Starting Over at Eighty

John Haberin New York City

Alma Thomas and Rosemarie Castoro

In her work as in her life, Alma Thomas displayed a stubborn optimism. How astounding to recall how long she had to struggle to maintain it. Even a retrospective at the Studio Museum in Harlem catches her only as she is about to run her victory lap.

It follows a Tribeca gallery's recovery of another woman artist working in those years, Rosemarie Castoro. She, too, started afresh more than once after 1960, although unlike Thomas she never reached her eighties. If Castoro belonged to a different movement and a different race, she knew exclusions as well. Like Thomas, she also knew about reconciling repeated elements and a heightened subjectivity.

Concentrating on color

"Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man's inhumanity to man." Alma Thomas could concentrate on the scene before her eyes, with inspiration from the garden outside her window. She could take quite literally the long view, imagining the same scene from outer space. Most of all, she could concentrate on paint, with a gesture as simple as pushing a brush against canvas. Repeat often enough, and subjective experience becomes a regular array. All of these translate into points of light, against a background of still more color or white.

She started concentrating well before she found that signature style, with only a brief turn aside. In 1964 she took hope from the Civil Rights movement and painted its marchers, as a cloud of white against the darkness—and then she returned to her business in abstraction. Let others concentrate on the obstacles to a woman in art or to an African American every single day. Let others argue, too, in those contentious years over claims to Modernism or the very nature of art. She preferred to dwell on possibilities and to create them in paint. In the process, she confronted barriers every step of the way.

Born in 1891, Thomas moved with her family from Georgia to Washington, D.C., as a teenager—as part of the Great Migration and the flight from the American South, a subject for the Studio Museum itself not so long ago. She showed an interest in art both at home and in high school, but after graduation she found herself teaching kindergarten. She entered Howard University only at age thirty and even then for home economics, before shifting her major to art, a first for Howard. She completed her MFA at American University, but only after further studies at Columbia University Teachers College. Her education gave her an early exposure to modern art, and she took it seriously. She admired Wassily Kandinsky and Henri Matisse, although they enter her mature work less as styles than as a dedication to abstraction and to color.

One can only imagine how much she saw and how much she knew. She was nearing sixty when Jackson Pollock had his greatest fame. She was also apart from the action, although a new Washington Color School was just coming to the fore as well. It includes Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, although she insisted on her brush rather than soaks, stains, or drips. It includes another African American, Sam Gilliam, whom she approaches with all-over paintings, but with greater discipline and a greater openness to white. Although not a color-field painter, E. J. Martin worked in Washington on his Cubist compositions as well.

Still, she had a traditionally woman's career in teaching, and she had her breakthrough only on retirement from Shaw Junior High in 1960. Did she need to need full time in order to succeed? At the very least, she could now concentrate on painting of and from space. She had her first major exhibition at her alma mater six years later, and she found her direction just in time. Maybe the show helped provide the impetus. She called the series "Earth," but she is looking at last directly ahead and up.

Daubs of paint fill a rectangle or circle. They stick to bright primary and secondary colors, but with room for the white beneath them to breathe. They fall in verticals of a single color, sometimes with verticals of the same color clustered as a field. A lone yellow pillar might further disrupt the rhythms and the symmetry. Titles refer to tulips, jonquils and crocuses, and Thomas spoke of the holly tree outside her window. Yet the work has only now become so fully a matter of color and so fully abstract.

Out of the shadows

The color fields grow in strength in the early 1970s, as she thinks of the view from the space program. One title, Starry Night and the Argonauts, suggests an update of Vincent van Gogh and myth for an entirely modern journey. Maybe it matters that NASA's moon landing marked one of America's last moments of shared optimism. Her very process consists of one small step after another for a woman and one giant leap for her art. She had her Whitney retrospective, the first ever for a black woman, only at age eighty—six years before her death in 1978. And she was still finding her way.

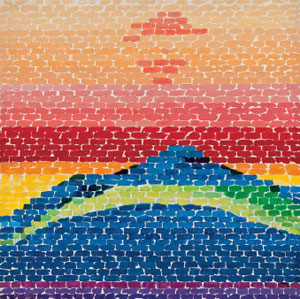

By the end of the decade, the daubs have become her "Mosaics." Some paintings transfer the underpainting to the top, with slits for color standing for cherry blossoms or stars. The grandest of all settles on a single tiling of red. One may see the influence of Matisse cutouts, with the broader colors and the craft. I prefer to think of Lee Krasner, Krasner in collage, and the tactility of actual mosaics. Regardless, Matisse and Thomas each gave one last shape to the narrative of a life.

One can point to other antecedents as well. A painting from 1959 looks much like the French version of Abstract Expressionism. As for Nicolas de Staël, impasto and an easel scale mute the impact of color and gesture. Thomas at the time looks freer and brighter in watercolor, closer to Joan Mitchell after all, but her own color-field painting was still to come. Her daubs and reminders of nature may recall Impressionism or Pointillism, but with an overriding geometry and the visible marks of her brush.

