Shock Art Without the Shocks

John Haberin New York City

Robert Mapplethorpe: 50 Americans

Pluralism, Political Art, and Ken Johnson

"I, too, sing America." When Langston Hughes wrote that, he was not just protesting. His poem sings, and like Walt Whitman before him he sings of himself, "the darker brother." For all an African American's felt racism and exclusion, "Tomorrow, / I'll be at the table / When company comes."

Has his prediction come all too true? Racism is sure not going anywhere fast, not when the president must display his birth certificate, in the long form. Obama could be quoting Hughes: "I, too, am America." But what about art? Art accepts anyone, right?

In fact, it accepts almost anything—and that may present a problem. As Irving Sandler said on public radio, "We're in a situation of total pluralism," and it is not pretty. On that same panel, however, Ken Johnson disagreed. "Art can appear in almost any form," he complained, "but the orders of the art world are pretty tightly policed ideologically." For Johnson, art's acceptance of diversity is itself an orthodoxy. "You could say that it's a liberal festival."

As if to prove his point, a gallery claims Robert Mapplethorpe, who all but ignited the culture wars, for America. The Corcoran canceled a retrospective, which had opened in Philadelphia in 1988, and a museum director stood trial for pornography. Barely twenty years later, has the dark side of art lost its power to shock? Is anyone now welcome at the table, except those who would turn a black or gay male away? And is that a bad thing? In fact, the photographs still unsettle orthodoxies, Johnson's very much included.

Tea time in Chelsea

Johnson's host, Leonard Lopate, put the problem this way: "Now there was a time when artists could shock you." He was contrasting art now with the Brooklyn Museum in 2000, when Chris Ofili drew the wrath of New York's mayor. Now Marina Abramovic can stand naked in a museum, and no one blinks an eye. Actually, Abramovic wore a dress so long that it did not reveal so much as an ankle, while the Museum of Modern Art found younger men and women to recreate her performance upstairs. Still, Pipilotti Rist has poured her body out all over the atrium on video, and people brought their kids.

The point seems obvious. First Modernism broke pretty much every rule, and then Postmodernism challenged its exclusions, along with the myth of the avant-garde. Everyone still complains about the system, but artists like William Powhida or the Bruce High Quality Foundation get to turn their complaints into a show. Outsider art competes with mainstream art fairs, and women make up the majority of MoMA's survey of drawing. Jerry Saltz still slams the museum's gender imbalance, and Roberta Smith worries that galleries have chased out everything but big-money installations. Once New York's most influential critics are complaining, however, something must already have changed.

It may seem odd to wax nostalgic for censorship, but Lopate's panel does feel shortchanged. The avant-garde is dead, without an heir to take its place. As Johnson notes, anything goes in the movies, so how can art hope to stand out? Amei Wallach defends the vitality of political art, as with the recent video installation by Krzysztof Wodiczko about the Iraq war. Still, the others are not buying, and Johnson thinks that political art only makes things worse. For him, art no longer shocks because the shock troops have taken control.

Pluralism? "No," he insists, "the only thing that would be shocking in the art world is if a great Teabagger painter came along." Lopate chides him a bit. "You work for The New York Times, don't you?" Johnson, however, is not budging. Presumably that just goes to show the dominance of the liberal media.

Political art is pretty liberal, and institutional critique can look awfully institutional. Louise Lawler now blows up her photographs of museums to the scale of an altarpiece. For every boring lecture by Hans Haacke and Martha Rosler (despite her wonderful garage sale), however, art offers much more. In just one weekend in Chelsea, one could have the vivid personal experience of black America from Radcliffe Bailey, Thornton Dial, and Kara Walker. They follow the experience of New Orleans torn by race, crime, and natural disaster in Deborah Luster. Almost as recently the Whitney has protested torture with Jenny Holzer and Jill Magid, the toll on gay men with Charles LeDray and Paul Thek, the disaster of urban America with Sara VanDerBeek, and pretty much all the above with Glenn Ligon.

For me, Johnson's critique is frightening and wrong. Like the rest of the panel, it forgets the shocks all around him. Like them, too, it blurs the past role of an avant-garde. It overlooks the conflicts, drift, and conformity within pluralism. Most of all, it mirrors the lies of the right-wing extremists he misses so much. It turns upside down the real nature of power and ideology in America.

