What Was Realism?

John Haberin New York City

The Landscape of Modern American Art

An Art-at-Lunch talk at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. See the accompanying slide show for more! (But warning: it takes Flash.)

Abstract. When we think of realism, we may imagine a timeless truth—an artist's fidelity to nature and to what we see. We may imagine a time—in France, the period in art called Realism, before the Impressionists; in America, a time of growth culminating in the urban realism before World War II. Or we may imagine a style that can still be learned in school—an alternative to abstraction or Postmodernism.

In fact, realism in art has meant many things. And one way to chart its shifting meaning is to put aside for a moment the obvious—skills in light, color, anatomy, and perspective. Instead, we can ask how artists have represented not just the world but us—who we are and, even more, where we are. We can ask how that construction of ourselves changed, how it became so difficult, and what that means for looking at American realism today.

|

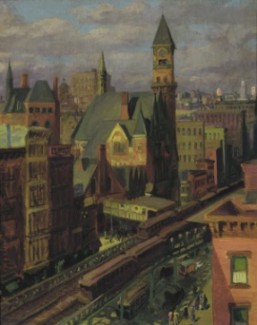

John Sloan, Jefferson Market |

You made a mistake!

Thank you so much for coming. Here, before Labor Day, I know you could be out there enjoying the real America, instead of hearing me tell you about it in pictures. And I'm honored to kick off this fall's series with you. In fact, when the Academy invited me to speak on American Realism and Impressionism, I was sure they'd made a mistake.

I'm a New Yorker, for one thing. I'm a writer, more used to my computer monitor than to a friendlier audience. But more, here I am, lecturing to an institution that, through thick and thin, has long upheld a tradition of American realism—and I am an outsider to that ideal.

I should explain that I was turned onto the study of art by two things. One was a book on early Northern Renaissance painting. The other was a college friend, back when painting meant geometric abstraction and the only Ashcan school was a mound of dirt on a gallery floor, maybe with some mirrors and torn rubber thrown in for good measure. From the standpoint of the first, American realism can look like a sad decline. For the latter, it seems at best a misplaced form of nostalgia.

I have written skeptically about historical revisionism that embraces so-called academic art. I have even made fun of Andrew Wyeth. I should probably be wearing a bulletproof vest, quite aside from my passing the Republican Convention to get to Penn Station this morning.

All this has an advantage, however. As something of an outsider, I can ask the obvious questions that another might not. Is American realism really alive today, for instance? And what is it—or was it—in the first place? Hence the title of my talk: what was realism?

Well, it depends who you ask. I don't mean a postmodern critique in which every reality is a construct, in what an exhibition on color, art, and optics calls "the mind's eye." It's probably true, but that's another lecture altogether: don't even go there. I mean that realism in art means—and has long meant—many things. For starters, consider what it probably means to all of us on a gut level, even people as knowledgeable about art as yourselves.

Alternate realities

As the saying goes, we know it when we see it. This, for example, is definitely realistic. Okay, sorry: that was from the French Salon, so here is American realism, one from Bo Bartlett's show coming up. It may not happen every day, but it represents the clearly defined dress-up games that we—and art—like to play.

This is sort of realistic. It's only a cartoon, of course, and I hear the movie bombed, but even the incredible Hulk can display firm drawing and shading in three dimensions. There is no question what it represents.

This is pretty unrealistic. We recognize the interior, and the woman's attempt to keep up appearances is out of a world we know. But few of us, other than the gentleman in the preceding slide, are yellow-green. Besides, we realize that it's a key step in Willem de Kooning's progress toward Abstract Expressionism. And after that? Now, it's just a painting.

But there's also Realism with a capital R. Make that at least two Realisms, in fact—one in France, just before the Impressionists, and one in America, a time of growth culminating in the urban realism before World War II. Both look so somber, so determined to bring us reality. No wonder they share a dark palette. Indeed, you probably caught my joke, in using a section from the George Bellows street scene for an example of abstraction a moment ago. I couldn't allow actual abstract art into the Academy, you see.

Realism, then, means many things. We may imagine a timeless truth—an artist's fidelity to nature and to what we see. We may imagine an art movement in its time. We may imagine observation suffused with memory and fantasy, as for Charles Burchfield. Or we may imagine a style and technique that can be learned in school to this very day—an alternative to abstraction or Postmodernism.

