Experimental Photography

John Haberin New York City

Harold Edgerton and Sheila Pinkel

László Moholy-Nagy and Barbara Kasten

Remember when photography was a science experiment? It need not even unfold in a laboratory, like motion studies for Harold Edgerton, not when Modernism was itself an experiment.

Sheila Pinkel conducted her experiments with little more than glass rods and folded paper. Still earlier, László Moholy-Nagy chafed at the limits of box cameras and black-and-white prints. Edgerton burst limits of his own in motion studies—sometimes with a bullet. Barbara Kasten starting in 1979 plays with light and space, starting with overprinting and Plexiglas, while more recently Owen Kydd slows the pace of the city. Who can say which looks closest to today?

Moving images

They say that Eadweard Muybridge invented stop-action photography to settle a bet. Harold Edgerton just wanted to know how much damage people could do. He shot bullets through playing cards, Plexiglas, and hot-air balloons. He scrambled eggs and photographed the empty shells along with the bowl and the swirls. Not that he confined the damage to his alone. He captured a nuclear explosion in 1952, the year that the hydrogen bomb changed the stakes of the Cold War to sheer survival.

Even when it came to sports, he took the measure of deformity, if only for an instant. He showed just how far a hardball, golf ball, or football gives way at the moment of impact. It is not far or long, but it is more than you knew. Precision matters, in an art of small differences—just as a century before for Muybridge, who confirmed once and for all that a horse's four legs leave the ground at once. MoMA included both men in a show of "Photographic Practices in the Studio," but Edgerton had his studio at MIT as a professor of electrical engineering, beginning in 1934. Muybridge was a pioneer, but Edgerton was a scientist.

Still, he was arguably the more self-conscious artist. Muybridge traveled between England and the United States back when photography had to prove itself as an art, much as for Julia Margaret Cameron, and he broke things down frame by frame like a slide show or a lesson. Admirers have noted his influence on the birth of motion pictures and "a new kinetic art." Edgerton made each image a compendium of motion and a lasting impression, with contributions to Life magazine and with a full awareness of their strangeness. Others have included him in shows of "Ghosts in the Machine" and American Surrealism. He thrived when going to the movies was becoming a ritual, and he was happy to compete with them for effect.

A small show focuses on the artistry and the strangeness. The documentary impact of an A-test is out, along with the playing card, and the swirls and shadows are in. One may never experience contrasts this sharp outside of a laboratory or a photogram, and one may not even know half the time what one is seeing. (Do those swirls and eddies really belong to tennis?) Multiple flash units track a bullet's path through air from its shadows alone, as if through sand and smoke. It might be the universe in a grain of sand, as for William Blake, but the grain is itself an illusion.

Athletes here have their own self-conscious artistry. The muscleman with a baseball bat could well be posing for the camera, and the multiple reflections of a gold club surround the golfer like flower petals or echoes of his body. Even the title sounds artier than needed, Densmore Shute Bends the Shaft. Most of the images go back to the 1930s, starting with water from a faucet in 1932, although prints mostly date to the year before Edgerton's death in 1990, but if anything they become showier. The bullet leaves one balloon in shreds, in 1959, before bursting a second and passing neatly through a third. Well into the nuclear age, he is still measuring the damage.

Was he first, then, an engineer or an artist, a journalist or a connoisseur of chaos? Was he even a photographer? He actually contributed the technology of strobes and "shadowgraphs," working in collaboration with Gjon Mili. Are the displays of athleticism a self-reflective boast of virtuosity, and is the dog begging while wagging its tail the confession of a born entertainer? For all the air of danger, Edgerton shares the exhilaration at once of Modernism and scientific discovery. To make an omelet, you have to break a few eggs.

Paper, glass, and fireworks

Even when art meets science, but Modernism was about more than the triumph of pure reason. Of course, past experiments had included photography's origins, in the confluence of chemistry and optics to capture sunlight. They included stop-action photography well before Edgerton at MIT. Think instead, though, of the 1920s and 1930s, when a photographer's studio could resemble an eighth-grade science fair—with simple equipment and a child's wonder at the strangeness of life. Think of the very image of a child in its mother's arms for Alexander Rodchenko, on a grand stairwell reduced to alternating strips of black and white. Or think of Man Ray, with his only lens the mind's eye, for whatever came to hand on photographic paper exposed to light.

Sheila Pinkel looks back to their uncanny mix of naiveté and sophistication, and she could hardly mind if the results seem awfully slow in coming. She emerged slowly herself. Born in 1941, she began her experiments as an MFA student at UCLA—where she studied with Robert Heinecken, for whom technical and cultural innovation meant television. After years teaching at Pomona, she is having her first New York solo show, with photograms from between 1974 and 1982. One series records patterns of light and color refracted through glass rods in tight parallel. The other ditches everything but the treated paper itself.

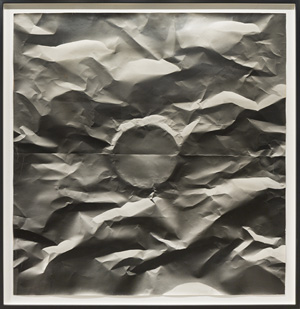

The glass series, like photograms by Aspen Mays as well, revels in the look of an earlier avant-garde, including cold reds and greens from early abstraction and strong contrasts of black and white. Jaromir Funke had based his photograms, too, on bottles and glasses—and another Czech photographer, Jaroslov Rössler, started as a lab technician during World War I. Pinkel's diagonal arrangements are obvious enough, and their interruption by shadowy clusters are almost inexplicable. For the second series, she crumpled paper, gave it the impression of circles from, I imagine, a drinking glass, and folded it neatly in quarters.  Then she had to flatten it again in order to make prints. Sheets can look as palpable as trash or as smooth as geometric abstraction.