Balance in the art world

First, culture has a short attention span, and some critics have short memories. All that hassle over Ofili and the Young British Artists was ten years ago, and apparently ten years is an eternity. Never mind that YouTube censored a video by Amy Greenfield in 2010. Never mind the withdrawal of David Wojnarowicz from the Smithsonian just weeks before the panel. Never mind the Maine governor's removal of a pro-labor mural a few weeks later. Pluralism means the broadening of art's audience and art's growing acceptance of popular culture, but it is not pleasing everyone.

Second, art does not depend on shocks for its survival, although it can still surprise me. It does practically every day. Conversely, modern art long ago held more than shocks. Jackson Pollock earned public derision while posing for a magazine, and more power to him. People have lined up for Picasso and Matisse for a long time. With luck, one can cherish art after the avant-garde, just as one can revere the artists who came before it—although one can still pass judgments and hope for more.

Third, when it comes to shocks, the panel scrambled several kinds. An avant-garde is not the same as shock art, and shock art is not the same as political art. Luster can see New Orleans through the lens of older photography, while VanDerBeek can see both New Orleans and photography through abstraction. As the Guggenheim recently argued, Modernism encompassed Fascism along with protest. Much of it was apolitical rather than dogmatically liberal all along. Some of it, like Russian revolutionary art, disdained liberalism, too, but from the left.

Fourth, political art often fails, and that says something about the politics of art today. It is often anything but liberal—part of a scene in which museums court collectors, dealers become museum directors, and the only institution is money. Not that the market for art or imagery from consumer culture is necessarily a bad thing, but they are real all the same. That is why artists keep begging for alternative spaces amid the pluralism. It is also part of why so many artists are liberal. So are most people with advanced degrees, little money, and no outlet at The New York Times.

Johnson acts as if liberalism in the art world were a matter of brute force, institutional pressure, mind control, and ideological fervor. He might ask instead what it would take for the Tea Party to make great art. He might also ask about the contradiction between his complaint and his authority. He writes not just for the liberal media but for the paper of record, and he returned from a brief stint in Boston because it was not serious enough for him. He also wields authority in part because many share his quasi-religious belief in painting—especially painting just brushy enough to preserve an unbreachable ideal of self-expression.

I do not wish to overstate his position. Johnson loves and supports art, if not formalism or conceptual art, and everyone says silly things with the microphone on. Still, his comment cuts all too close to real-world politics. The plea for Teabaggers reflects an insider's ideal of "balance" in the media, a balance in which all statements are equally true. It propagates a lie—of the extreme right as oppressed and the transfer of wealth upward as courageous. It paints intellectuals as the true power elite, sipping their herbal tea.

Fifty-one Americans

Somehow, popular culture does remember. On the occasion of China's stifling of dissent now, Ai Weiwei tops a Time list of ten persecuted artists, but Robert Mapplethorpe still deserves ninth place. Not every artist could get a hundred congressmen to denounce him, as they did as his retrospective hit Cleveland—or even to know his name. But does all that seem like ancient history? When the photographer died of AIDS in 1989, the very year his retrospective died on its way to Washington, did art's shocks die with him? Not really, but something has changed, and that might not be such a bad thing.

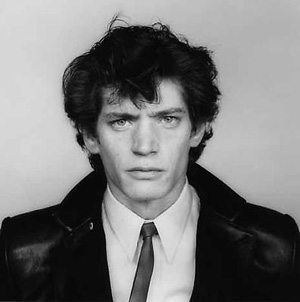

When Sean Kelly calls its latest Mapplethorpe show "50 Americans," one may do a double-take. Where are the Americans? Some heads are cut off, and some subjects, including flowers and landscapes, are not even people. The photographs provide a modest survey of the artist, including such themes as nudity, gay sex, and Patti Smith. They all have his mix of charisma, the dark sheen of human skin in black and white, perfection, and provocation. The most obvious symbol of America, the flag, is darkened and frayed at the edges.

When Sean Kelly calls its latest Mapplethorpe show "50 Americans," one may do a double-take. Where are the Americans? Some heads are cut off, and some subjects, including flowers and landscapes, are not even people. The photographs provide a modest survey of the artist, including such themes as nudity, gay sex, and Patti Smith. They all have his mix of charisma, the dark sheen of human skin in black and white, perfection, and provocation. The most obvious symbol of America, the flag, is darkened and frayed at the edges.

