All Over the Map

John Haberin New York City

Gallery-Going: London in Fall 2003

How did five years in postmodern art get to seem so long? I had not seen London in five years, but even a first-time visitor would perceive change, literally, in the air.

One can see it in the cranes towering over the South Bank, already helping to sweep the Docklands studios and distant galleries into the fabric of urban life. One can see it in the light reflecting off the dome of City Hall and Millennium Bridge, as if leading the way to Tate Modern and the Saatchi Collection. One can see it in "the Gherkin," Norman Foster's Swiss Re tower of green glass, like a warhead set to launch over Whitechapel High Street and perhaps East London's oldest gallery. One can see it in the real-estate signs boasting of sales all over the East End.

What is it about British art, and is it really all that different? New Yorkers know well that extravagant, frightening mix of art, real estate, and high finance. Do they know it all, though—and do they see it in light of the same modernist traditions?

Let me offer a taste of one critic week in a big city not his own. It goes with my postcard of the number 8 bus, running all the way from East London to New Bond Street, past the sedate confines of Cork Street galleries.

Art as urban adventure

London does make the American scene seem like business as usual. The loss of the World Trade Center only magnifies Modernism's lasting imprint on the Manhattan skyline, and the future is up for grabs. New York's Chelsea has grown denser than a mall, but the names on gallery windows still look familiar from Soho and 57th Street. Co-ops have made it to Dumbo and Williamsburg, but few galleries there have had staying power. Soho itself stands as a warning of the danger of success. No wonder it took the Britpack, at the Brooklyn Museum a few years back, to get politicians or the press worked up about art.

London's scattered energy could resemble Williamsburg blown up to the size of a city. How did my friend find these places? She had visited before, of course. Even she, however, made a few wrong turns, and she, too, marveled at spaces that had changed their whole design since her last visit. This city revels in change. New Yorkers approach aging warehouses like squatters, barreling right in and adding sheetrock. London's additions to factory spaces make a gallery visit an architectural tour as well.

I found especially striking the studio collectives, sometimes with a gallery, where New York would leave artists fending for space and forking over the rent. On Chisenhale Road, in a rapidly gentrifying sector off Victoria Park, Faisal Abdu Allah was rigging a multimedia garden of Eden next store to the broken windows of a deserted brewery. Like Pip in Great Expectations, I half imagined Miss Havisham swinging from the rafters. Then again, Approach Gallery nearby slips in over a pub. Thankfully, one studio building houses a gallery called, more austerely, The Nunnery.

Miles away by the Thames, a former firehouse holds several spiffy floors of residential studios. Two men were at work on videos, one seemingly trapped in the monitor itself. Below an artist was compiling tabloid headlines, as an encyclopedia of hysteria since 9/11.

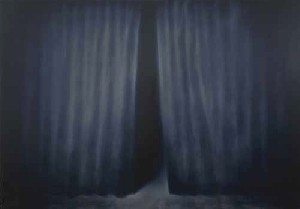

Those sticking to commercial dealers have even more of an adventure. Flowers, with branches in Cork Street and Los Angeles, was using its grittier Hackney location for Ken Currie's subdued realism. The blurry, isolated humans, in soft white and blue against velvety black, can feel like a cheat, both technically and in their aura of suffering. Some even have paper bags over their heads, like children playing at Colombian terrorists. Yet I admired the texture and frontal poses. On the next wall, paintings of translucent curtains, parallel to the picture plane, carry his figurative logic to where, perhaps, it truly belongs.

From there one has a short walk to the elegance of Hoxton Square. At White Cube, well-dressed young men and women were supervising the record opening-day attendance for Damien Hirst. I recognized the butterflies pinned against sky-blue backgrounds, the embalmed zoo, and the glass-enclosed shelves that assimilate museum displays to scientific experiments. This year, however, the experiments are getting messier, the beakers and vials dripping with blood. Hirst takes seriously the associations of fine art with a kind of living death, an act of preservation that nonetheless highlights mortality. Can I take it as seriously, however, after some two generations of appropriated appropriations and Hirst's rounds of pop stardom?

Taking art lying down

My friend definitely could not, at least not after Mark Farrington's rather more cluttered butterfly collections at Mobile Home, with a plodding insistence on outsider art. So off we walked further west, to the relative isolation of Victoria Miro, without a party venue in sight. by Two videos Isaac Julien describe a coming of age, derived from the narratives of Derek Walcott. Set in Baltimore and an unnamed city, in the present and at a birthday party perhaps forty years ago, they ask one to look closely at people. They ask one for patience with a young man caught between innocence and intoxication. They ask one to recognize black people caught between urban America and the intimate connections of a Trinidad community.

