Coming Soon

John Haberin New York City

Do Openings Still Matter?

Enjoyed the relaxation of those late August weeks without openings to attend? Did you skip town to avoid even the thought of art? Or were you already geared up for fall—or just plain dreading it?

Speaking for myself, I come closer each year to the last. That first week or two after Labor Day comes as a rush and yet also as impossible to manage. No one can see or remember it all. No one can know what to expect without days of pounding the pavement and surfing the Web. And that is what I found myself doing, when any sane person would be taking a summer break. I learned more than I expected about the art world as well, from seeing others hard at work, too.

Oh, I know, maybe all this hardly matters nowadays. Some observers, not to mention collectors, may well skip openings entirely, along with the exhibitions. As of 2013, The Times reports, more than a third of a dealer's business on average comes from the perpetual art fairs. A third, that is, in dollars, not volume—and I leave it to you to figure out what the difference says about which end of the market keeps up the bulk of the buying and selling.

No one can get to know art and artists that way, although fairs have tried all sorts of things to get people to stop and look. As usual, though, things are more complex than may appear when it comes to matters of the politics of art—and a postscript returns to the politics in light of fall news about forgeries and auction prices. Openings may indeed still matter, but if auction prices matter at all, to whom?

The tangle and the world

Even a single-artist fair booth depends for attention on the artist's and dealer's clout, but that does not make art all about money. For one thing, the ordinary business of a gallery in discovering and promoting artists legitimizes the art fairs, some one hundred years after the original Armory Show. In turn, global attention helps legitimize the gallery. Top critics reported back from the Venice Biennale with much the same excitement as from the shock of the new. Still, fairs only add to the enormous costs to struggling and established players alike. And that puts serious pressure on anyone gambling on the new and on "slow art" while hoping to stay alive.

In other words, galleries still matter, but it gets harder and harder to disentangle art and commerce or beauty and smarts. If that sounds sad, it should also get in the way of cynics attempting to reduce one to the other. In real life, tangling and untangling is part of how art works. The usual outrage, panic, or celebration at auction prices hardly matters to more than a handful. Top dealers competing to set the record for gallery square feet do matter, because they reduce art to a clinical specimen or a carnival. Yet that observation, too, quickly becomes a lazy way out of learning about others—even when, fittingly, reports appear in The Wall Street Journal.

The tangle extends to motives and media within the art. One can no longer so easily describe a great deal of terrific art as abstract or representational, painting or prints, conceptual or material, personal or political, insider or outsider, high culture or low. Rather than the snobbery or critical distance of the "Pictures generation," one gets a return to pleasure, and it is impossible to say how much that return drives or derives from art's larger public. Is it enough to say that anything goes? Is it enough now to accept good art as neither complacent nor corrupt, but an ordinary part of the world? Maybe not, but art of the past, too, depended on ideology and patronage, without speaking as a mere voice for either one.

And the tangle affects everyone. Now no one gets to shut down for the summer. One dealer said, with something between a smile and resignation, that she allowed herself a week, and she hung her fall show before she left. Others were staging brief solo exhibitions, either to raise money from a subtenant or to stay in touch with clients. Several were closed, but for installation rather than for a break. A few were in work clothes and breaking a sweat, for the move to a new and larger space.

Much as after Hurricane Sandy or Covid-19, not everyone can afford to delegate walls, floors, and lighting to the hired help. Yet everyone feels much the same pressures, if only on a more modest scale. One can see the urge to move upward in two galleries that closed shop entirely. When Jessie Washburne-Harris and Michael Lieberman exited after seven years, some lamented the economics that led to closure. Yet they had two stellar years on West 26th Street, as something of a critical darling, and the former immediately became a director at Metro Pictures. Meanwhile John D'Amelio shut an equally successful Chelsea space to help guide David Zwirner.

