Moonlight Becomes You

John Haberin New York City

Caspar David Friedrich: Moonwatchers

Anita Brookner: Romanticism and Its Discontents

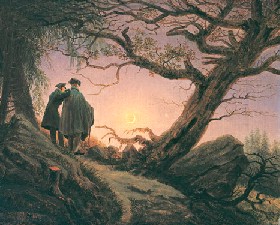

Two men gaze through a wood at the moon. They may have turned to the forest for a connection to the night or for the sounds, smell, and light of nature buried in the sweat and toil of day. They could have sought each other's intimacy, in the quiet of the night—apart from conversation that hardly knew when to stop. They have no weapons, but they could have sought adventure, swaggering in their broad hats and capes, confident in their powers to bring down their prey.

It hardly matters. Earthly quarry come way too easily. These men are in fact students—of the physical universe and the soul, the painter himself and a friend. They have stopped in their tracks, because they seek something farther and less attainable.

Instead of a fox, an idea, or the earth, they have gained clearing, and the moon stops them dead. The painter, Caspar David Friedrich, exaggerates a rise in the wood and distance to the sky with a low vantage point. He heightens the ghostly light with a color and shadow almost out of forest scenes in Bambi, if not out of a German tradition going back to at least the Northern Renaissance and Matthias Grünewald. Like the men but more literally, Friedrich steps quite out of physical space. He puts their motives aside, turning their backs to the picture plane. Now only the painter's feelings count.

The painting appears in a haunting, well-chosen concentration. To help celebrate a new acquisition, the Met assembles two paintings by the German Romantic, several drawings, and a handful of other work showing his influence. The Frick Collection has shown repeatedly how much more a small show can bring home than many an overblown retrospective, and the Met's restraint makes a familiar but elusive image fresh and intelligible. It may still run to hard-edged emotional overkill, but it is impossible to forget. If any painting could represent longing for the unattainable, this must be it.

Moonlight and chilly air

Infinite longing. One expects a decidedly romantic idea of Romanticism after loose talk of Friedrich and souls. It also just happens to define Romanticism for Anita Brookner. Romanticism and Its Discontents puts the emphasis squarely on the discontent. Her introduction to nineteenth-century French art and letters, now in paperback, comes off all too pat and Romantic itself. Still, Romanticism truly deserves a survey as heartfelt and concise as this one.

The term Romanticism comes from romance, from the exotic allure of period fiction. So it may make sense that most will know Brookner first as a novelist. Yet she also lectures in art at the Courtauld Institute in London. (Many a modernist has pilgrimaged there to see A Bar at the Folies-Bergère by Edouard Manet.) Her previous art-history books have taken up the century of the Rococo, the French academy, and Classicism. Now she works her way up—to a defining moment for culture ever since.

A movement so epoch-making may sound like an easy success. For Brookner, though, Romanticism means dealing with failure—and failing badly at the attempt.

She starts with a quotation she likes so much that she repeats it four times in as many pages. Let me settle for just once: "Mais, M. de Voltaire, vous combattez et détruisez toutes les erreurs, mais que mettez-vous à leur place?" But, M. de Voltaire, you combat and destroy all the errors, but what do you put in their place?

After an introductory chapter, easily the least convincing, she gives a chapter each to some of the leading lights. With a novelist's eye for character and telling detail, she ranges from J. B. Greuze and Eugène Delacroix in painting to Emile Zola and the Goncourt Brothers in prose. Her cover image and opening chapter single out the tricky but compelling case of Anne-Louis Girodet, a student of David who never lived to see Romanticism thrive but anticipated many of its themes.

Her half-dozen creators represent as many ways to cope with uncertainty. Some escape into idealism, art, and the Classicism of their teachers. Others look to determinate causes in science and humanity. Most found a hero in Napoleon. Each ends up with hardly more than a struggle, fatigue, and fancy ideals to which he himself puts the lie. Or so goes Brookner's chilly romance.

Woe is me

Romanticism has had no shortage of definitions, starting with those of its founders. In England, William Blake had no hesitation denouncing anyone unable to grasp his universal principles of religion. William Wordsworth's preface to Lyrical Ballads came as a manifesto for poetry, as "a man speaking to men." In between the poetry and drugs, Samuel Taylor Coleridge made time for intricate theorizing about art's role in "humanizing nature," proclaiming beauty in "the abstract, the unity of the manifold, the coalescence of the diverse." Brookner includes critics as influential as Charles Baudelaire, who fought for "the painting of modern life," and Emile Zola, who felt the duty to champion Alfred Dreyfus and the working class against racism, financial power, and corrupt government.