A bus ride later and a walk beside the Thames took us past Tower Bridge. At Wapping Projects we entered a fortress-like interior broken by sunlight and shadow, not to mention by a cafe. The old factory and curating work so well that I did not even realize that I had seen a group show. Folding chairs divide the central room, in single file facing an opening in the brick wall. I thought of a classroom with brutal discipline in training for a vision. There and in surrounding rooms, photographs ring more changes on "The Chairs"—from discarded piles of them to sites of solitary torture.

If chairs make one think of therapy or of rest and relaxation, one can head to yet another East London stop. At Whitechapel, still among the fanciest galleries, Franz West sets out plenty of chairs, beds, and other props, all waiting to be touched. I honestly could not see the Austrian artist's alleged Freudian associations. Worse, the numerous exhibition posters amount to filler. However, by then I definitely appreciated the chance to lie down. Pleasant dreams.

Not that traditional London looks compact either. Contemporary art sits off in the middle of Kensington Gardens, at Serpentine. And at Lisson, about half a mile north of Marble Arch off Edgeware Road, Christian Jankowski had surely the best commentary on the art scene yet.

Jankowski turns people into sheep, like Hirst's but perhaps a bit more alive, and he means one to see through this magic act. A second video offers art as one huge preadolescent fantasy. Kids read actual interviews with name artists, as best they can, off cue cards. They have the dress and the mannerisms down pat. They may stumble here and there, but the words never did make that much sense. At the end, the charming young hostess brings them all together for a splendid gallery opening, with a faux champagne taste.

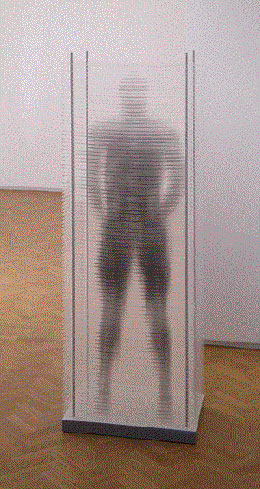

Even Cork Street, behind the Royal Academy, still has some fun left. At Alan Christea, Julian Opie tries much too hard to turn painting into fish wallpaper, but I enjoyed the catalog pretending to be an evening tabloid. Marilene Oliver at Beaux Arts does better. She inks black metallic circles on stacked acrylic, and the illusion took my breath away. The ghostly standing presences evoke the sensuality of nude sculpture, and the echo of medical imagery makes her glass a window on mortality. Hirst could only envy this.

Plus ça change

I saw a group show on the South Bank, obviously much changed since Tate Modern, with architecture by Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron. I caught the Bridget Riley retrospective at Tate Britain. I even had time for the great Courtauld Collection, of art from Robert Campin through Edouard Manet, with his Bar at the Folies-Bergère, and Jan van Eyck, with his equally dazzling mirror, or the Leonardo cartoon at the National Gallery. I must have worn you out, however. Let me rest, then, on the whole mix of old and new, of commercial galleries and public spaces, all in a city in transition. In London, it seems, art, finance, and public investment all get along just fine, thank you. That very fact, however, should get one questioning the entire story of rapid change thus far.

Sure, Tate Modern deserves the crowds, not to mention the members sharing wine and hors d'oeuvres on a balcony overlooking the Thames. Still, a middling collection of modern art has merely crossed a river. Somehow it makes sense that Hirst was back at White Cube, as if he had never left. It makes even more sense that White Cube got its crowd estimates in the papers the next morning. A disconnect remains between the inside track of Young British Artists and their own popularity. An even larger disconnect remains between them and great the diversity of approaches in artist studios around town.

If one can easily exaggerate change, one can also forget how much London and America still depend on one another. Last fall London picked up retrospectives of Eva Hesse and Barnett Newman. This fall I passed up the chance for another look at Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, a German Expressionist whose retrospective I had seen in Washington, and a big video collection formerly at P.S. 1. Instead, I caught the work of John Currin, a star of the 2002 Whitney Biennial, on its way to New York. I was relieved to find that my British friend could make even less sense of it than I.

Inside Tate Modern, nothing gets as worshipful a display as Robert Smithson's film of Spiral Jetty, Mark Rothko's murals meant for New York's Seagram Building, or a Bill Viola's five-screen, slow-motion spectacle of fire and of water. Outside, Paul McCarthy, born in Salt Lake City and even featured in the 2004 Whitney Biennial, has mildly risqué cartoon sculpture, huge balloons daring someone to bounce off them or toss a dart. In turn, New York this last year hosted prominent shows for Tracey Emins, Rachel Whiteread, Sam Taylor-Woods, and Bob and Roberta Smith. Now this same fall one has the dense abstractions of Julian Lethbridge. Parallel lines of a single color, reminiscent of Jasper Johns, cross broader strokes of bright white, all covering still deeper background tints. They combine a self-conscious catalog of brushwork and painterly scales, a palpable surface, and, at a distance, a sudden burst of color.

