Some More Trees

John Haberin New York City

Babs Reingold: The Last Tree

Mary Hrbacek, Kris Graves, and Terry Evans

Not so very long ago, Ellen Altfest's meticulous painting, now in the 2013 Venice Biennale, was introducing me to a tree as a complex ecosystem. Anya Gallaccio was giving that ecosystem a history, of destruction as much as growth. And Tacita Dean was joining photography and painting in a celluloid elm with a life of its own.

Not that landscape painting is a novelty, and not that observing landscape has ever been a neutral act. Nations have defined themselves in claiming the land as their own, and landscape painting became part of that self-definition. These artists, though, scrutinize the land up close, as if under a microscope, to find both a human creation and a parallel life form. I found myself quoting the most postmodern of American poets, John Ashbery, to join in his "amazement." For Ashbery, "you and I / Are suddenly what the trees try / To tell us we are." These artists say instead what trees are, as beings apart, with lives of their own.

Six or seven years later, Babs Reingold and Mary Hrbacek make those themes even more explicit. Together, they link trees linked to the sad fate of civilizations and human loves. Meanwhile photographs by Kris Graves and Terry Evans give the human landscape a context in time and space. Neither needed Photoshop. Graves simply went to Iceland, while Evans simply took to the air. They become part of the scene all the same.

A tree grows in Soho

"What do you imagine the Easter Islander was thinking when he chopped down the last tree?" If he were an artist, he might have imagined more. Babs Reingold does not have need to rely on genetic sequencing or even basic horticulture to create her own. She transforms a gallery into a brooding field of stumps, using little more than silk and human hair. They could be savagely cut off or coming rudely back to life. And presiding over them all is a solitary last tree.

Reingold finds inspiration in that quote from Jared Diamond. The scientist and author has long insisted that the environment guides the fate of civilizations, more even than genes or culture. In Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, he points to twelve devastating issues for the planet, starting in fact with deforestation. His question, though, puts them in thoroughly human terms, as well as in the form of a mystery, and so does Reingold's The Last Tree. She sets out a regular array of one hundred ninety-three buckets, one for each member nation of the UN. Each serves ambiguously as a planter or final resting place for a tree.

They are convincing trees at that—and, like branches in a classroom for Hugh Hayden, not altogether dead. Their irregular shapes include tendrils, often punching right through the side of a tin bucket as if on their own. The artist stains silk organza with tea and rust, sews it, and stuffs it with hair, collected over time from hair salons. Additional dark hair lies to all sides within a bucket. Spirals of lace and thread on the top of a stump bring out the creative process and a sense of growth. The single taller tree seems to stand from the force of its stuffing alone, although it has an assist from a clothesline above.

Reingold offers a natural history of the earth, but also a personal history. The fragile materials and sewing testify to a human life, while each lock of hair has its own DNA and its own history. The artist notes the Victorian custom of preserving hair in lockets, as reminders of love and death. Perhaps the clothesline reminds her of life in the projects, where she passed part of her teens. One more human presence enters on video, chopping down a tree but seen only as hands, her husband's. It looks like hard work, too, on unresisting wood, even with a nasty two-bladed axe.

The Last Tree serves as both performance and installation, like the uprooted tree bursting into a gallery skylight by David Brooks, his machine in the garden, or the layers of earth in photography by Letha Wilson. The Minimalist geometry of rows on the floor and their organic form also recall Eve Hesse, who knew how to give one the creeps. As with Hesse, too, or Louise Bourgeois, the materials and their physical presence relate at once to Surrealism and a woman's art. You may not yourself figuratively save a tree: Reingold sees the installation as a totality, like the planet, where another artist might sell individual buckets at the end of the show. Who I am to say which approach best preserves and disseminates the work in the world?

One can argue with Diamond about the fate of Easter Island. After all, he can hardly ask the statues on Easter Island—or their offspring by Ugo Rondinone in Rockefeller Center plaza this summer. Scholars have laid the blame on simple overpopulation (one of the twelve points on his list) or to disease-bearing Europeans, neither one a simple matter of blind choices and material exploitation. And population growth has little to do with an alarming twenty-first century spike in consumption, pollution, and global temperatures (another of Diamond's talking points). In the end, his answers are a bit all over the map but mostly about home in the West today, and one could say much the same about Reingold. The Last Tree, even at its most threatening, describes not an ending, but memory and growth.

What trees really want

In Dante's Inferno, in the seventh circle of hell, suicides have become trees, with harpies eating away their leaves and nesting in the branches. It is a pain lasting through eternity. For Mary Hrbacek, too, a forest has human longings. She gives trees human limbs and gestures. They reach out, often toward one another, and at least once they touch. Now and then, they may even find creature comforts.

Hrbacek did not have The Divine Comedy in mind or a watercolor on the theme by William Blake. She has no harpies, although goats nestle in one small acrylic. Where Blake hints at beings trapped within sturdy trunks, in one case upside-down, hers are the trees—their temptingly familiar forms all right side up. Still, her titles speak of unfulfilled desires, Reaching and Imploring. The twisted, leafless branches contain demons. She mostly cuts her trees off from the ground, much less from their roots.

They are not just suffering. The associations in her artist statement run from fantasy to her favorite tree in Central Park. The paintings, too, are neither entirely naturalistic nor folklike. Skies run to mostly flat backgrounds in shades between silver, blue, and green, and one title accepts graciously how much the bark looks like camouflage. The ambivalence extends to trees as monarch and wanderer, witch and bewitched, and she clearly identifies with both sides of the story. Most are women, but their sensuality does not depend on that.