Then she had to flatten it again in order to make prints. Sheets can look as palpable as trash or as smooth as geometric abstraction.

If Pinkel looks back, László Moholy-Nagy looks to the future. Born in 1895 in Hungary, he taught at the Bauhaus, where all of modern life was an experiment, but he stands curiously apart from the everyday. His color photograms have no recognizable subject beyond themselves, in looping traces of light like a fireworks display. He might have executed them just the other day, long after his influence on Bauhaus photography. And so in a sense he did, for the technology did not then exist to make these prints. Liz Deschenes has brought them to completion, and they now belong to her and others now working on the "strange magic" of art between photography and painting.

The entire show has as much to do with Deschenes and others today as with Moholy-Nagy, sometimes at his expense. The curator, Erik Wysocan, calls it "Production / Reproduction" after a 1922 essay by the artist, who died in 1946, but its focus is not the fabled "age of mechanical reproduction." It is about changing technology as a means less of reproduction than displacement. Moholy-Nagy wrote of wishing "to receive and record various light phenomena (parts of light displays) which we ourselves will have formed," but then he did not fully form the images. He must have taken three slides of his family, left out on a shelf as if by neglect—but not his portrait in a striking color print seated at a table in an open field. He appears as a creator, but also as a subject for history.

It is not an easy history to follow. Another shelf has several Leicas, one a garish gold, because Moholy-Nagy adopted the hand-held camera fifteen years after his essay—and because Soviet knockoffs of Leicas later flooded the market (as, I presume, production / reproduction). The shelf also holds a chunk of silver bromide, because photography was a chemistry experiment, but photos here are way too few. At least one can contemplate them from a four-sided bench that he himself designed, again in reproduction. It is not in galleries and museums everywhere, Wysocan argues, because it looks too much like a swastika, but you could have fooled me. The only certainty is that photographers will always be experimenting, while looking both forward and back.

An experiment with light

More than thirty-five years ago, Barbara Kasten threw everything she could into photography, at times even a photo. Talk about double exposures. Her Amalgams from the late 1970s combine photograms with conventional prints, created and enlarged within the spooky confines of the darkroom. Often she topped them off with paint, for true blackness and slim lines or arcs of color. Their orientation relative to the edge of the paper helps to ground an image slipping in and out of the third dimension. They are also a record of what that recent survey at MoMA, Kasten included, called photographic processes in the studio.

That third dimension is not strictly an illusion, not when a photogram relies on the direct imprint of an object. What looks most illusory, in fact, is the most straightforward representation of depth—in images of, I am guessing, wire constructions. Off-center cubes seem to surround and gather light. Conversely, the most literally three-dimensional element, the paint, comes closest to the picture plane. Born in 1936, Kasten had been at it for a while, including Polaroids displayed in the 2013 Armory Show, and she had a long memory. The abstractions update Moholy-Nagy for Minimalism.

Her gallery would add the "Light and Space" movement, although Kasten had her darkroom east of Southern California. And if the Amalgams seem a little too dark or fussy, leap ahead to the present. She introduces them with larger photos from 2014 of tumbling Plexiglas constructions filled with light and color. At the same time, these Transpositions adhere less obviously to the vertical, bringing her closer than ever to early Modernism. In this version of experimental photography, every print is an ongoing experiment. It just happens to sit still.

Kasten's latest does move, only slowly. Sideways leaves a back wall mostly black, interrupted by nothing more than light. The light's intensity follows naturally after the translucency of Plexiglas. The projections sometimes echo the architecture, as if the four corners of the room were marching across the wall. At other times pie shapes open and close. The video uses repetition and variation to slow one's perception. It also adds one more stage to an experiment with light.

Owen Kydd places his "Out-of-Place Artifacts" in actual light boxes. His images move slowly, too, but not as Kasten's strict abstractions. Kydd sticks to the city, indoors and out, give or take the intrusion of nature. In his most puzzling video, people do seem to be up to something in a more or less open landscape, although just what is hard to say. Consider it an invitation to resist narrative—and to resist locating his settings in one's past. It also has one looking all the harder for change.

Change does come slowly. Mist fills or pours out of a corner, while household utensils in color recall the still-life photography of Jan Groover. A knife gives way to a feather, and a metal ring, maybe like the ones supporting a shower curtain, casts its rotating shadow on a wall. The most abstract, though, also sticks most firmly to the city. Shadows play across pavement splattered with white, a shape like the police outline of a body. As for Edgerton, photography has to perform its experiment with people.

Harold Edgerton ran at Sikkema Jenkins through March 7, 2015, Sheila Pinkel at Higher Pictures through February 21, László Moholy-Nagy with Liz Deschenes at Andrea Rosen though February 28, Barbara Kasten at Bortolami through May 2, and Owen Kydd at Nicelle Beauchene through April 19. (A related review takes up László Moholy-Nagy in retrospective.) Portions of this review first appeared in a slightly different form in New York Photo Review.