We may even imagine other criteria entirely, but I'll get to that later. Either way, though, there's just no getting around it. Contrary to the very spirit of realism, we see alternative realities.

Who, when, and where?

If realism in art has meant many things, how can we chart its shifting meaning? I suggest that we put aside the obvious—skill in light, color, anatomy, and perspective. Instead, ask how we got to all of those. Suppose we turn to the very start of realism in Western painting, as textbooks often define it. Let's step back for just a few minutes, I promise, before American realism, to the dawn of the Renaissance.

We're entering the arena, so to speak—the actual Arena Chapel in Padua. For us, it's a gorgeous day trip from Venice; for Michelangelo and so many others who drew there, it was a pilgrimage. This Last Judgment, probably the final work before the chapel's unveiling, may not look all that realistic to us now. It does not show off much of Giotto's own innovation and influence at its best—his men and women firmly on the ground, his way of making even the turn of someone's back evoke profound emotion.

Sure, a textbook will point out that, if you look closely, the angel's wings are as full and light as a bird's. The scene of damnation at the right is more modern still, and sorry that I can't show it to you better. But let's look instead at one small fraction of the scene, just to the left of the cross, at bottom center. Here Scrovegni, who funded the occasion, is presenting the chapel itself.

It's one of the first recognizable portraits in all of Western art. But it's more than that, for it places us in the world. It's an actual place, the very building in which we stand. It's a moment in time, the dedication of the chapel to the three Marys, a ritual in which we as well as the donor take part each time we visit and look. And it's a station in life, just as each and every row in that Last Judgment meant a ranking of men and women in heaven or in hell. Along with Scrovegni, the wealthy patron, whenever we come to this chapel within a chapel, we have a place in this community.

In other words, I want to convince you that modern realism arose as an imperative: you are here. It invites us to ask how artists have represented not just the world but us—who we are and, even more, when and where we are. I am not proposing a social history of art. Rather, I am asking how it became possible to speak of art in defiantly social and historical terms.

Giotto invites us to ask how that construction of ourselves changed, how it became so difficult, and what that means for looking at American realism today. I want to show you just how fast that question evolved. How did we get from Giotto to American realism? I'll take it fast—centuries at a time.

Getting into the world

Here's Jan van Eyck more than a hundred years later. Now we definitely have a sense of place. We have another donor, Chancellor Rolin, who looks as wealthy and viscous in his formal piety as I'm sure he was. We have the perspective of the floor tiles and an even more recognizable scene behind them. That's his city out there.

Why isn't it yet American Realism? For one thing, as with Giotto, we still live in two worlds at once. Giotto set a moment of dedication and ritual against eternal redemption. Here a familiar world stretches out before us as endlessly as both art and vision, while a unique enclave holds another kind of vision entirely. Most of the time, the painting says, we have our back to a higher reality, just as that anonymous pair in the middle ground, leaning on the balcony, turn their back on the foreground.

Compared to Giotto's world, there's been a big change, however, and not in technique alone. The two worlds are continuous and interpenetrate. The light from the city pours through the three arches symbolizing the Trinity and through the bottle glass—illuminating even God. It's part of a vision perhaps uniquely expressible in a new medium, the precision and translucent depth of oil. Moreover, we look forward, exactly like those two men, and yet we also look upon them, seeing what they cannot.

Now skip ahead more than two centuries. Jan Vermeer again has two worlds, outside and inside, and the inside is an allegory of an ideal, the art of painting. We again have the magic of unveiling, here with a curtain, and the unity of light.

However, the jumble of worlds has grown truly mind-boggling. The artist himself has his back to us in the foreground, and the muse is just a model. Painting and the perspective of floor tiling aspire to a map of the world. There is even a map of the outside world on the back wall—a reminder that the Dutch republic thrived on its command of the seas.

If all that seems old-fashioned, let me skip another two hundred years, to America at last. Here, along the river that I crossed myself an hour or so ago, Thomas Eakins maps the world with perspective. The oars, the single skulls, and the patches of darkness on the river form diagonals that, like Vermeer's, tile every square foot. There's even a sketch of this scene, overlaid with a dense grid that would intimidate computer graphics in Hollywood.

On the move

And now our journey to America and to modern notions of realism is complete. Max Schmitt in his single scull is looking out toward us, and we are fully in his world. It's the world of American realism, and it starts to take the mind games of a past age's metaphors at face value.

