Unabashed Women

John Haberin New York City

Born in Flames, Shigeko Kubota, and Huguette Caland

Some women refuse to shut up. To reach "Born in Flames" at the Bronx Museum, you must first pass a torrent of words. Text on a lobby wall reads like ecstatic poetry, with triple slashes in place of line breaks and a demand for, among other things, "the freedom to be unabashed."

The curator, Jasmine Wahi, sounds confident enough when she speaks of "what could have been, what is, and what is to come." (How many museums have a curator of social justice?) Like a womb-like structure on the way in, these artists are giving birth, as the exhibition's subtitle has it, to feminist futures. Be careful, though, for if this is about "futurity," its artists face a fearful, uncertain future. By its very definition, an ecstasy is out of anyone's control. That demand for freedom falls right in the middle of a passage that begins "in the belly of the beast" and could end anywhere in "this galaxy filled with dreams."

Not ready to give up on a woman's dreams? Shigeko Kubota put her body on the line fifty years ago now with Fluxus, while Huguette Caland contains multitudes, even when her art is clothing for one. A robe for Caland is filled with images of women, and she can imagine clothing many more. If, as tends to happen, the faces in a crowd blend together, do not hold that against her. Both celebrate the female body for its own sake. They find it everywhere, not least in video at MoMA and abstract art at the Drawing Center.

When the flames have died

Giving birth may not be easy. Wangechi Mutu, who has brought her women to the façade of the Met, sets that womb amid scraggly totems. Further inside, ceramic heads by Rose B. Simpson are trapped in rough cylinders, nails or spears, and their own harsh glares. Seated women for Huma Bhabha may have endured torture or the electric chair, leaving little more than plastic bags for lungs. Shoshanna Weinberger promises nourishment, but from a Grove of Invisible Fruit. Come to think of it, "in the belly of the beast" quotes Jack Henry Abbott, a killer who drew support from anything but a feminist, Norman Mailer.

"Born in Flames" takes its title from Lizzie Borden, who in turn takes her name from a notorious killer. Her 1983 film lends a touch of activism and optimism. Over the course of ninety minutes, women sing, protest, and simply engage in dialogue. The rest of the exhibition dates to just the last five years, if that. It also sticks to fourteen artists, almost all of color. Borden sticks out by making her focus class rather than race or gender.

The compact selection relieves the show of having to arrange artists by theme—or even to find one. After Mutu, it turns mostly to painting, works on paper, and video. Still, almost everyone has an eye to three dimensions. Caitlin Cherry paints cheery women in a heavy frame close to a stage set. Clarissa Tossin weaves acrylic strips into a jungle or sea of blue and green. More strips contain the molds of cell phones, plastic bottles, and DVDs as A New Grammar of Forms, if only a disposable one.

If anything unites them, it is that uncertain future. Yet even the scary stuff holds out hope. Tourmaline looks back to Seneca Village, a black community displaced for construction of Central Park and perilously close to the Met. In facing photos, women in white inhabit a tropical richness or ascend into clouds. Sin Wai Kin (Victoria Sin, reclaiming her birth name) interrupts herself on video, to bring a sense of humor and a relief from the news. Dressed as a TV anchor with a puppy face and posed in front of fiery suns, she announces today's top stories without delivering a single one, because "that's it" and "that's not."

The ambivalence of hope and fear is plainer still in painting. Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum depicts a World War I soldier standing guard, but also women holding their own, and her charging horses could go with either one. Firelei Báez paints shimmering purple bodies amid flowers because, a subtitle has it, we love you. They may have found peace or death. The fashion for comic-strip art is upbeat all by itself, and Chitra Ganesh populates hers with female warriors and a mystic passage. Still, their text has it, When a Girl Is Terrified She Might Run for Her Life.

Could hope win out, and could that be enough for a feminist future? Saya Woolfalk covers partitions with mystic symbols, although her title speaks of uninhabitable lands. In one last sculpture, by María Berrio, a girl lies on her back amid what might be birds of prey looking to feast on the dead. Then again, they could be swans nurturing a thing of beauty. She may have been born in flames, but bronze lasts. With luck, she will never enter the belly of the beast.

Coming down to it

One day, that nude will finally descend the staircase. Maybe not in time for Marcel Duchamp, who harnessed the energy of modern art and the machine age in paint, as Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) in 1912. Maybe soon, though, for Shigeko Kubota, who borrowed Duchamp's title for a 1976 video. And she should know, for the on-screen nude was her. It came halfway through a decade that established her as a leading figure in Fluxus and a pioneer of video art. Just seven works show how she did it, as "Liquid Reality" at MoMA.

Fluxus, a movement that emerged in the 1950s (brought alive in photography by Jimmy DeSana), could claim an ancestor in Marcel Duchamp, for his anti-art, appropriations, and tongue-in-cheek titles. It could only envy the shock he made when the painting returned for the 1913 Armory Show in New York. Still, Duchamp was enough of an artist to have picked up on how Cubism and Futurism captured motion as stasis and a moment in time as art. Kubota is in more of hurry. Each of four plywood steps has a monitor, and she appears simultaneously on each one, amid a sea of pixels. A swirl of white surrounds her naked body with, she liked to think, the "energy of electrons."

