Two Types of Ambiguity

John Haberin New York City

The eye, whose function we so certainly know by experience, has, down to my own time, been defined by an infinite number of authors as one thing; but I find, by experience, that it is quite another.

— Leonardo da Vinci

Barbara E. Savedoff: Transforming Images

Sylvia Mendel

A photograph is a trace. Light—along with good helping of chemistry, electronics, and other human interventions—deposits an image, and one interprets it as the image of something rather than of light. In plain English, it looks real.

According to Barbara E. Savedoff, that interpretation hinges on a kind of trust, a privilege accorded uniquely to photography. And, she observes, a privilege can always be revoked.

The copy and the trace

For now, people believe what they see, even when it makes them despair for what they know. Think of Abu Ghraib. Think of the administration's efforts to hide from the public the wounded, the dead, and even the coffins from Iraq.

However, as digital manipulation grows as routine as a false campaign ad, habits of belief may change. In Transforming Images: How Photography Complicates the Picture, Savedoff explores what those habits mean for the experience of art.

And then there is another kind of trace. A mask hung over the bar one April evening. The artist, Sylvia Mendel, had cast the face directly from the young, relaxed, and largely indifferent woman who was serving me. The face suffered little or no manipulation, digital or otherwise. Yet she looked no less unreal for that.

In its mirrored niche, flooded with light from above, the mask's whiteness seemed still stranger and more inhuman. Its smooth surface made it all the more ghostly. Every imperfection in the plaster stood at once for deformation and for evidence of the sculptor's hand.

Plato denigrated art as a copy of appearances, themselves copies of reality. In their different ways, photographs and masks promise representation without the need for copying. Savedoff uses that model to develop a fascinating natural history of ambiguity in art. But is that enough?

Can esthetics pursue the role of the imagination without longing for a less ghostly reality that may never exist? I shall consider both photography's claim to truth and the art of Sylvia Mendel.

Habits of belief

Begin with that mask. Set aside the association of masks with a medieval carnival, as with James Ensor. Someone, somewhere, had imagined the face of absence, destruction, and decay. What else could live so comfortably amid half-empty bottles of alcohol?

The waitress, for one, who had served as the model. I had no idea. I had seen no more connection to life than the sculptor's art. Even once I knew, I could barely see the resemblance. The mask captured a literal trace, and yet no one would call it realistic or even ambiguous. It had its own presence, but not the presence of a sensual, living being. Could photography truly claim something more?

The camera, people say, does not lie, but art has a way of speaking rather gnomic truths. Even one of its most traditional aims, representation, hinges on the ambiguity between the two-dimensional image and the illusion of three dimensions. In a wonderful first chapter, Savedoff supplies a history of this ambiguity in painting. It can heighten one's sense of the marvelous, as in trompe l'oeil. It can underscore the multiple levels of reality in myth and religion, as in the grisaille scenes on the exterior of an altarpiece or the animated statues in a Dutch church interior. When household objects bleed into each other—or into represented works of art, as in Paul Cézanne and his Still Life with Plaster Cast or Cézanne's Card Players—it can call attention instead to the artifice and its limits.

With photography, she argues, something changes. One understands a painting as the creation of human being, but photographic illusion defies and survives mere human intervention. Rather, one accepts a photograph as a trace of real, although a photographic negative, as in the work of Vera Lutter, can look quite ghostly. When the mirror in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère makes no sense, one takes added pleasure in the work, and one credits Edouard Manet for his deconstruction of realism, gender, and café society. With a photograph, however, one takes ambiguity as a betrayal—sometimes with gut-wrenching results.

When Henri Cartier-Bresson captures The Decisive Moment, a man leaping over a puddle, one cannot get over the elation that he is suspended in midair. When Walker Evans documents torn billboards, one mistakes the paper for a human face and the tearing for an act of mutilation. No matter how great the ambiguity, one cannot shake—or help be shaken by—the illusion.

