Racial Coding

John Haberin New York City

Mendi + Keith Obadike: American Cypher

Robin Rhode

Is American Cypher a formal experiment or a history lesson? Is it storytelling or data mining? Biology or a light show? Maybe all of the above, plus text art and new media.

Either way, the work has earned its title. For the artists, though, the real cipher is race in America. Nor are Mendi + Keith Obadike alone in keeping one guessing. Robin Rhode proves himself a master of disguise in photographs and video, even as he is blatantly showing off. He also seems to be riffing on familiar street culture, until one figures out that he is South African.  As for American Cypher, it may map the genome for all these in the nation's founders, but it is up to the present to decipher.

As for American Cypher, it may map the genome for all these in the nation's founders, but it is up to the present to decipher.

A work in progress

Is there a uniquely African American art? Shows like "Blue Smoke" and "Now Dig This!" keep asking, but they can sure trip up critics like Ken Johnson by answering yes and no. Yes, because black artists, black America, and racism demand attention, but no, because these have entered all of American history and culture. For a few months, though, the question took on new meaning, with stellar shows by El Anatsui, Robin Rhode, and Mendi + Keith Obadike. The first two are in fact Africans, like Onyeka Igwe, with El Anatsuibased in Nigeria, while the last speak of themselves as Nigerian Americans. If the question then shifts to African identity, however, including white assumptions about "primitivism," like LaToya Ruby Frazier in steel country, all three document something contemporary and American.

American Cypher is an ongoing project, much like its subject. (Never mind that, when it comes to affirmative action, the Supreme Court now thinks of racial divisions as ancient history.) The artists released one stage in 2012, as part of the New Museum's online program in cooperation with Rhizome. One can still download its nearly one hundred megabytes. For a little over three minutes, an unsteady tracking shot silently navigates a hallway marked by patches of sunlight on the wall—toward an archway in the distance and a dark cipher behind it. As one approaches, one can make out a brighter note to its right, perhaps a way out after all, and a closed door holding secrets of its own.

Text for the online video, crawling vertically like film credits, promises a fresh start while acknowledging its human cost. It directs one to "steal a branch from a neighbor's tree" and "plant it in your yard," to "make a key out of locks of your hair," and to "draw a family portrait using sweat." It ends with advice to "gaze into a mirror" and then to "paint over its surface"—or rather not quite ends, for new text stops coming well before the video fades to white. For better or worse, one might not even notice the back story without a curator's text as well. That might not be such a good thing, but it leaves multiple, shifting ciphers in black and white. It also leaves the story unfinished, so that biology can be history and not destiny.

For the Studio Museum, the artists have created a site-specific installation, as again a passage between darkness and light. The narrow room is itself something of a passage, and you may come first to flickering horizontal bars projected on an end wall. One might be peeking through venetian blinds, to spy on someone else. Some of the bars will darken, interrupted by a tall letter here and there and by a comforting hum in the air. If it seems to display raw data, like the algorithmic flood of numbers from Charles Atlas last year in Bushwick, more is to come. In time, the binary code of white lines gives way to the familiar shape of the genetic code, a helix.

The passageway in question for Rhizome was in fact the basement of Thomas Jefferson's plantation, Monticello, in Virginia. And now the code alludes to Jefferson's sexual relations with Sally Hemmings, the slave of mixed race whose offspring are still a matter for investigation. Not that one must translate the A, G, C, and T of DNA into an ancestry. Mendi + Keith (a couple, not a mathematical formula) create the helix from sentences, although they are not all that much easier to decipher than the human genome as they spiral slowly across the blackened wall. Additional text on metal plates, as for an engraving, is enigmatic in its own way—as parables of the African American dream. Besides, were the raised letters pressed to paper, they would leave still another cipher, their image in reverse.

Each plate tells a separate story, a search for meaning that spirals wildly out of control. No wonder American Cypher is a work in progress. Naturally one plate begins, "There was a woman." In another, "an architect dreamed of drawing a portrait of our origins" and ends up spouting poison. "Once there was a key," reads a third, but "the doors opened to still more doors." Maybe it was the key to that basement door at Monticello.