Since this is painting, looking matters. Looking is what places us where we are. It aligns us with van Eyck's citizens and Vermeer's brush, just as with Max Schmitt's cool stare. Here it is again—about eight years later with another American, Mary Cassatt, in Paris. In the theater we are all onlookers, all part of the same performance, the same passing show.

Not everyone, perhaps, dares look. Back with Eakins again, a man shields his eyes from the blood. But that emphasizes the immediacy, the gritty reality of this place and this moment. If you want to learn the anatomy lesson, you must look.

So we came, we saw, we conquered. At last, we can say that this is American realism. We are in the moment. But where? Take in turn each component with which I began—where, when, and who we are.

Where? In American realism, that means on the edge. Maybe for van Eyck it meant an edge between a continuous, untroubled present and another world. For America, it means an uneasy peace and mutual admiration between two aspects of the present—us and the wilderness. You can see it in the Hudson River School, with traces of exploration or of the new railroad that impinge on the apparently sublime scene. You can see it earlier, in a painting at the Academy of William Penn sitting in peace with the Indians.

With Impressionism, here in another painting from the Academy, by Ernest Lawson around 1910, it means a fence between patches of private property that is just barely holding up. With realism, from now on, not only are we on the edge, but that puts us on the line.

Sure, this side of realism extends past America. Scholars have pointed out that scenes by Claude Monet may look idyllic, but he depicts a new phenomena—places for the Parisian middle class to enjoy on weekends. However, for Europe, nature was part of a common landscape and a shared history, the proverbial playing fields of Eton that defined Britain as opposed to empire. In America, the boundaries are always on the move.

A New York moment

Where are they moving? Five years after Lawson, here with Childe Hassam, in a work here at the Academy, they still encompass nature and culture. Only now we look from firmly within a growing urban neighborhood to is apparently rural counterpart, and even that is Central Park. Hassam's typical dry white layer of mild impasto unites them all, even while the eye tries to assess the difference. Classic American Realism is now about one thing—the urban scene.

So much for a moment in space. How about that moment in time? If realism ever seems an eternal truth, try to imagine a painting before Romanticism with a title like Rain, Steam, Speed, by J. M. W. Turner. It's about capturing an instant, and it's also about a moment that could never have occurred before the invention of the railroad. I can't tell you how many times Monet and his generation painted train stations swallowed up in smoke. Or once again we have that painting by George Bellows, Steaming Street.

Realism loves the fiction of a moment. With John Peto, one can date the scene from each scrap of office paper, like email today. One can overlook that Peto has two dates on the painting because he returned to it and similar scenes over many years. Now here it is in 1928, on the back of something newer than a railroad and more particular to cities—the internal combustion engine. Charles Sheeler's I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold cites William Carlos Williams, the "Bill" at the top edge, and I have taken the liberty of quoting another line of the poem, "moving tense unheeded," to emphasize the urban moment.

In fact, a painting from the Academy by John Sloan, who spent years there himself, could stand for that contemporary idiom, a New York moment. It's a definite place. The el and that quaint tower in the middle define this as Sixth Avenue and Tenth Street, near where Sloan himself lived and exhibited. They defined that world in practical terms, too. The construction of the el in the late 1880s sparked the housing you see all around. By connecting uptown and downtown, it then encouraged a turn of fashion further north, allowing the decline into tenements that Sloan captures in so many shades of brown.

It's a definite time. If the el was almost a novelty, now it's gone, with the contract for a new underground line signed barely five years after Sloan finished, in 1917. That tower was a courthouse, which I remember terrified me as a child when my parents pointed it out as holding prisoners, and now it's a lovely public library with the old stained-glass windows. Most of the tenements you see around it, too, are gone. The problem with a moment of time is that it mixes so many possibilities that its demands for certainty must remain always unresolved. I know of no actual spot that could have allowed Sloan to see all this.

Where did we go?

The painting also introduces the missing piece of the story, who we are. Like this street corner, urban realism brought together the artistic avant-garde, slum dwellers, and everyone else who cared to pass by, each in a class of his or her own. For George Tooker, a subway was to become the scene of "magic realism."

So who are we in American realism? As far back as the 1880s, with Thomas Anshutz, we're in rough company. That's part of Realism with a capital R, rubbing our noses in a wider and wider circle of reality. These workers cling to their moment of leisure, and they use it not just for innocent athletics, but to show off to us and to each other. Remember that this is painting, so again, we're always looking.

