, with a less dryness and greater subjectivity. She also, it turns out, introduced him to Mexican civilizations rather than the other way around, as with that carpeting to an ancient throne. She is also still a weaver. For all the talk of Modernism as formalism or the triumph of painting, the Bauhaus dared all along to take art as a tool to transform life, and Anni Albers held it to account.

She had an early introduction to design from her father, a furniture maker, although also a commercial success against which to rebel. She met her husband in attending his design class, in glass. Look again, and the layered threads pulling each other apart call attention to weaving as painting and as weaving in cotton, linen, or wool—much as later artists like Frank Stella demanded to treat paint on canvas as about painting itself. The appearance of Op Art comes from treating color as a kind of weaving, too, even on paper. Like her husband and his works in series, she was not one for disguises after all, give or take fabric as always about dressing up. It will take a fuller retrospective to show where the disguises left off.

Restitution and recreation

The return of Josef Albers to the MetLife building is not just a restoration, but a reunion. It gives his mural its place, in a landmark designed by Walter Gropius—on the hundredth anniversary of the Bauhaus, which meant so much to both. Albers met his wife there, in his design class, and he had been a student there before her. Anni Albers rose to direct a department herself, the first and only woman to do so. Gropius had created the Bauhaus in 1919, when he merged the Grand Ducal School of Arts and Crafts and the Weimar Academy of Fine Art. He also designed its second home, in Dessau, before the Nazis chased it to Berlin and, ultimately, to its death.

The return is an act of restitution as well. When Met Life took over the former Pan Am building in 2000, it took down the Josef Albers mural simply because it did not care for it. It then felt obliged to destroy it because of the asbestos behind it—or so the company says and The Times duly repeats. (See a parallel here with articles regurgitating Donald J. Trump's proclamations of exoneration and attacks on Joe Biden or Hillary Clinton? Hey, it is only reporting actual allegations and maintaining "balance," and it can then devote a follow-up to fact checking. What not to like?)

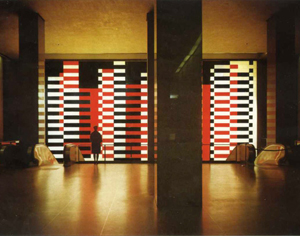

If the mural is thus not a return after all, but a recreation, that accords with the Bauhaus, too. It believed in design as functional and reproducible, for the people. (So much for the "originality of the avant-garde.") If a copy in plastic laminate sounds a little tacky, the artist made the original in Formica, and it has all the greater translucency under lobby lights. Albers, who has appeared in a show of "Seeing Red," created stacks of horizontal strips in black, white, and red—nearly five hundred in all. They form distinct but interlocking columns, each with its own color set, which then comes apart a row or two from the bottom.

If the mural is thus not a return after all, but a recreation, that accords with the Bauhaus, too. It believed in design as functional and reproducible, for the people. (So much for the "originality of the avant-garde.") If a copy in plastic laminate sounds a little tacky, the artist made the original in Formica, and it has all the greater translucency under lobby lights. Albers, who has appeared in a show of "Seeing Red," created stacks of horizontal strips in black, white, and red—nearly five hundred in all. They form distinct but interlocking columns, each with its own color set, which then comes apart a row or two from the bottom.

The columns carry the eye across the mural's fifty-five feet and into the lobby. Albers never worked on that scale again, and it also brings out the lobby's height. The work hangs over escalators leading up from Grand Central Station. With one's back to the mural, one sees comparable rhythms in the facing pillars and mezzanine. I have no idea how much a lobby renovation looks back to Gropius, but it works. Modernism and New York City alike presents grids in motion, and Piet Mondrian in America looked to both. Albers can be dry and dogmatic, but he did call the mural Manhattan.

Not that he and Gropius could recreate the Bauhaus in exile, but then the Beatles never had a reunion either. Each had moved on, and neither artist was above criticism, no more than John and Paul. At the completion of the Pan Am building in 1963, Modernism seemed a settled matter, but also part of the past. It could seem oppressive as well, even apart from issues of gender and diversity. Critics slammed the building for cutting off views from Park Avenue of the New York Central building (now the Helmsley building) and Grand Central in favor of a glass tower—much like criticism of Hudson Yards in relation to the city today. When a crash put an end to the roof's use as a heliport, the disaster felt like a metaphor for urban development.

Still, the Bauhaus had its populist side all along. Did it sell out to corporate interests in midtown Manhattan, or did it aspire to a gathering place for residents, workers, and commuters? Maybe both, and I often take refuge from New York's winter cold and summer heat by taking those escalators on my way north. The space feels less open now, but also less chilly and confining. It contrasts with another cheap replacement from those years—Penn Station, with its low ceilings, ugly materials, and lack of anywhere to breathe or to rest. Blame Robert Moses as "master builder," a sports arena, Pennsylvania Railroad, or real-estate developers, but do not blame Modernism.

Anni Albers ran at David Zwirner through October 22, 2019. Josef Albers returned to the MetLife building in late September.