Some never do return to England. In 1984, Malcolm Morley won the first Turner Prize without leaving the United States. If the ensuing years seem like an eternity in art and celebrity, another expatriate earned longer headlines in 2003 than even Hirst. David Hockney with his claims for the camera obscura in art history manage to assimilate Jan Vermeer to Los Angeles.

No doubt dealers in both cities attend the same art fairs well beyond the Biennale or the Armory Show, face the same financial pressures, and leap at the same opportunities. New Yorkers who waited for tickets to "Matisse Picasso" this spring will have no trouble imagining the lines in London, where no one had to take the 7 line to Queens. Those who can hardly keep track of U.S. galleries here will have trouble attributing all the buzz in London to art-world stardom. Dealers who can no longer afford Chelsea will surely sympathize with the decentralized London gallery map.

The tastemakers

Obviously I am describing the meeting of art and commerce in another way, as the globalization of culture and finance. Yet again the story has grown too pat. Consider for starters the dearth of American artists in commercial galleries. I spotted only David Salle and Sam Francis—and only because Francis's widow has settled in England. Something does keep the scene in London more insular than in America while also displaying more of a sensational, public face. The paradox, I want to argue, suggests a vital continuity in British art amid all the sensation.

Certainly the usual accounts point to change, big time. Once, they insist, Britain largely disdained modern art in the interests of high culture. Now openings are events in popular culture. Once artists moved between the West End and the academy. Now they make the gossip column and their images contribute to advertising.

Critics put it down to passing trends at best, opportunism at worst. Careerism, one notes, came naturally to students in the Thatcher age. Boosters disagree, arguing that British art simply has grown up. Why did art use to act so dreadfully serious? Who says that art has reaching an audience means selling out? In her lively book The Tastemakers: U.K. Art Now, Rosie Millard of the BBC repeats those questions over and over. Art, she suggests, draws a crowd because people get it, and whatever is wrong with that?

Her very existence appears to confirm a shift in tastes. Her work takes her from the East End to the Oscar ceremonies. Her book constantly drops names, where a traditional critic would stop to describe, interpret, and explain. Even her back-cover photo, with an electric-blue shirt that matches both her watch and her eyes, keeps up with the latest. This woman would definitely stand out at an opening—or on the tube.

The glibness of her argument, too, goes with its conclusion. Logically, she is attacking a straw art, and I do not mean a sculpture by Deborah Butterfield. Modern artists have dreamed of changing the world and despaired of it, but they rarely set out not to find an audience. If anyone set out to be banned, it is more likely to be the Chapman brothers than James Joyce, who lacked the sense to spot its marketing value. By asking why art must be obscure to be good, she begs the question of why it must be popular. Movies, for that matter, have to earn money, but box-office receipts would make a dreary film history.

It does take creativity to break out of old habits and reach others. It takes guts to stake a life and a fortune on a gallery space off the beaten track. Sometimes, it can take ruthlessness as well. Can there be more to the picture, however, than either cynicism or success? Consider just the practical demands of such a dynamic urban landscape.

Who cares?

Postmodernism, I once argued, may be Modernism pressed for time. In London, it may instead be Modernism pressed for space.

With so much on a single Chelsea block, New York artists have their hands full hoping to grab attention and to linger in one's memory. It may reinforce the recycling of familiar images and outlandish gestures.

Once London outgrew Cork Street, it had nowhere as compact to go. A historic city does not easily give over a community. A strong central government does not easily let small business break the rules. When a dying quarter opens up, as along Canary Wharf or the South Bank, large commercial and public development sweeps right in. Artists and dealers alike must learn to keep on the move, as in New York's changing Lower East Side.

They also must entice patrons and the press to make the journey. As in New York, that almost demands outrageous gestures. Unlike in New York, however, it has to put a premium on familiar names but unfamiliar outcomes—in short, on the latest thing. An exhibition at Hoxton Distillery winks at the constraints. "Group Shows," this group show points out, "Are a Waste of Time."

The diversity works, too, because people care. The changes could not take place without public funding for art, architecture, and urban renewal. Artists could not survive like this without a modicum of health care and other public assistance. America must seem like a discouraging, Bizarro universe, and so it is. Even New York's parks evolve in spurts, depending on private, neighborhood donors. When The Onion pretended this March that Congress had approved arts funding by mistake, a friend overseas believed it.

In London, people do care. They care enough to hunt this stuff down. They care enough to expect free entry to museums. They care enough to treat artists as celebrities. It may seem as new and as transient as any gossip column, but it really goes back to a long and curiously stodgy tradition. The British treat art as part of culture—often enough, as part of a specifically British culture.