Those habits of belief, she continues, extend to film. They explain the poignancy and wit of a movie within a movie, as in the creative twists of Buster Keaton's Sherlock Jr. I delighted in another figure suspended above the ground, in Spiderman II, just the other day. Finally, as a kind of afterword, Savedoff raises the question of how long, in a digital age, they can last.

Supplementing painting

Savedoff's account spans three media, seven centuries, and art's multiplicity of aims and effects to encompass ambiguity. Surely it takes that much, and she is up to the task. Surely, too, it takes unusual modesty for a scholar to treat a prediction for the future as an open question, not just a rhetorical one. Transforming Images, which I stumbled on entirely by accident, has all of that, and it merits far more attention than it has received.

Savedoff packs it all into a short book, with perceptive descriptions and relaxed prose. Ambiguity, she shows, need not preclude clarity. The examples, from grisaille to Keaton, had a way of anticipating my own thoughts.

No doubt that reflects shared roots. As a disclaimer, I should say that the writer studied philosophy and painting at Princeton, where I pretty much knew and understood nothing about either. Although we have lost touch, she has had many of the same close friends and influences as my own. Her work as a philosopher also reminds me of my own critical limitations as an amateur in breadth and rigor.

However, ambiguity turns on omissions and supplements. It stems from connections left unspoken—or inserted where one least expects it. A book on ambiguity, too, begs for attention to what it leaves out and where it exceeds its own arguments.

For starters, Savedoff's examples, like that great Cézanne in London, stick to Modernism's canon. She leaps from older art to a digital future, with little hint of postmodern appropriations that have done so much to question the naturalness of photography. Perhaps not coincidentally, the 1990s also marked the entrance of photography into mainstream galleries, a decisive shift from museum wings devoted to the medium—as at the reopened Museum of Modern Art still. The book can safely oppose painting and photography while treating the latter as a fine art, but in doing so it reflects specific museum practices.

That omission leads to the book's first act of addition. It comes in the preface, itself a site of supplementation. Savedoff asks, almost apologetically, why photography requires separate treatment. And in fact Chapter 1, on painting, stands as a self-contained survey of ambiguity. Photography supplements painting, and in the act it puts painting's claim to truth—or perhaps even ambiguity—in question. Interestingly, that story, too, parallels a tradition within Modernism, a common account linking the evolution of abstraction to the sudden irrelevance of representation after photography.

Your own eyes

The book's assertion of belief also has a notable omission—a belief in exactly what? It cannot mean belief in the represented objects. The power of Walker Evans and his signs, the argument insists, arises from a mistake. It requires a momentary, even lasting, belief in what one does not see. Besides, truth does not ensure understanding. One can recognize that acts of torture took place in Abu Ghraib without gaining the least insight into their culpability, causes, or extent.

Conversely, it cannot mean belief in appearances, just as a mask hardly ensures resemblance. As Savedoff notes, one does not take a blurred photograph to prove that people look blurry. As Chico Marx once said, "Who you gonna believe, me or your own eyes?" Like too many Americans at the polls after the invasion in Iraq, people prefer to trust in what they want—and what they want to know.

Already, ambiguity sits uneasily with a defense of naturalism. And the problem here raises a second act of supplementation. Certainty enters in context of an exploration of ambiguity and uncertainty. A book about transformation centers on a proposed point of stability.

Finally, Savedoff is wary of addressing why people believe. The book, not me, introduces the truth of photography through a parallel to masks. However, it then draws back from a reliance on a print's supposed origins. It acknowledges Joel Snyder's 1976 assault on all that. As Snyder put it in a 1983 essay, "What happens by itself in photography?" Given the myriad manipulations of an image, not much.

Faced with this, Savedoff falls back on the mere fact of belief. Fair enough, one might say. This is esthetics, not sociology. And, once again, beliefs carry weight, regardless of their validity.

Still, one sees again how closely belief and disbelief intertwine in Savedoff's enumeration of artistic stratagems. Evans and others, she explains, heighten illusion in much the same ways that painters have created ambiguity, through black-and-white images and two-dimensional subjects.