Much as after Hurricane Sandy or Covid-19, not everyone can afford to delegate walls, floors, and lighting to the hired help. Yet everyone feels much the same pressures, if only on a more modest scale. One can see the urge to move upward in two galleries that closed shop entirely. When Jessie Washburne-Harris and Michael Lieberman exited after seven years, some lamented the economics that led to closure. Yet they had two stellar years on West 26th Street, as something of a critical darling, and the former immediately became a director at Metro Pictures. Meanwhile John D'Amelio shut an equally successful Chelsea space to help guide David Zwirner.

They also reflect the closed circle of marketing and compliant media. "We see this," Washburne-Harris announced, "as a moment of opportunity for us in our individual professional lives." A year earlier, on splitting with his partner, D'Amelio was quoted as finding his way back to a younger self just starting out. Now he described himself as "spreading his wings." Not that one can escape the closed circle through the smaller communities of the outer boroughs. More firmly than ever a franchise and not an alternative, MoMA PS1, once "not for sale," will start the fall with an extravagant and often-exhibited Gagosian artist, Mike Kelley.

Why they are called artists

I received a press release the other day. At least I think I did, unless I discarded it unread and will never know, but it might have read like this:

Brooklyn's leading venue for needy artists is proud to announce that it will no longer hang work using nails, bolts, or screws. According to its founder and director, the decision pursues the gallery's original vision to its culmination. "We have long thrown up work after work on the wall, just to see what will stick. And now it will have to."

Himself an already forgotten artist, he says that eliminating brackets will set bad art free to find the visual space it deserves. "We estimate that, with the extra space not dedicated to hardware, we can now fit at least 400 works into a single show, and one of them could be yours, or mine." Previous estimates limited group shows to only 350, as for Sideshow, including lining the ceilings.

"With the move of Storefront out of Bushwick," he added, "this should solidify our hold on the worst of Brooklyn art." L magazine and the Brooklyn Rail both refused to comment, citing their allegiance to all studios and galleries that agree to name them as definitive culture critics. Both have listed the gallery as one of ten essential stops for those in the know, assuming you can count that high.

Okay, I made that up, but even DYI is all about networking, just with a different network. It says something that one of Brooklyn's most popular artists made his name taping Chelsea openings, and his text paintings depict actual networks of artists. So many years ago, Alfred Barr's chart of "inventing abstraction" meant a new means of visualization for a new art, at once more democratic and more polemical. Ad Reinhardt meant his art comics as funny and yet definitive, in a context of modern art's coming to a premature end.  Marc Lombardi meant his charts to stand for opposition to insider status, and William Powhida means his as summing up them all—as definitive, dismissive, and hilarious. Now one has a painter who defers to what its audience knows and expects, in order to build a career and an ego.

Marc Lombardi meant his charts to stand for opposition to insider status, and William Powhida means his as summing up them all—as definitive, dismissive, and hilarious. Now one has a painter who defers to what its audience knows and expects, in order to build a career and an ego.

That is why I keep arguing for midlevel dealers and what they contribute. Think of the term as shorthand for pretty much everyone outside 24th Street, because supposed trends and alarms alike that name only the fancy few are highly overrated. The dealers I mean can no longer play the role that Paula Cooper or Leo Castelli once played, to name just two of my heroes, as Elizabeth Dee has argued, because the plot itself has changed, without an "avant-garde." Yet they can offer the same dedication (and, often enough, a solid business model). Just ask Richard Serra (in an interview with Hal Foster). The sculptor was talking about art in relation to architecture, like his own work at the Guggenheim in Bilbao, but he could have had in mind the state of art today:

Art has always found ways to intervene, to critique . . . , to transform, and to transgress space. Artists will continue to do that. They understand the contradictions. Can they find a way not to serve . . . interests completely, and even to override those interests through the intensity of what they project? For sure they can: that's why they're called artists.

Maybe Serra is way too optimistic, but that is why he, too, is called an artist. Openings are, in more ways than one, where it all begins. See you there! Unless, of course, one of us loses heart. Not that I am suggesting it. But then there is always another press release.