Putting Modernism on the map

The connection began well before Modernism. In France, the Royal Academy ranked art by technical skill, by adherence to tradition, and by genre. The higher genres corresponded to the gravity of the subject. In Great Britain, as seen in last year's exhibition of "The Victorian Nude," academic art had rather to please and to instruct. With Manet, the French took umbrage his mix of genres and careless perspective. With James McNeill Whistler, the English made a scandal of a strapless evening gown.

On the one hand, London stayed notoriously hostile to Modernism. On the other hand, it demanded more of modern art. Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud do not just make figurative art. They also paint the human condition. Pop Art in America rarely loses its detachment. One never knows just when to trust in its pleasures, when to side with the mass consumption against fine-art tradition. When Richard Hamilton asks, Just What Is It That Makes Today's Homes So Different, So Appealing?, one cannot overlook the loss of a finer past. American culture had invaded, and art still had laughter if not beauty as a defense.

I can see the demand for something extra, something serious, in Riley's retrospective as well. True, she can come close to Sol LeWitt, especially in her preliminary sketches with their penciled notes. One can see them as minimal or conceptual art, a plan waiting for large-scale, painstaking execution. However, the work still has to do something, to act on one's perceptions—and it does, big time. The closer one approaches her compositions, in fact, the more the illusion leaps off the wall, and the less geometry gives way to an intimacy with the painted mark.

In short, the British always have a past, even with a new-media artist like Tacita Dean, who turns movingly to older artists on video. In America, Modernism had to create its own arts establishment, apart from existing institutions. Only now are Americans starting to emerge pretty uniformly from university departments. Modernism also stood at a remove from America itself.

Consider how each nation responded to "Sensation," that show of Young British Artists. The exhibition in London had to protect visitors from the Chapman brothers, whose sculpture brings together children and sex. Americans are used to that association from advertising, where a sucker, one might say, is born every minute. They got angry only when art did try to instruct. Chris Ofili had plenty to say about politics, cultural values, and religion, and politicians called it blasphemy.

Like Millard, critics assume that the Britpack has turned things around. They have put art on London's map. Perhaps, however, art was there all along. Some tastemakers just decided at last to unfold the map before getting to work.

Making a fool of oneself in public

Look again at some of the galleries. Hirst can easily look the most traditional of all. He plays out his rebellion in public, not unlike Whistler. He recycles Postmodernism well after Jeff Koons and others had already recycled Pop Art's recycling of advertising's recycling of the reproducible. At the same time, he adds intimations of immortality.

For Hirst, careerism does not conflict with matters of life and death: It depends on them. No wonder the press eats him up, while many Americans and thoughtful British friends see only Pop Lite.

One sees elsewhere much the same concern for the arts establishment and for meaning, anticipating debates at the Royal Academy over political art. I see it in Currie's conservatism and human themes, even as he approaches abstraction. I see it in Julien's narrative structures in video. Even Oliver contrasts tellingly with American art. The very same month in New York, Paul Kos stacks circles almost exactly the same way, but for the illusion of a red pawn. Where Oliver clings outward to physical beauty and inward to the human condition, the Californian keeps his emotional distance while giving his art a political context.

Jankowski's commentary sounds funnier, but it too has a certain insularity when it comes to the British arts establishment. He turns his witty eye on the art world itself, questioning fame, marketing, and critical jargon. He presumes art is a public culture, to be looked at. At the same time, I could not help noticing that his pretend interviews parody mostly American artists. Hirst can sleep soundly after all.

All this self-involvement means too many exclusions. Still, it means plenty of thrills. All the walking, the architectural flux, and the creativity makes gallery going at once a physical, an intellectual, a political, and an emotional experience. Besides, I myself would prefer Oliver over Kos any day, just for one. Take that, New York.

Perhaps more important, alternatives do exist. Maybe I had to visit Raimes's studio to see another side of abstract art. Maybe, by sheer coincidence, I had to return to New York for Lethbridge. Jankowski will next show in New York, but far beyond Chelsea. Still, London has a lot more out there than the Britpack. As one nice side of public commitment to the arts, I can hold out hope that much more of it will soon have a chance.

Normally, this Web magazine concludes each article with a list of shows under review, their dates, and links to its page of art resources. There one can find hours, addresses, and related Web sites. However, I fear that I cannot maintain an up-to-date listing for London along with New York galleries and American museums. Indeed, I can only admire the British who attempt it. I shall thus only note that I visited London in late September 2003, and the show in America mentioned, by Julian Lethbridge, ran through October 18 at Paula Cooper. I hope that the British, especially the exceptional artist who showed me around, can put up with the arrogance of naive impressions.