Like Nam June Paik, a partner in Fluxus and for a while in life, she reveled in test patterns and digital static. Like Paik, too, she treats video as sculpture. She loved Sony Portapak cameras for their portability, but also for their weight. She brought out the weight in a portable TV as well, using one as a pendulum for Video Haiku—and binding another with twine to a slab of pink quartz bearing the names of her ancestors, for her Berlin Diary. She remade the old-fashioned "TV box" in her art as well, in plywood, sheet metal, plastic, and mirrors. She was translating Duchamp's painting into video, while treating technology as her paintbrush.

She was putting herself on the line, too, starting with the shifting artificial colors of her Self-Portrait, around 1970. Ever wish that Paik's partner in art, Charlotte Moorman, could have been a creator as well as cellist and performer? Like Brenda Goodman, Kubota made her own art about a woman's body even apart from video, when she dripped paint from her vagina. It appeared again in a 2008 show of "Art and the Feminist Revolution, and it left the men in Fluxus uneasy—much as did Yoko Ono and Carolee Schneemann. Still, she stressed, she made her impact through art alone. Her drips and random patterns cut Jackson Pollock and John Cage down to size, but Pollock and Cage set her free.

She shares the video stage with nature. Yet it is a nature of technology's making and unmaking. Mountain landscapes peek out from small monitors, as Three Mountains, but in three plywood pyramids. Oceans and grass serve as visual accents in her Niagara Falls, with rushing water her audio accents. Three monitors project downward, onto a metal tub, as River, and the face in the river once again is hers. For Kubota, water and test patterns alike are cleansing.

They are also shattering. She and nature become visible only in fragments or reflections, like memory itself. One pyramid is open on top, but too tall and too wide for one to look down on the monitor within. The show occupies MoMA's Studio, two rooms within its permanent collection of postwar art, not far from more early performance video by Joan Jonas. It can seem like a mere footnote to the collection at that, filled with nostalgia for old TVs. Still, it makes clear how much today's video art has its ancestors. If hers lie in quartz and in pixels, right up to her death in 2015, it is not too late to reclaim their descent.

Clothing the masses

Huguette Caland was thirty-nine when she lit out for Paris, children in tow. She had shown a facility in ink back in Beirut, with off-kilter patterns that, given half a chance, just might settle into a woman's legs. It was time that she showed what she could do as an artist and who she could be, and marriage was holding her back. And Paris was ready for her.  Starting in 1973, she drew praise for oil on paper that translates her fields of white into nuanced color, as Bribes de Corps (or "body parts"). Their clean curves, with hints of flesh, showed that Minimalism could be gendered, much as in art today.

Starting in 1973, she drew praise for oil on paper that translates her fields of white into nuanced color, as Bribes de Corps (or "body parts"). Their clean curves, with hints of flesh, showed that Minimalism could be gendered, much as in art today.

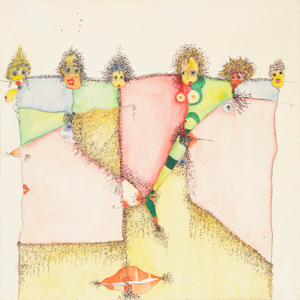

Looking back, the early patterns in ink might suggest stockings. Then, too, they might simply be drawing. It was only natural, then, to seek a more lasting outlet by combining her loves—not on canvas, but in fabric. She began to design caftans, or full-length robes, with their white a field for play. Sure enough, women crowd between the legs of one, while others have room for breasts, lips, and eyes. The Center has just four out of a hundred (including collaborations with Pierre Cardin), but they easily take over the show and the gift shop.

Had Caland left Lebanon behind? She had many allegiances, just as caftans can pun on academic gowns and Palestinian tapestry. Her father was her country's first prime minister after colonial rule, but she married a Frenchman. She had a brother in Turkey and found parallels to her drawing in Byzantine art as well. She moved once again, this time to LA, where she found herself at home among such abstract artists as Ed Moses and Larry Bell. She bought a lot in nearby Venice from Sam Francis, who treats stained, unstretched canvas almost like her fabric.

She had multiple allegiances, too, when it came to herself and men. She stayed on good terms with her husband and abandoned her California dream in 2013 to bring him solace in his last years. She remained in Beirut until her own death in 2019. She had taken care of her father long before, and his death freed her for that first move to Paris. Was she escaping not just one but two family ties? No doubt, but she might have heard his voice in her head calling her to be true to herself.

To her, that meant leaving a woman's traces in art. Bribes de Corps means body parts less in the sense of arms and legs than scraps or fragments. And men, she knew, have a way of reducing women to their parts. Still, she delighted in the bits and pieces for their sensuality, as with Big Kiss in 1978, and never lost her sense of humor. A row of small faces presides over Homage to Pubic Hair in 1992, with wiry hair themselves. (Caland herself had fairly straight hair and had put on weight.) She made friends in LA, too, with Chris Burden, who dragged his body across broken glass and through hell for his art.

The show's title, "Tête-à-Tête," promises intimacy as well as, taken literally, body parts. Bits and pieces can be arbitrary, though, and so all too often are her busy, shifting designs. Clay figurines from 1983 are suggestive, but not much more. Still, she found new energy with a new century in larger works and in color, holding together her scrappy line. Best of all, she let ink spread into stacked horizontal stripes reminiscent of Agnes Martin but thicker and messier. And the darkest and messiest barely disguise a mysterious woman.

"Born in Flames" ran at the Bronx Museum through September 12, 2021, Huguette Caland at the Drawing Center through September 19. Shigeko Kubota ran at The Museum of Modern Art through January 1, 2022.