Pathways to the Sky

John Haberin New York City

Yoko Ono

Blame it all on John Lennon. For a moment, I wanted to do just that. Yoko Ono has earned her share of love, scorn, and hatred, but almost anyone will leave her work from the 1960s walking at least a little lighter. You might even find yourself asking just who messed up whom.

You will definitely find yourself grateful to be back on solid earth. Ono makes one grateful for small things and passing things, just as she also has one reaching for the sky. The layout at the Modern revolves around a room devoted to unsettling both the ground and the sky. It has her Sky Machine, its first instance from 1961, a stainless steel vending machine that dispenses her handwritten card designating the sky. It has her 1966 Sky TV, airing a little bit of nothing, and a small speaker in the wall releasing bird sounds. It centers, though, on a spiral pathway to the sky.

An ordinary spiral staircase, it gives access to a skylight that few visitors will know was there. At least it does in principle, since it has room for only one person at a time. The patient or lucky ones will have access to an aspect of the sixth-floor galleries that curators generally do their best to hide, airier and more open to natural light. They will also get an unusual view of midtown architecture, top floors only. As one ascends, though, the metal stairs become more and more unstable, until one's stomach shakes along with them. If only one could descend without them, but then if only one could fly.

Before the buzz

Ono's best work is like that—collaborative and site-specific, conceptual and intensely physical, close to poetry and downright funny. Her worst is self-involved, silly, and serious to the point of pretension. The tricky part is that two sides are inseparable. One just has to go along for the ride. Like the staircase, the show immerses one in a museum experience that MoMA's 2004 architect was too shortsighted to imagine. It also immerses one in art back then as spare as Minimalism and as culturally aware as Pop Art, but more feverish than either one.

People of a certain age will know Ono mostly for her part in breaking up the Beatles. How large or small a part, I leave to you. They will picture her sitting sullenly in the studio at Lennon's insistence, in her customary black, as if the band had made every day "take your significant other to work day." They may remember her pretentious side, too—the primal scream, the couple's "bed-in" for peace, their pose with Lennon in fetal position for Annie Leibovitz and the cover of Rolling Stone, and a poster's insipid promise: War Is Over (If You Want It). Lennon's "Ballad of John and Yoko" plays the victim card just as gratingly, with how "they're going to crucify me."

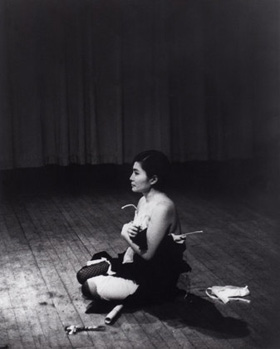

People more familiar with art will know her from Fluxus (brought alive in photography by Jimmy DeSana), the "anti-art" movement founded by George Maciunas with an assist from Shigeko Kubota. He enabled Ono's first New York solo show, in July 1961 on the Upper East Side. They will also know her largely from one work, Cut Piece, which gets pride of place in the exhibition's central corridor with the assist of a 1965 documentary short by Albert and David Maysles. Ono sits motionless and impassive for nearly ten minutes, in a button-down top and fishnet stockings, as a visitor snips her naked. She does nothing and he does everything, but then he cannot change anything but her clothing. She asserts a woman's body, her creativity, her vulnerability, and her sheer existence, while barely masking her fears.

The curators, Christophe Cherix and Klaus Biesenbach with Francesca Wilmott, give her and Lennon together their own room at the show's end, the one room with a closed door. It is also the one loud room, even with headphones for tracks by the Plastic Ono Band. A fly nestling on her nipples on film makes quite a buzz. Emily Dickinson could easily have heard it when she died. By setting that room apart, MoMA says that there is much more to Ono than this. It makes a case for her at the center of the early 1960s in New York.

The case starts quietly, with very little buzz. One can strain to hear Ono coughing or watch her Lighting Piece, in which she strikes a match and then lets it burn out. From there, one can turn to one's left to see her eye strain to stay open, in Eyeblink from 1966. She is both exposing herself and hiding, and so can exhibition visitors—in a large black bag, a recreation of her 1965 Bag Piece. In one early performance, two actors stripped naked and clothed themselves again, with nothing to show for it but the awkward dance of the bag. It approaches abstraction, in gelatin silver prints of its dark outlines and reflected light.

Alternatively, one can turn to one's right, for documentation of her studio on Chambers Street in Lower Manhattan in 1961—well before it became tourist access to One World Trade Center, Ground Zero, and the wealth of Tribeca. Maybe Ono's impassive gaze was only a cover for her shyness all along, but she sure attracted company. With La Monte Young, the composer, she arranged a program in music, installation art, and performance. The audience ran to as many as two hundred, including John Cage, Marcel Duchamp, Isamu Noguchi, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Peggy Guggenheim, and Maciunas. Not exactly flies on the wall. They also suggest a context for her work.

Conceptual art for the senses

Like them, it is intelligent and interdisciplinary. Born in Japan in 1933 to a Buddhist mother and Christian father, Ono moved with her family after the war to suburban New York and studied at Sarah Lawrence. She drew on both cultures, much like MoMA's earlier exhibition of avant-garde Tokyo. She bows to tradition and defaces it when she smears Sumi ink over western and Japanese letters. She titled a series Grapefruit because a grapefruit is a hybrid of other citrus fruit, brought to America in 1853. She took both cultures with her, too, when she traveled to Tokyo's Sogetsu Arts Center in 1962, for her first major public performance.