A postscript: were you fooled?

Some news from the art world can drown out the day-to-day experience of fall in the galleries. And that may be far worse than the news itself. Even if you cannot find your way around the Lower East Side, you surely heard that a triptych by Francis Bacon sold at auction in November for $142.4 million, in a contemporary art sale of $691.6 million. For all most of us know, it could almost have been Monopoly money. You probably heard, too, of how forgeries brought down a dealer that helped put some of the best American art on the map. Only the second is criminal, at least literally, but both stories left a bad taste.

They also left some very smart people wondering how things could get so out of hand. At The New Yorker online, Peter Schjeldahl brought his usual much-needed dose of reality, much as with the spectacle of auction prices or art and money. Were the forgeries of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and others really good enough to fool the experts, and should that success give one pleasure or give one pause? Not everyone, he points out, was taken in by the forgeries (and, yes, attributions matter). Another critic, Carol Diehl, on Facebook of a friend's being asked what he (of a distinguished gallery family himself) thought of the Rothkos at an art fair. Why, he replied, What Rothkos?

They also left some very smart people wondering how things could get so out of hand. At The New Yorker online, Peter Schjeldahl brought his usual much-needed dose of reality, much as with the spectacle of auction prices or art and money. Were the forgeries of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and others really good enough to fool the experts, and should that success give one pleasure or give one pause? Not everyone, he points out, was taken in by the forgeries (and, yes, attributions matter). Another critic, Carol Diehl, on Facebook of a friend's being asked what he (of a distinguished gallery family himself) thought of the Rothkos at an art fair. Why, he replied, What Rothkos?

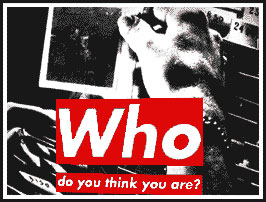

Maybe that just states the obvious (and, oh, the jpg here is not a forgery). A much-loved gallery soon found itself out of business, because plenty of others were not taken in, not even briefly. A dealer was fooled, but people often believe things if their livelihood depends on believing. Who can say when stupidity ends and venality begins? Just as important, most of us could not have been taken in, because we never so much as saw the forgeries. The real lesson of the headlines is how little they say about artists, dealers, and the public for art.

I loved Knoedler. For years, I went there eagerly, to learn about Frank Stella and so much more. If the gallery were putting material out there with the name Rothko on it, I would have headed there breathlessly—and so, I suspect, would you. Would we have been taken in? Maybe, but it says something that we never had the chance to find out. The alleged discoveries merely fed a burgeoning high-end traffic for international clients.

That traffic also drives the auction news, which Schjeldahl rightly dismisses as "the circus," and it explains why I could hardly care less. Clients may know and trust in little more than a dealer's advice and an artist's name. It helps that Bacon is the most old-fashioned of late modernists, with an overt agony and not so very covert realism that can engage anyone. A triptych itself announces ambition. Yet one can do better than to argue whether to call high prices signs of fraud or greatness. Rather, it is well past the time to stop worrying about a few exclusive galleries and about auctions, period.

That kind of news gets way too much press and, for the rest of us, way too much admiration or resentment. The "big four," as Jerry Saltz calls certain galleries, are consuming a critic as passionate as he, but they say pretty much zilch about the state of art. Not that commercial pressures at the high end do not trickle down, altering how all galleries and museums work to build an audience. It is a story worth remembering—but sometimes one just has to forget it. And now I shall prepare for a visit to Chelsea tonight and to the Lower East Side tomorrow. I may enjoy myself, and I may actually learn something.

The New York Times reported on fairs and finances on August 21, 2013, and The Wall Street Journal on competing numbers of gallery square feet on August 30. Hal Foster's interview with Richard Serra now appears in The Art-Architecture Complex (Verso, 2013). Peter Schjeldahl blogged on November 8 and November 13.