Desiring transformation

Savedoff's handling of the why leaves a puzzle. Here again omission entails supplementation—this time a twofold addition. Two theories sit uneasily together, and an afterword risks erasing the story at hand. If belief in photography arises from beliefs about photography, about how it works, why should it take the computer to change habits? Conversely, if belief stands on its own, why should digital manipulation matter? In either case, why do people believe what they believe?

Most people probably know little about photography. They have little understanding of how a camera works. They know even less of the chemistry behind a darkroom. They get used to an assault of images, in magazines and on TV, and they choose at times to accept. The digital camera may even end up deepening the habits. It puts everyone's baby pictures instantly online, just as Kodak once made photography affordable for everyone.

Conversely, people know a great deal about the movies. They know film involves actors, stage sets, editing, special effects, impossible events, and vast expense. They believe anyhow, at least for two hours. When I rented Before Sunset last week, the DVD special features threw me almost as much as Evans's advertisements. I had just been watching that couple, lost in each other's thoughts, and here they were in that same intimate, Paris street surrounded by cameras and cranes.

"I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking." Christopher Ishwerwood is submitting himself to the passing scene while staking his claim to authority. He is making the most memorable case for photography while working in words—and beginning with the word I. Perhaps also relevant, he is the gendered, homosexual subject, writing in the active voice and the first person while portraying himself as open and passive.

There is just no getting around it: representation admits ambiguity and belief, because even the most innocent eye is interpreting what it sees in light of understanding. Moreover, it seeks understanding in context of desire. As with the lasting strangeness of Diane Arbus, one cannot disentangle the urge to believe from the compulsion to look. When artists dare one to distinguish between still life as installation and science experiment, they seek amazement.

I could almost understand why it matters that digital art can lie and, paradoxically, why geeks obsessed with the "virtual" in virtual reality still believe in their art as a processing of raw data. I can understand why people learned of the Photoshop trick that placed John Kerry next to Jane Fonda and still came away distrusting his sincerity and patriotism. No one can detach truth and the natural from understanding and desire. Belief does not just depend on certainty. Belief also restores it, like a kind of magic—or a mask.

Dearly departed

People have cherished funerary masks, as the permanent trace of someone departed. For every memory, every bit of love and affection they preserve, they also testify to an absence. No wonder the custom feels so hard to contemplate today. In still other cultures, they have stood for spirits that can never quite assume human form.

Masks have another use, of course, one just as spooky. They hide. To mask something is to disguise it. No wonder it comes as such a shock to encounter Three Musicians, to discover that Pablo Picasso has placed nothing at all behind the masks. He takes visual art, like music, into the realm of what one cannot see.

When kids wear masks on Halloween, they delight in both aspects of invisibility, in disguise and in the inhuman. These days, with costumes generated by mass culture and mass production, the disguises may come more out of comic books and their film adaptation rather than the traditional stock of ghosts and witches. The game with masks has cheapened, perhaps, but it has not lost its nature. It has merely a redoubled distance from reality. And here too that distance preserves desires rooted firmly in the present—for candy and, too, an evening of a grownup's independence and authority.

People hold onto traces of the past with artistic, created images, too, as in a portrait gallery. Or they may look to signs even further from resemblance, like words. They wander in cemeteries to find famous names. They take actual traces from the headstones. Philip Larkin remembers a maiden name, "a phrase applicable to no one," as "what we feel about you then: how beautiful you were, and near, and young." In facing up to the terror one feels before Evans's billboards, one should remember that they are images not only of faces but also of signs—signs unmoored from their meaning by the camera, by actual human violence, and by time.

