Unfettered Art and the Free Market

John Haberin New York City

After Mapplethorpe: Public Funds for the Arts

Yes, all eyes right now are on the twin evils of gutting Obamacare and tax cuts for the rich, both driving a Republican budget. As I write in June 2017, the National Endowment for the Arts and funding for the arts are once again at risk. Are anger, censorship, and cuts inevitable, and how serious are the threats? Is it just a matter of stupid, self-righteous people eager to take offense?

The question is newly important, with Donald Trump as president, Rudy Giuliani back in and out of the news, and Dana Schutz under fire at the Whitney Biennial for daring as a white woman to express her horror at the killing of black men. Allow me to revisit an essay of mine from more than 20 years ago to ask.

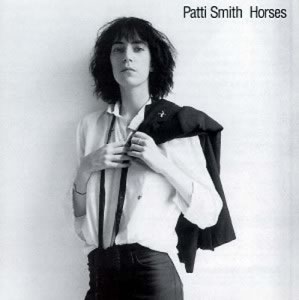

By their very nature, art and the authorities are at war. How, then, can artists ask for a handout? For the right, government subsidies put a stamp of approval on immorality. For many on the left, subsidies mean that institutions will shape ideas, when it ought to be the other way around. For both right and left, the outcries over Robert Mapplethorpe offered a vivid reminder that funding comes with long strings attached.

Yet those strings sustain and connect art to the world. In Mapplethorpe's case, they tug at ready notions of human fantasy, gawking as moral complicity, complicity with the art world, pornography as literature or even as classicism, gays as outsiders, risky sexuality in art, celebrity in portraiture, and the very involvement of art in self-portraiture. Art may be created in isolation and cherished in private, but it is always a public concern. No ordinary goods persistently depend on society's perception of itself. And no other goods cut so intently through perception itself.

As a public matter, art thrives on the confluence between private thoughts and public interest—and public support. Haters of grants and subsidies defend more than a free market and freedom of thought. They also condemn artists to live an ugly, damaging myth.

The myth speaks of capitalism and art in the same terms. That already is a cause for worry. Both alike, the story goes, are the unfettered expression of individual ends, ends given to consumers and artists by their unchanging nature. It just so happens that one is pursuing pleasure, the other alienated, but both contribute to art's carnival. I prefer to live in a market economy myself, but I cannot accept that myth.

Artists tear through myths anyway, even under Lenin and Stalinism. It is part of their work. How strange when ideology offers its highest praise to exactly those artists who determinedly starve to criticize the ideology. Someone is in logical trouble.

To see what is wrong, let me first set capitalism aside. What does the myth say about art? It claims that artists work best constrained by their audience alone. Art has winners and losers, it continues, like anything else. The best artists may at times be losers, but the true genius will always carry on. Take each point in turn.

Even without grants, artists depend on subsidies. They do so indirectly, since cities with a cultural climate bolstered by museums and other institutions have a thriving marketplace for any good. They do so more directly as well, since painters who earn a living often manage by taking a teaching job. That works only because art education depends, quite properly, on public funds—just as it did when education came in the workshops of history's greatest artists.

But artists have always depended on public largesse. Many great cultures, like Mozart's, were partly aristocratic, in which case private funding was government funding. With huge museum gifts today as tax deductions, institutions again blend together. Perhaps they should. When powerful banking families in Florence failed shortly after Giotto's time, it took nearly a century of small-scale art before the Renaissance could fully burst forth. It took an age finally ready for public art on a grand scale.

Good art demands an audience. An audience enriches art—because art serves as communication and as representation. An audience becomes part of the work's content, as I admit when I identify with a character in a novel. An audience allows artists to make their description of the world concrete. And yes, it does sift from among works. Even when an artist decides to ignore or insult those constraints, they are acknowledged.

Yet the need for a public hardly contravenes public support for the arts. Here is yet another sign that capitalism comes with many myths, in this case the bureaucrat selecting art for us. In real life, government supports the arts by funding private groups, so that they can better inject variety into the public's choices.

I mentioned government support through museums and schools. Direct grants to artists and collectives are a far smaller chunk of arts funding than the myth allows. Even private charity has a subsidy through tax deductions. As an unapologetic elitist when it comes to art, I take comfort in the higher standards that all these public and private institutions can set. Most often, however, they contribute not so much by making choices, but by sustaining choice where sustenance is desperately needed.

Again, the myths break down. If a museum can afford more different kinds of exhibitions and can lower admission to a few dollars so that more of the public will attend, the market has not ceased to function: it has only just started to function efficiently.

The market works best for the arts in a stage when it is most unfettered. However, unless some outside force intervenes, that stage passes naturally, just as any market segment is lost over time to mergers and consolidation. Broadway and then in turn Off-Broadway had their golden ages of creativity, as did AM and then FM radio. None of those ages lasted until today.

The same awful consolidation comes to any market. It ceases to allow audience choice, because the cost of access becomes too high.

Impressionism may not have been funded, at least after Napoleon III ordered the Salon des Refusés, and that is terrific too. Degas's wealth helped to create the avant-garde. Yet that only confirms that the starving genius is a cultural product and a historical phenomenon. It is not a moral or psychological fact of life. Art will continue whatever happens, but every decision, even the choice not to intervene, is a public decision.

Maybe the finest art of all really is popular art, like Shakespeare's theater with its cheap seats, but praising contemporary America is not going to make popular art any more possible. It may take public intervention to keep even private art markets free and alive.

Yes, the arts and the marketplace work the same way. But that is only a reminder that in economics too words like public and private never exactly mean what they say. If government-sponsored roads and home mortgages had not permitted postwar suburbs, we would not say that the market had chosen styles of housing more effectively. Imagine if voting cost a small fortune. No one would call America more democratic.

Just 15 years ago, before Reaganomics, the purist description of the market system was an eccentricity hardly worth refuting. Capitalism hinges on laws to promote, restrain, and subsidize transactions. I see no reason that artists should be any purer.

The arts and the free market alike depend on change and diversity, just as any moral action depends on understanding the role of diverse opinion. In all that diversity, a relatively elite audience can be every bit as vital as a large one. Talk about "winners and losers" or "survival of the fittest" only obscures matters. A Baroque opera at the Brooklyn Academy of Music is hardly a loser for having a smaller house than a rock concert. Both can be valid art forms, and both sell out. They are surely both winners. Or perhaps we are supposed to think of Hollywood blockbusters as the ultimate art form.

In the end, the losers may well write history, but not on their own. In fact, artists are by no means so eternal in their gut instincts as the myth suggests. I miss plenty of promising artists who have been sidetracked for good. Even the very greatest artists can be destroyed. Boccaccio renounced The Decameron and converted. If personal distractions can be that powerful, I have no doubt that threats of starvation lose the world at least a few decent artists, too.

I said that the lines between public and private blurred long ago. Ayn Rand's supporters may conjure up bizarre fantasies of vicious laws. Other critics of subsidies may simply call for an audience and an artist to have their say. They disagree violently, but they are both trying vainly to hide between the blurry lines as if they were steel walls.

Government support for the arts does indeed come with strings attached. But myths of a free market leave more than just lovers of the arts in chains.

"Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment" opened at the Institute for Contemporary Art in Philadelphia in late 1988. It came to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center before the Corcoran in Washington withdrew, ending a planned seven-city tour.