As with Lisa Yuskavage, one could grow skeptical of the drama, along with the occasional boobs or butts. One tree has the smile of a cartoon lizard. For all that, Hrbacek is softening contours and extending her range. In her latest, she smudges charcoal into paper, creating multiple blacks, and one painting, unstretched, extends from floor to ceiling, cut from an eighteen-foot roll of linen. It also has gradations of light in the sky and no hint of a face. As it happens, the greater naturalism goes with more extreme gestures, particularly in charcoal, but also in the nine-foot tree's thin limbs and the hollow stump of a lost branch.

Louise Dudis is on still more intimate terms with trees, but the real thing. As her show puts it, she brings one at "Eye Level with the Smallest Leaf"—and then some. Her camera picks out the texture of bark and lichen like pigment on canvas, with the leaves a firmer background. She does not, however, work small. Successive prints set side by side create a larger panorama from a single tree, the small gaps between them bringing the picture plane that closer. One could mistake them for a fisheye perspective except for the mass at the center, and one could mistake its twists and turns for taking place in real time, only the motion is all hers then and yours now.

These artists are closer in spirit to Romanticism than to the contemporary urban and suburban theater of John Currin. And American art has a long history of parallels between human relations, humanity and the land, and art and nature—what Asher B. Durand called Kindred Spirits. The Hudson River School, the Met has argued, left the ultimate expression of sorrow and reconciliation after the American Civil War, while Sylvia Plimack Mangold uses trees to bring old-fashioned painting to the ecosystem themes of "Expo 1: New York" at MoMA PS1. I have always thought that Dante's punishment for suicides is unbearably harsh, given that they would not have come to their fates without suffering in life. At the end of Purgatory, though, he comes to another tree, the Tree of Knowledge, and allows it to bloom.

Crossing Earth

It can be hard to believe that Kris Graves does not need Photoshop. Near cylinders of ice float across a photograph, because they float across the island. One can imagine a photo collage—a reference to nuclear silos, Richard Serra, or late Le Corbusier. They look far too large, far too perfect, and far too close to the picture plane for anything less. Their glistening white detaches them that much further from the background, although they belong quite well enough where they are, amidst rocks and water. They could still fit almost neatly together, like pieces in a puzzle.

Graves had plenty of time to solve the puzzle, during three years in Iceland, and to discover more. A red and white church seems to hover above a field of snow, like a human counterpart to the northern lights. A rock face up close seems molded from acrylic, like the paintings of parched rocks by Llyn Foulkes. A narrow highway cuts through ice and snow, much as a broad river cuts a canyon and waterfall through the earth. Mists bubble up from the ground as if storm clouds had touched down from the sky. Graves remembers the smell of sulfur at 3 A.M., but then this country does not appear to have the concept of night.

Graves had plenty of time to solve the puzzle, during three years in Iceland, and to discover more. A red and white church seems to hover above a field of snow, like a human counterpart to the northern lights. A rock face up close seems molded from acrylic, like the paintings of parched rocks by Llyn Foulkes. A narrow highway cuts through ice and snow, much as a broad river cuts a canyon and waterfall through the earth. Mists bubble up from the ground as if storm clouds had touched down from the sky. Graves remembers the smell of sulfur at 3 A.M., but then this country does not appear to have the concept of night.

It helps the illusion of illusion that the photographer, an African American and a New Yorker, has a good eye. He finds the yellow, green, and brown tints in landscape that thinks mostly in black and white. He cares about composition in a region of volcanic activity that will not sit still. That region also spans Europe and North America, and Graves pairs the two sides of the divide in two more photos. Maybe global warming helped split those two glaciers, just as it is splitting off Arctic ice, or maybe not. Things are unstable enough as they are.

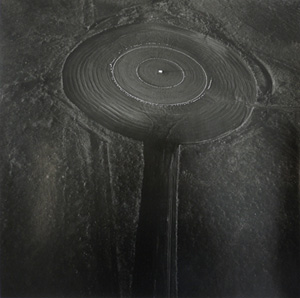

Terry Evans finds something almost as impersonal in the American Midwest, but she also calls it home. Maybe it keeps her honest that she, too, has photographed glaciers, in Greenland. She adds her own note of impersonality by relying on aerial photographs as well. One can almost overlook that it is the point of view of a human observer—what the curator, April M. Watson, calls "the humane perspective" of her "aerial landscapes." Evans sticks to the twenty-five miles around her home in Kansas, like Robert Adams casing out his own neighborhood. She takes to the air to find the facts on the ground.

She even calls her series from the early 1990s "The Inhabited Prairie." It includes farms, ranches, and industry, an Air National Guard bombing site and a nature preserve. It probably received an agricultural subsidy one of those GOP amendments that cut food stamps from the last farm bill. A highway makes much the same swerve as in Iceland. And Evans has had series on the oil business before. Yet what she finds does not look terribly inhabited.

She, too, is tracking the shifting relationship between art and the environment, interiors and landscapes, or nature and culture. She speaks of "layers of use, layers of loss and recovery and loss again, vestiges." The distance from the air allows her to "read" their signs, and they look both beautiful and not so easy to decipher. One thinks of humanity as encroaching on nature, but here nature surrounds and isolates humanity, leaving circles or squares within a seemingly infinite domain. They might as well be crop circles left by extraterrestrials, except for one thing: Evans is the one visiting from the air.

Babs Reingold's "The Last Tree" ran at the ISE Cultural Foundation through June 28, 2013, Mary Hrbacek at Creon through April 30, Louise Dudis at Robert Henry Contemporary through April 28, Kris Graves at Pocket Utopia through July 26, and Terry Evans at Yancey Richardson through July 3. Ellen Altfest, Anya Gallaccio, and Tacita Dean are the subject of an earlier review, "Some Trees."