Modern critics have opposed Classicism to Romanticism, using more contrasts than I care to remember—linear versus painterly, theater versus absorption, wilderness versus culture, primitive versus pastoral, authority versus community, aristocracy versus big industry, villa versus garden, and goodness knows what else. Perhaps only manifestos, historians, and art critics believe in periods anyway. Rebels against Jacques-Louis David, Monsieur Voltaire himself, and Denis Diderot kept the revolutionary ideals of the first, the skepticism of the second, and the irony of the last. Nicolas Poussin and Poussin's landscapes take Classicism into the Baroque with all its temptations intact, Delacroix paints like a Romantic while proclaiming his classicism, and J. D. Ingres echoes David's line and idealized virtues while adding electric colors and an arm that manages to grow out of a sitter's chest. One could debate forever whether Modernism ever outgrew Romantic individualism and a culture of capitalism.

Brookner is at her best in the diversity and individuality of her portraits. Her discontents earns its plural, and Brookner is good with words. She can take an artist long ago reduced to an emblem and draw out divided loyalties. I took my best examples just now from her. She also starts right out by insisting on what Romanticism is not.

Forget all those proclamations, for she excludes Blake as one of those "false Romantics" who "strike poses." Forget feelings, for true Romantics command deeds. Forget generalizations across nations, for only France had the shock of revolution, then terror, Bonapartism, and reaction that makes for a stark divide in art and a public struggle. Forget style or subject matter. In a brief foray outside France, she uses Friedrich as an example. He does not represent religious longing, as with a cross, but sets it on stormy seas.

Only one trouble: that leaves a cliché, what she herself calls "the great commonplaces." Infinite longing, the unattainable, and certain failure—they make me want to throw the back of one hand against my forehead, although I should never throw a book this engaging at the floor. I can almost hear all of France sighing in unison, "Woe is me. Alas."

Oddly for a novelist, the generalization brings one no closer to causes either. Other than Napoleon's defeat and a crisis of belief thanks to Voltaire, she has no interest in a world outside of art. Someone like Zola might study genetic factors and industrial society, but remember: he fails completely. One starts to long for my long list of critical categories. At least those writers lived in society.

Living in uncertainty and blood

What exactly has gone wrong? What has made her portrait of an age so attenuated? In part, she just gets carried away with her own virtuosity. As with the quote about Voltaire, she sometimes repeats phrases once too often.

From the very start, too, one has signs that the argument will get slippery. If David has Romantic tendencies but Blake has none, anything goes. All those denials get awfully circular, too. Feelings do not count, only actions, while Friedrich puts aside facts for feelings. Or look again at the German painter, with that example of religion on the high seas. Brookner's escape from both formalism and iconography leaves her with a curiously empty idea of subject matter. Somehow, it does not encompass imagery.

She is at her most evasive with the notion of failure. It fits far too much. Greuze won every honor, but he still chased after David. Delacroix drawings find heroism in the gritty, human reality of real war, but ugh, those dead bodies and drops of blood. Baudelaire wasted so much time as art critic that he completed only the most significant verse of his time—plus a beautiful volume of prose poems she does not mention. Zola deepened his insights to capture broad social forces, wrote at a breakneck pace, and turned the Dreyfus affair right around, but it exhausted him, and his early determinism had failed him.

Romanticism did not invent crises in belief, and it did not conclude them. One historian used a longing for authority after plague to explain art of the 1350s, and last I looked people still mostly believe in God. Modern art still shocks. When Brookner says that "the Romantic painter . . . is out to remove the spectator from his normal or appropriate perceptual field," she has a pretty good definition of Modernism since Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and Postmodernism as well.

Nor did Romantics lack for confidence and certainty. Brookner's studies provide plenty of examples, but not all of them wanted enough certainty to feel disappointment. Some, like John Keats, joined complexity and composure. Keats tired of Brookner's moi, that "personal anxiety" and "windswept isolation." Art has to be "capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason." Infinite longing, takes a lot of reaching.

For me, a key moment came with Delacroix's sword glistening with drops of blood. (It earns a color plate to itself.) Delacroix felt pain at suffering, but it only increased his admiration for a hero, for it put natural events in human terms. Elsewhere, Brookner notes a gesture drawn from religious art. She sees only a loss of faith in God, not a renewed trust in the secular.

Scientists and tourists

Wordsworth got more pompous as he aged, not to mention more successful. Yet he still sounds relieved, content, and exhilarated in his newfound conversation. Only people observe and value nature, for only people have imagination.