The Studio Museum exhibits only twenty paintings, as "Color in Shadow," plus works on paper from the Columbus Museum of Art. I called a larger exhibition in Chelsea the best of 2015 that I failed to review. Her gallery, Michael Rosenfeld, also contributes a handful of relatively early work here. While that show blew me away, this one goes about making sense of her career. It does not worry about her until nearly 1960, and it has significant gaps in her late work as well, but it puts everything in some semblance of order. And that takes bearing in mind what one cannot see.

Was there ever a uniquely black abstraction, from her and Vivian Browne to William T. Williams and Sanford Biggers today, or a woman's art? She would have to say no, even as her life speaks to her achievement. The Washington school includes other women, too, although she could not follow Anne Truitt from color into Minimalism. Thomas worked with regular elements, but she could not reduce them to anything like a formula. Sketches look less like prescriptions for a painting than throwaways. Still, she shared with another woman in Minimalism, Castoro, a belief in small steps out of the shadows.

At her worst, the daubs suffer from their regularity and a surfeit of red. At her best, they reward a concentration on color like her own. One fiery painting reduces the daubs to a circle of red, yellow, and orange, surrounded by still more orange. The garden greens have gone. A larger show might have had more variations on a theme and a greater context in time, but at least this one heightens her need to concentrate. It took her a lifetime for her colors to grow.

Arch support

For an artist who all but disappeared from the art news, Rosemarie Castoro made at least one striking late appearance. One can see her in a photo, blurred by the long exposure, striding or maybe dancing past sculpture that could be striding or dancing itself. One might never know that the artist and dancer had entered her sixties with the millennium. In the Arched Waves of welded steel, successive folds add up to two feet on the ground but arching into space. They might almost update Italian Futurism for Minimalism and its dreams of pure form. But then Umberto Boccioni did call his 1913 bronze Unique Forums of Continuity in Space.

Not that Castoro ever quite disappeared, thanks to steady support from her long-time Tribeca dealer. She was intimate with Minimalism's first circle in the 1960s, and her work makes little sense apart from it. A large red painting dates from 1964, roughly the time of Frank Stella in black, aluminum, copper, and color. Bright red lines outline fields of a softer red, much as the gaps between Stella's stripes define his canvas. The repeated curves of her Trunk Tracks, close to tongue lickings, fill rectangles much like typewriter drawings by Carl Andre. Drawings based on parallel lines recall Sol LeWitt.

Not that Castoro ever quite disappeared, thanks to steady support from her long-time Tribeca dealer. She was intimate with Minimalism's first circle in the 1960s, and her work makes little sense apart from it. A large red painting dates from 1964, roughly the time of Frank Stella in black, aluminum, copper, and color. Bright red lines outline fields of a softer red, much as the gaps between Stella's stripes define his canvas. The repeated curves of her Trunk Tracks, close to tongue lickings, fill rectangles much like typewriter drawings by Carl Andre. Drawings based on parallel lines recall Sol LeWitt.

Still, she took her share of hits as a woman and her share of neglect, long before her death in 2015. A look back at her career came as news, in fact, to me. It also comes at a time of greater interest in recovering figures from that generation, including women like Phyllida Barlow and Sheila Hicks. Castoro appeared in an experimental film with Andre and Lee Lozano, who similarly fell off the radar in the 1970s. Still, surely part of her invisibility has to do with a refusal to play by the rules. Back when art was so often rule based, that had to be a big deal.

Castoro embraced irregularity. Diagonal bands in graphite from 1966 cross each other every which way. Paintings from the 1960s may build on a single element, such as the letter Y, like alphabets for Richard Tuttle. Yet the big red painting is more like a jigsaw puzzle. She favors optical activity over conceptual rigor in "pencil paintings" from 1968, where diagonals in several colors of pencil on acrylic create a single vibrant field of blue-gray. She also has an obvious eclecticism, across media and strategies. Even in graphite, she saw herself as working in, not to mention covered in, dust.

Just as much, she moved between two and three dimensions as if they were one. In Rotating Corners from 1971, graphite darkens panels some seven feet tall, like the triptych leaning against a facing wall. Only here the panels stand at right angles on the floor. While diehard supporters may prefer work from the 1960s, her move toward sculpture continues for some forty years. Torched stainless steel from 1985 already has its share of twists and turns, as well as a depth of dark color from the torching. A wire sculpture appears the next year, and soon enough gesso lends graphite on paper and board the firmness of papier-mâché. The shift brings out the illusionist in her as well, as in large, richly shaded drawings of even more twisted sculptural forms.

The shift also brings out a susceptibility to allusion, most often to something between spirituality and nature. Titles refer to Venus, Erda, and of course trunks and waves. It has to say something, too, that those are female gods. Still, Castoro has not gone altogether misty-eyed, not when arches also refer to architecture. Maybe her mind was on too many things to come up fully to her more famous peers. Still, the vigor of her eclecticism has lessons for the chaos of art today.

Alma Thomas ran at the Studio Museum in Harlem through October 30, 2016, and at Michael Rosenfeld through May 16, 2015. Rosemarie Castoro ran at Hal Bromm through July 29, 2016.