Street cred

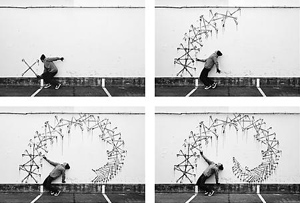

The man in a photograph by Robin Rhode has to look familiar. He may also be the artist, but do not expect him to wait for a greeting. His black shirt, black Keds, and orange backpack could practically serve a street artist as a uniform, and the view from behind could almost serve as a disguise. He crouches by a wall broken by the horizontals of barbed wire, in the act of drawing on it. The shallow, dangerous space brings him close enough to touch, but he is already moving on. So, too, no doubt is the flock of charcoal birds growing and soaring behind him.

He would start to look familiar soon enough anyway, for each photo comes in a sequence, like stills from an imaginary performance video. Move along in Chelsea, and he has already started a new act, in a new but equally familiar disguise. The quick change artist might be taking up a giant feather, a switchblade, or a car increasingly lost in its own motion. Head downtown, to his gallery's Lower East Side space, and three of the birds plus the knife share the walls with him, while the floor holds sculptural boxed sets of charcoal pencils and oil pastels, as comically large tools of the trade. Color wall drawings look like an IT manual for children written by Paul Klee. Not that the knife ever looked all that dangerous, but it sure looks tempting.

He would start to look familiar soon enough anyway, for each photo comes in a sequence, like stills from an imaginary performance video. Move along in Chelsea, and he has already started a new act, in a new but equally familiar disguise. The quick change artist might be taking up a giant feather, a switchblade, or a car increasingly lost in its own motion. Head downtown, to his gallery's Lower East Side space, and three of the birds plus the knife share the walls with him, while the floor holds sculptural boxed sets of charcoal pencils and oil pastels, as comically large tools of the trade. Color wall drawings look like an IT manual for children written by Paul Klee. Not that the knife ever looked all that dangerous, but it sure looks tempting.

In more photos, the backpack now flying off him, he might be fighting with it or against it, wrestling with its outlines as an artist or dancing with them as a man. Not that one can often catch him drawing, any more than the sculpture of human-size compasses nearby, joining in the dance. By the very nature of drawing in sequence, in each frame he leaves the completed outlines behind him. He mimes holding the feather, swaying backward as he drags it in an arc along the wall. He holds a real crowbar to the drawing of a wine glass as it shatters. He may hold nothing at all while a spanner, the crossed wrench used for hubcaps, multiplies into an enormous spiral.

Is this street art, photography, drawing, or performance? Somehow his actions are the drawing, as it takes shape and transforms. At the same time, the act is itself a fiction. Obviously a crowbar is not shattering black chalk, and obviously the wheels of his bicycle are not leaving their curves in white chalk while he peddles away. If you had any doubt that he has staged each frame, look again at the bicycle. He has posed it lying on the ground, its wheels against a curved wall, while he shoots the scene from overhead.

Like any good illusionist, he achieves the impossible. The cyclist appears to be climbing an impossible arc against every known law of physics. Do not assume that he is quite so familiar as you may have thought either. This is not the barbed wire of commercial lots in New York City, and this is not the graffiti art of Barry McGee and SWOON—or its high-class appropriations by Jean-Michel Basquiat. Rhode's earlier performances all took place in galleries and museums, and his stop-action magic act appeared in "Street Level" (with Mark Bradford and William Cordova) at ICA Boston. He is not from the streets here either, although he once created a display for the BMW Art Car project in Grand Central Station.

Rhode is from South Africa, where he obtained a graduate degree before moving to Berlin. Maybe that allows his allusions to race and class to stay more than halfway relevant, rather than just a boast of street cred. In Johannesburg, that barbed wire has had serious political meaning. Maybe, too, its seriousness is what allows him to play, knowing that posing is not quite the same as posturing. When it comes down to it, he is a successful international artist, clowning with and barely touching on an often divided and dysfunctional nation. As a trickster, though, he is the real thing.

Mendi + Keith Obadike ran at the Studio Museum in Harlem through June 30, 2013, with the New Museum project in June 2012. Robin Rhode ran at Lehmann Maupin in Chelsea through February 23, 2013, and on the Lower East Side through March 9.