We're at war—or at least in a tough fight. Bellows painted this boxing scene in 1909, although he recycled the theme even after the First World War. In the city of this art, it's often night, when strange entertainment comes out, but we're a long way from Mary Cassett's loge in Paris.

In the city, as in song, we're all alone in a crowd. Here is Edward Hopper, with Hopper's iconic image of the early 1940s, Nighthawks. Under artificial lights colors turn stranger and shadows deeper, making the sobriety, smoke, and shadows that connected Bellows to Gustave Courbet, say, increasingly a thing of the past. Photographers like Ron Diorio still take his images as contemporary.

In fact, with Oscar Bluemner's haunting color or Charles Demuth's turn to the very modern realism of urban factories, we're no longer there at all. No wonder the forms have retained the harshness of Eakins's perspective but lost entirely their depth. We are now just unseen cogs in the machine.

But where did we go? Is it a coincidence that historians so often call American Realism, too, something that vanished with World War II? If I have tried to describe Realism, what ever happened to it?

Finding Modernism and leaving home

You have no doubt heard the conventional answers. They all involve the triumph of American Modernism. I promised earlier to consider alternative definitions of realism that the Academy may exclude, and here they are.

As European Modernism came to America, in one version, it brought a universal style. Why bother now with a specificity of time and place, when "where" is an experience, an ideal, or an existential moment that belongs to all equally? Conversely, some critics, especially Marxists, have seen Abstract Expressionism as an expression of America's emergence as a global power.

Another answer involves the "expressionism" in Abstract Expresionism. Who needs the superficial, visible world when you can have what Andre Breton once called a "superior reality"? Surrealists aside, feminism was to make a strong case for more of humanity than the boxing arena and factory world we've been seeing today.

Last, abstraction, formalism, and later Minimalism and site-specific art transformed the "where" of realism in another way. When you become aware of paint as paint, art as object, and your experience as part of the same space, you really are here. How could we ever have come to associate realism with illusion anyway? Plato, for one, would have been horrified. Photography, some still feel, takes care of that habit of belief regardless.

And all these things are true, but are they the whole story? They suggest that realism outlived its usefulness and died, or at best it survived as a museum piece in dedicated enclaves like this one. And I think that's missing something, just as critics miss something when they say abstraction is dead now that it is no longer ideologically dominant and pure. I again want you to put the conventional answers aside for a moment. If my pocket history has any validity, realism has had the power to change. It has changed to take full account of Modernism's other "where"—and also from a logic very much its own.

Back to Demuth, with the move from country to factory, we have left our own home. In place of the ideal of the wilderness as a kind of lost Eden, we are exiled in what this painting calls My Egypt, and don't come asking the Pharaoh to let you go.

Moreover, just as urban walks displaced hikes in the country, after World War II the city gave way to suburbia, and realism had to change with it. Remember how we can pinpoint a real street address in Sloan's Greenwich Village? The urban grid, unlike Eakins's mathematical one, had largely dissolved.

The view from nowhere

In 1961, Edward Hopper is still, amazingly, as vital with the diner scene in Nighthawks nearly twenty years before. We could almost be in a scene of suburban transgression from Eric Fishl in the 1980s—or from Lisa Yuskavage and Yuskavage drawings today.

The woman is in her home, but metaphorically she will never be at home. Her bed is unmade. If the right stands for east, the light at this angle is harsh but also the crack of dawn. She will never have the relief of sleep.

She has her privacy and desires, but for whom? No signs of nature or companionship appear out the window in front of us. In a traditional Annunciation scene, a woman faces left, toward the light of God's own incarnation. As here, sometimes a saint has cast his shoes off, since he stands on holy ground. This woman, however, faces right and wears nothing. She has turned her back on all that, leaving nothing but her sexuality, in a disturbing isolation.

Another view of reality has taken over, not the view from realism's here or Modernism's everywhere, but the view from nowhere. And I say that deliberately, using a phrase that, unfairly I think, has been leveled at abstraction. The view from nowhere includes mass reproduction and created desire, as in Andy Warhol in Warhol's star-struck reality and Roy Lichtenstein's wistful appeal at once to comic books and fine art. I lumped Demuth's fire truck with realism, but its overlapping forms could just as easily belong with Cubism's influence—or with the influence of magazine illustration in Pop Art many years later.

Robert Rauschenberg sure seems to belong to the moment, like old-fashioned Realism. This great painting all but leaps out of the headlines. Even for many who grew up too late to have experienced them in person, it combines the modernity of the space shot—a moment later than the elevated train but just as specific—with the lost idealism of the Kennedy era.