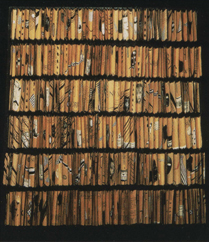

Like her masks, Mendel's other work turns words and other signs into images. She folds sheet music and magazine covers into boxes, in the shape of fireworks or undisturbed archives, the traces brown and mostly hidden. For materials, she scours everything from the streets of New York to back issues of The New Yorker, as well as what I imagine must be a very cluttered apartment. Some might say that she takes the rag ends of everyday life and brings to them fine art materials and an instinctive sense of beauty. She might prefer to think that she cherishes the sense of craft and style in anything from the bottom of a brown paper bag to modern art but crushes it, just enough to disturb the work and the viewer.

It has much in common with the first generation of Surrealism, which has itself inspired recent photography—the patchwork of a Paul Klee abstraction, Kurt Schwitter's reading lists, or Meret Oppenheim's sensual warnings not to touch. Up close, however, it may come closer to contemporary urban realism. The artist, who continued working as a therapist after 9/11, clearly knows something about trauma. Art like this finds traces everywhere, and much of it looks as if it might crumple up and vanish before one's eyes.

Who was that masked man?

Photography has a close but problematic relationship with those other kinds of traces, in art and in words. It left the closed community of galleries and collections devoted solely to photography just when postmodernists treated it and images alike as products of the mass market. It appears in newspapers alongside type, as one more sort of documentation. It can bring disaster home or numb one by repetition. Should one wonder that it has authority?

Either way, however, it thrives on recording what has changed—and that it has changed. Jason Shulman silvers over his photoengravings of the dead, so that it takes the viewer's breath to efface the present reflection and recover the past. People stop in front of tourist attractions to photograph each other. They do not need to prove that they exist, but they must prove even to themselves that they were there. Apparently, absence does make the heart grow fonder, even of oneself. As Jacques Derrida puts it more obliquely, "traces thus produce the space of their inscription only by acceding to the period of their erasure."

At its origins, photography seemed as much like magic as like an art or science, just as masks long had in the art of Africa—or art about Africa. People marveled to see the likeness, and they may well have understood how the new technology worked barely more than users of a digital camera do today. Those first daguerreotypes still amaze one with their ghostly sheen and their recovery of famous men and women from the past. Even now, photography can have a gentler form of that magic. When I see Robert Doisneau's Parisian lovers kissing out of doors, the black-and-white tones work not by heightening either illusion or ambiguity, but by standing for a nostalgic past, born of Europe and the movies.

Painting once had a similar power, or at least philosophers as dedicated to "the truth" in art as Heidegger thought so, it should come as no surprise that the digital age is also said to dispel its aura. It could represent divinity in human form. Over and over one reads accounts of a painter's superhuman ability to fool the eye, to represent something more palpably than it could itself. The dream of a higher reality is inseparable from the contrary dream of dispelling illusion, as in my epigraph from Leonardo. It has survived many changing definitions of the real in art, right down through abstraction, as for Georgia O'Keeffe and O'Keeffe drawings.

Savedoff has the insight to link ambiguity, illusion, representation, and belief. She is right to single out the role of photography in documenting and authenticating the visible. She is also right to see expectations as subject to change. Even in the four years since the publication, some things sound quaint. Who would explain a pixel so patiently today?

Despite herself, however, she falls into deceptively firm distinctions because, despite her own theme, she cannot describe transformation without a center of change. Criticism's seven types of ambiguity have become two, because one, photography's, commands the inside—at least for now. Yet neither photography nor painting seem likely to abandon their traces any time soon. And neither is likely to survive Postmodernism without a heightened suspicion of their presences in art.

Barbara E. Savedoff's Transforming Images: How Photography Complicates the Picture was published in 2000 by Cornell University Press, but I read it in December 2004. Sylvia Mendel exhibited at Caliban in April 2004, and a retrospective of Robert Doisneau ran at Bruce Silverstein through February 12, 2005. I first encountered Jason Shulman in "Still Life and Stilled Lives," at Ariel Meyerowitz through March 12, 2005. A related article looks at "Walker Evans: American Photographs."