The exhibition title places him up there with Robert Franks in The Americans, Mark Steinmetz, and Lee Friedlander in "The American Monument" or "America by Car." He, too, sings of America. Not bad for a kid from Queens who hardly left New York and who first photographed Smith in the photo booths of Coney Island and, for Jared Bark, Times Square. Stranger still, no such book or series ever existed, until now. Those fifty Americans are not the subject of a road trip, but the curators. The gallery recruited them online, one from each state of the union, to choose a work apiece and to say why.

Some have entirely personal reasons. The torn flag reminds one man of the Vietnam War years, when he studied in safety. Another looks at flowers with the expertise of a gardener. Gays find strength in displays of male eroticism, like a cock paired with a gun. Most others pick women—especially Lisa Lyon, the body builder. An athlete sees in Lyon a celebration of her own womanhood.

Others take comfort in universal truths—or at least widely accepted ones. One swore not to select a portrait of Smith but could not help himself (but no, not the album cover), and Willem de Kooning appears along with William Burroughs. A calla lily with its penile center is "calming," says one, a frontal nude is simply well proportioned, and the tenderness of raw flesh is "timeless" and "natural." A figure wrapped in surgical gauze expresses the "need to escape" and to "break free." The dying artist's self-portrait in black, looking unflinchingly forward and with a death's head, has unsettled me as much as anything he did. Here it stands for the struggle of anyone "facing death."

Most of the fifty had not heard of him before, knew him as only a name, or were only vaguely aware of him, but they admire him all the same. And their vagueness of recollection attests to the increasing vagueness of the boundary between high and low culture. The gallery frames the show with two self-portraits, but one stands out front, while the other comes only next to last. This, they say, is no longer just him but something more. The culture wars have ended, art and Mapplethorpe have won, and everyone gets to take credit. The chickens have come home to roost, and Americans have opened a hatchery.

Democracy and desire

Suspicious? Those who deride art as a liberal love fest will relish a biracial embrace, especially one chosen by a Southerner. Those like me who distrust the uses of art, platitudes, and institutions will be warier still. Is this just another abuse of social media, trolling the Web and condescending to ordinary feelings? One guest curator marvels that Mapplethorpe sure knew a lot of celebrities, such as Susan Sarandon and Deborah Harry. A man treats a woman fondling her own tits as soft-core porn, and no one notices that Lyon violates gender norms.

Then again, if people find personal associations and timeless truths, they are saying that the art speaks to them. It acquires new meanings after the artist's death, which is what art is supposed to do. Smith calls her beautiful account of her early years Just Kids, because they were just kids, and it has become airport reading. Besides, many of the curatorial statements are quite sophisticated. Lyon, they say, pairs "excess" and "beauty." A woman's hair, including pubic hair, presents a "barrier," even as it engages the viewer with its erotic charge.

The show loads the dice, but so does anyone who touches it. The Guggenheim already rescued Mapplethorpe for "the classical tradition" in 2005. When Cindy Sherman curated "Robert Mapplethorpe: Eye to Eye" in 2003, she was coming out from behind the camera and exposing herself, just like these fifty Americans. Is the show of democracy real? If so, it is because of the interaction between people and art. Jesse Helms should have looked as carefully before denouncing this art.

Has the division between high and low altogether given way to porous boundaries and democracy? Not really, any more than the free market itself functions as an efficient response to human desire. Otherwise, every one of these guest curators would own a Mapplethorpe, and the recession would have ended. Money sets the terms for art, which now and again draws a crowd. Still, the crowd has voted, not so-called liberal institutions. Once again, an avant-garde does not require public failure, artistic shocks do not require political art, and political art does not require the culture wars.

A better critique of the art world has to recognize the mess. "50 Americans" is hardly critical, in either sense of the word, but it not a bad place to begin. On the one hand, Mapplethorpe is no longer just political art. It is art for fifty or more individuals. On the other hand, his entire body of work becomes political art, and political art survives as an expression of personal feelings. This may not shock, but its acceptance is long overdue.

Of course, change was under way in the artist's lifetime, which is what started the culture wars in the first place. His retrospective made it through two stops without getting anyone riled up, and people like Helms were using it as a club. They were like Johnson, demanding art for Teabaggers. Langston Hughes might be pleased: "Besides, / They'll see how beautiful I am / And be ashamed—" Now fifty Americans find beauty, and Johnson should be ashamed.

Leonard Lopate's NPR panel aired March 11, 2011, and "50 Americans" by Robert Mapplethorpe ran at Sean Kelly through June 18. The large work by Louise Lawler ran at Metro Pictures through June 11. A related review looks at Robert Mapplethorpe in retrospective.