For the poet and others of his time, this serves as an active power—and so a model for the literary art. The imagination, for him, does not stop at taking nature's imprint. It connects humanity and a God-created world. It drove John Constable to his endless cloud studies, George Stubbs to his horses, Camille Corot in search of leisure time, or Gustave Courbet to his newfound gravity in the living or the dead.

Look again at Friedrich's lunar vistas or the sea for Peder Balke, with a dark clarity still visible in landscape art today. The Met makes it dead clear how much he and his countrymen celebrated not the unattainable, but a world newly at hand. One enters past maps of the lunar surface of incredible precision and beauty. Friedrich knew a little astronomy, too, when he included a ring around the moon. Earthshine, reflected light, makes visible just slightly more than half the moon. I imagine that scientists then would have told me just how much more.

The exhibit has just over a dozen paintings from Dresden artists and a couple of works on paper. A motif of two figures turns up again and again, but not just off in the woods. More often, the two, most often a man and a woman, take an evening walk along an urban waterfront. They—and the painters—find comfort in enveloping twilight and a spindly pattern of masts that fills the air. They have come not as daring explorers, but as lovers and tourists caught up in a decidedly humanized nature. How nice of the moon to cooperate.

Not every painter here sticks in one's mind. Even Friedrich's quick drawing and blurred atmosphere work best when he has a great image, like those two men in moonlight. As usual, too, the Met's insistence on annotating every work runs to clichés. It hangs the three versions of Friedrich's Moonwatchers, but not chronologically. It places its own new acquisition in the center, to make clear it is celebrating itself first, not the Dresden school. Besides, that one has the biggest frame.

The Met brings to life an easily forgotten corner of Romanticism—and a painter's calm and careful study of at once humanity and nature. One sees how much a good story mattered to Friedrich, almost like a Surrealist later on. Once he had his Moonwatchers, he changes the light and even the color scheme, with a version in deep nighttime blacks. However, the shape of trees stays put, even down to a beautifully observed pattern of roots. It reminds one of the care with which the astronomer had mapped the very moon.

Romanticism as a novel

One sees, too, what really drove Friedrich's men to the woods. Nature lay close by, even to a city boy—too close by. Progress threatened to uproot nature, just as a massive tree trunk stands torn from the ground and erosion has left a protruding rock to survive the elements. It threatened to break forever the intimate link between humanity and nature. Fortunately, one still has artists and the imagination.

The same fears and hopes drove Asher Durand to paint the observer's point of view into the American landscape, much as Friedrich took himself and a friend. Durand portrayed Thomas Cole, the founder of the Hudson River School and teacher of Frederic Edwin Church, next to William Cullen Bryant, the poet and editor. He called the work Kindred Spirits, and he meant painter and poet, artist and political reformer, but also both men and the scene before them.

Durand's pair has a lot to know and a lot to lose. With typical American optimism, they stand in front of a titanic valley, and one instructs the other. Friedrich makes his scene closer and yet more spectral. After all, Europe has had to deal with civilization a little longer. He keeps his twosome, seen only from behind in their heavy clothing, more anonymous and yet more intimate. His is the Romanticism not of "To a Waterfowl," but The Student Prince.

They come as a pair, with their feet on the ground within the image, because getting in touch with moonlight entails communing with one another. Moonlight, like the artist's spectral colors, transforms them and the woods together. Another pairing, a V of slope and rock, reaches upward to enclose them. The trees bend to encircle them right along with the sweep of their cloaks, just as a ring encircles the moon.

Perhaps it makes sense that Friedrich often looks quaint or cartoonish these days, if also still a popular favorite. The Hudson River School artist he most influenced, George Inness, can similarly look visionary or simply escapist. Friedrich did understand aspiration and failure. He knew personally Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who retold the Faust legend. Like Michi Meko today, he felt at home in the dark woods and a stranger in the urban wilderness. Life after Romanticism has had to battle the same issues of public identity and personal perception—with considerably less confidence in humanity and nature.

In Anita Brookner's novels, proper English men and women fear an awakening sexuality. That sensuality, state of flux, and fear all color her account or Romanticism, too. I do not want to call it wrong, only woefully incomplete—especially if one imagines the segue from Romanticism into Art Since 1900. In her saga of insufficiency and disquiet in France, she may well have put too much of herself, England, and the shape of her art. But then, what could be more Romantic?

Caspar David Friedrich's "Moonwatchers" was on display with further Dresden Romanticism at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through November 11, 2001. Anita Brookner's "Romanticism and Its Discontents" appeared in 2000. Farrar, Straus & Giroux issued it in paperback in 2001.