It, too, however, exploits a reproducible medium, silkscreen. And that scene at the lower right is an expulsion from Paradise, out of art history. Together with the space capsule it reminds me of a moving line from J. Robert Oppenheimer after Hiroshima: "the physicists have known sin." The painting conflates present and past, as if this moment never fully exists in its own right and as if neither past nor present can ever be recovered for us. It is no accident that the painting is called Retroactive.

Who's looking?

Is that it, then? Was that realism? Is the present now all in the past, as in portraits by Barkley L. Smith that quote fashion and the Renaissance on equal terms? I shall stop deliberately around 1960, to leave open 40 years of possibilities. Only the painters of today can answer to them, and I hope some of you will try. But I want to leave you with new ways to see them. Here are two thoughts from writers I admire.

The first is from a West Coast critic, Rebecca Solnit: "Landscape was not significant in modern art." This lecture has tried to convince you of the opposite, even—or especially—if that takes expanding the whole idea of landscape from a view of nature to a view of our place in the world and the imprint artists leave on it.

The second is from a letter from Lawrence Weiner, the conceptual artist, to Ed Ruscha, the LA painter and photographer, about a book on which they were collaborating. He hoped that it would demonstrate "the noncontemporaneity of contemporary art." I have tried to convince you that, as you look at all realism, you have to pin down just what a word like contemporary means for that artist, for that work, for its time, and for you.

Together, the two quotes also help explain why Renaissance ideals with which I began, of truth to Nature, evolved not just to different art movements called Realism, but also to a widely shared popular believe in realism as more than a style. We want to know who we are, we want to believe that we do know, and we want art that we can trust to assure us that it's possible. Solnit invokes that same nostalgia. Your job is to relish it, too—and to question it.

When you come to a talented contemporary artist, such as Bo Bartlett coming here in less than three weeks, never to ask only how realistic the work is. Stay specific about which realism and yet loose enough to recall other realities, because realism has meant—and still means—so many things.

Ask what reality it creates—and how. Remember that someone's always looking in art, but where, when, and who?

A postscript: Bo Bartlett's world well lost

Finally, since I have a few minutes left, let me suggest how Bartlett may fit into the story. I can only guess. He was unknown to me until recently—frankly, until the Academy got in touch. I have seen his work only in reproduction, and I'll be discovering it along with many of you here this fall. I can, however, say that he seems very much caught up in the conundrum of the future of American realism.

This one's called Eden, the world that an expanding America has perhaps well lost. The girl has a dress out of some 1950s' ideal—or maybe the remake of The Stepford Wives. She has a wreath that identifies her with nature or poetry, depending on who is keeping score. She also is far from those ideals, however. She is playing on a tire, with an athleticism once more reserved for boys, and the house is peculiarly far away. She could almost be in someone else's backyard.

This one, called Magic, has all the obvious disabuse of clichés about childhood alongside a heartfelt affection for them. It's an old-fashioned yellow bus, but one boy is smoking, and others are using the window for graffiti or just for scowling. It is very contemporary, from the integrated passengers to the cynicism. On top of that, it's part of that world in transit I have tried to describe. A bus is a place between places, there is no ground or sky, and the words on the side of the bus are cut off.

One last image for you. This one is even called The Good Old Days, and it seems only partly sarcastic about its claim. The family looks reasonably close, with the good fortune to share costly leisure activities. The father can boast of reeling in the big one. Still, one shakes one's head at first—at the family and the eerily vacant expanse behind them. Is this the traditional two-child family portrait, but with the mother replaced by a large dead fish hanging upside down?

As always with Bartlett, the light is a little too dark and washed out—and meaningfully so. The smooth skin shading from red to olive may belong better on space aliens. As I say, we take for granted that realism is just adherence to classical technique and to nature. But a change in subject or in point of view always changes the how along with it.

Anyhow, I can't promise what we'll find starting September 18, but I can always hope that you'll ask enough questions to make your own discoveries. And if you're short of enough skepticism about reality, there's always cyberspace. My site has hundreds of essays in review, and I hope you'll visit.

I delivered this lecture September 1, 2004, without notes, but this text, prepared in advance, comes very close to snagging it. "Heartland: Paintings and Drawings by Bo Bartlett, 1978–2002," ran at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts through November 14.