Her early work is and is not just conceptual art. Like Lighting Piece, it can consist entirely of typed instructions or their instantiation. Either way, it is both ephemeral and altogether real, like a woman in a bag or a smear of ink. Her burning holes in canvas could leave rough, dark abstractions or nothing at all. Stepping on the irregular outlines of her Piece to Be Stepped On is both daunting and strangely comforting, and so is a room for people to touch one another. Ono makes art from words, but her words engage all five senses, from visual art and music to touch, taste, and smell.

They also engage the art of her time at its most memorable and wildest. When Ono manipulates the picture tube for Sky TV, she follows Nam June Paik. When she looks through a telephone book or seeks a meeting point between East and West, she parallels Om Kawara, and a drier version of conceptual art was developing in LA with John Baldessari. When she creates white chess sets, she pays tribute to art's leading chess master, Duchamp—and of course her vulnerability in performance looks ahead to Chris Burden and, less happily, Marina Abramovic. Cage, though, looms greatest, enough that a work refers to him simply as J.C., like the Messiah. He introduced the rhythms of chance and silence, and artists like Ono or Robert Smithson eagerly picked them up.

Ono takes all of this seriously, except when she does not. One can hear the poetry and the laughter in Painting Until It Becomes Marble, Painting for the Wind, or Painting to See in the Dark. They have their most extended run, though, in Grapefruit. A fat artist's book, it has instructions to send a smell to the moon and to count the number of stars in the sky. It commands people to count the wrinkles on each other's stomach. You get to decide which is silly, which is sly, and which is beautiful, and you get to change your mind.

The show could easily have ended there, and so could a full retrospective. Ono produced less and less after her move from New York to London in 1966—and less still after 1971. Even the one new work, the spiral staircase, extends a pair of ladders that Lennon admired in 1966, as well as a stepladder leading up to the word Fly. Grapefruit also poses most clearly the puzzle of what to call her art. One could think of one hundred fifty-one typed instructions as art never to be made, as the work itself, or as hypothetical works of art. One can think of performances based on those instructions as original works or copies.

Arthur C. Danto posed much the same questions in trying to locate the difference after Andy Warhol between art and "ordinary things." Are any two of Ono's Smoke Paintings what the philosopher called "indiscernibles," and if so why should one care about either one? What happens to the "originality of the avant-garde"? Then again, maybe those works are not so indiscernible after all. Maybe just reading her instructions a second time opens fresh channels for the imagination. Her words, performances, and objects may pass, but they can still linger in the senses and the mind.

Up the down escalator

One can see what attracted Lennon (and, just to be clear, he has been a lifelong hero of mine). Ono's first London show recapped her career to date, and he was the first to sign the guest book. He must have taken a hammer to her Painting to Hammer a Nail as well. One can see what attracted her, too. He had, after all, sought her out, where Mick Jagger would surely have preferred a more polished and prominent performer. When she exhibited a room with its furnishings cut in half a year later, Lennon told her to bottle the other half—and a shelf of bottles became their first collaboration.

Her reply invoked Plato's parable of male and female: "we are already half." Who is to blame for what happened next? Maybe no one. The idealism of a past generation always looks a little foolish, and anyway Lennon was wry enough not to buy into anyone's ideals, except maybe his own. Their bed-in at the Amsterdam Hilton sure looks self-aggrandizing, but it confronts the reality that a Beatle had no privacy, not even on his honeymoon.

If the show peters out after 1966, Ono was losing momentum on her own as well. Work was becoming less ephemeral and less personal, like silver spoons or a green apple on a pedestal, well before her encounter with Apple Records. The show ends in 1971 because Ono gave herself a MoMA retrospective that very year, without the museum's asking her in. Hopeful visitors found only a fiction. The artist, she claimed, had released flies inside. She was assaulting the very idea of a museum institution, even as she invited others to catch the buzz.

The actual retrospective is a second chance for the museum, a mere forty-four years late. The curators may hope that it will be redemptive for them, too. After a show of Björk, the latest in any number of disasters, critics have called for Biesenbach to step down. Now he gets a chance for a better outcome with another pop star, and he succeeds, up to a point—not because its subject was central to her time, but because she aimed for the fringe, as Biesenbach and Björk never could. Does the show devolve into documentation? Not too often, and anyway conceptual art is like that.

Can MoMA redeem Ono as well? It sticks to her work before age forty, after which she produced so little of value. In today's climate for art, one could dismiss it as yet another midcareer retrospective, anointing the next celebrity artist. And she is always at its center, from the earliest work, a book interleaved with human hair, to the flies on her breasts. Still, Ono's actual midcareer retrospective was a fiction, while her celebrity was not. And she created lasting but also open and collaborative art, for all the museum's insistence on the title "One-Woman Show."

As I tried to leave, to my annoyance, both escalators seemed to be running up. MoMA often diverts traffic to keep people in its grip. But no, a little girl was running up one escalator against its motion. She also came close to falling, so that a bystander had to rescue her. She was adventurous, comical, vulnerable, and foolish, just like the artist. Ono, though, has one landing on one's feet after climbing to the sky.

"Yoko Ono: One-Woman Show" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through September 7, 2015. Related reviews take up Yoko Ono at Asia Society some years before and in the galleries. A related review takes up Yoko Ono in the galleries later that year, with "The Riverbed."