Arsenals and Empathy

John Haberin New York City

Sarah Frost and Liz Magic Laser

Henry Taylor and Darren Bader

It is not often that Carl Lewis and a live iguana share a museum. (Were you waiting?) Now each has become a work of art. Better yet, make that political art.

What is political art, and is it even possible? Lots of people have answered no, as if much of art history were not political. They have seen the very term at odds with itself. Either art matters, in which case politics distorts its very purpose—or, for some, its essential lack of one. Or else politics matters, in which case art is at best propaganda and at worst a waste of time. And of course political art keeps coming, as artists keep finding new ways to work in the gap between art and life.

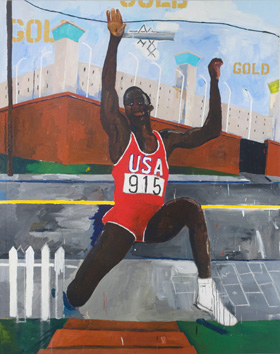

This year's models offer plenty of chances to flesh out that answer, with links to past versions of yes. Sarah Frost starts on the side of shock and necessity, with a ghostly arsenal, and then the ghosts take over in a delicate white paper display. Her extremity and nuance suggest why politics can harp on the culture in gun culture. Liz Magic Laser, too, begins on the side of hard realities, with performances based on politicians and their attempts at communication, and then the fun begins. As for Olympic athletes and exotic pets, Henry Taylor and Darren Bader never connect the dots, but they mean well. As an African American, Taylor looks for role models not to political leaders alone, but to artists and friends.

Gun culture

Political art thrives on extremity and outrage. From Artur Zmijewski on the Holocaust and Krzysztof Wodiczko, Shirin Neshat, or Yael Bartana on the Middle East, it keeps returning to a cacophony of sudden explosions and competing voices. As with terrorism for Gerhard Richter and Richter's late work or the aftermath of Katrina for Sara VanDerBeek and Kara Walker, silence is quite literally death. When quiet comes, as after 9/11, it comes as "a knock on the door." And surely America has a culture of violence. Where, then, are the weapons, and where is the random, the senseless, and the everyday?

Sarah Frost has an entire arsenal. It fills a gallery from floor to ceiling, in a ghostly white, with not a body or an explosion in sight. White paper guns hang suspended from threads, but with an equally ghostly realism. Their converging walls create a complete and welcoming environment while physically barring passage into the white nothing that is. In both ways, they suggest a monument to the dead not unlike the Vietnam War Memorial by Maya Lin. Paper cones lie piled in a corner on the floor, like spent shells.

Hans Haacke and Thornton Dial may have displayed the flag, but Frost could claim a more singularly American testimony. It began with her own discovery of gun culture online, where boys showed off their meticulous paper replicas of everything from "Grandpa's six-shooter" to heavy-duty automatic rifles. All she had to do was follow directions, and she sure did. The back room has photos of the kids, along with shelves for more paper paraphernalia, including bullets, a knife, and gun sights. However, she has taken at least as much care, to the point that one could mistake the white for painted sheet metal.

Outrage often comes a little too easily. "Arsenal" first showed in St. Louis, where the artist lives and works, but one could write it off as politically correct shock at discovering the heartland. For that matter, one could write it off as a woman's perplexity that boys play with guns. I had toy guns myself, and I seem to have grown up all right. One could even question what she adds to the replicas of others or who she can detach herself from what she appropriates. Others, too, will want to linger to inspect everything, but fear to touch.

Yet she has very much added more, starting with the care—and the ambivalence. She adds scale, to create an installation in its own right and with its own metaphors, although darned if I know for sure what to make of the cones. She adds attention, to a phenomenon that may well differ in quality from an old-fashioned toy store, much as Laurie Simmons or Morton Bartlett plays with dolls and with visions of childhood. She adds the specifically American and specifically normal, a reminder of what much political and documentary art omits. Most of all, she adds a sense of wonder. Just do not bring a water pistol, because you know what it would do to paper, and be careful where you step.

As for Wodiczko, he returns to a war zone in search of violence, but also, like its victims, in search of normalcy. Only low murmurs and a slim horizontal strip of light break the darkness. The implied window converts a square into a refuge—ambiguously a home or a bunker, interrupted by a helicopter, a child at play, and ultimately an explosion and a cry. It takes waiting, and one can feel that either too little happens or too much. That, however, describes the Iraq war, whether for American soldiers or those who live there. That leaves whether he has imposed a narrative on a video loop and on perhaps the ultimate safe haven of a beloved Chelsea gallery.

King Tut feels your pain

Liz Magic Laser kept people waiting, and as the doors finally opened they stood elbow to elbow, straining to see. Were they hoping a glimpse of the artist—or of the truth? Laser was typically reserved when it came to both. A single performer towered above the crowd, hair cut short, her features taut. Her jagged movements resembled the most extreme modern dance or the sternest lecture. I left before a second dancer could join her, but they felt more human the week after opening night, on video, facing each other down from opposite walls. And the artist does call the work, live or recorded, The Digital Face.

Whose face? Laser had her cast, Alan Good and Cori Kresge, mime the body language of Barack Obama and George H. W. Bush in their televised State of the Union messages. Digital, she explains, really means fingers, as in a certain theory of oratory from two hundred years ago. If their gesticulations look harsh, the presidents sought to communicate empathy. If they also look calculated and efficient, would it be wrong to think instead of Steve Martin's King Tut? Or of Hans Haacke attempting irony?

Of course, the joke would be on him, but Laser can take anything in stride—except corporate or consumer America. She stood out in the dismal "Greater New York 2010," with robot arms performing surgery on a purse crammed with credit cards. I somehow missed performances of a Bertolt Brecht play about an innocent caught up in the military, staged at a bank's ATMs, or of a woman dragged along the sidewalk until her nice new jeans tore. Laser collaborated last year with another emerging artist, Simone Leigh at the Studio Museum in Harlem, on video of an opera singer caught between theater and tears. Even her name sounds ambiguously mocking and self-important but apparently is real. Political humor has rarely been so unsmiling, and political art has rarely been so blatant a farce.

Now she turns from economics to politics, assuming that those are different. And which is it—reality, theater, or a grim joke? As ever, she is not telling, but empathy is disturbingly not in short supply. The sole other video, I Feel Your Pain, began as commission for Performa 11, the performance biennial last November. Eight actors sat among the audience in the School of Visual Arts Theatre, where they confronted one another with, it turns out, quotes from the usual suspects of both political parties. Laser compares the staging to Soviet agitprop, but I thought of a self-help meeting with its promise of healing faded and its charismatic leader gone for good.

Still not convinced that the joke is on anyone but you? I almost dreaded seeing the show, and I almost fled in a kind of mutual disdain—but I came back. The dilemma always dogs political art, which works best when the personal is the political, as with Sharon Hayes, but also something more. It did not work, say, last year at Exit Art, when a show on theme of fracking grew way too large and drilled way too deep. Artists used their single work either to say the obvious or, by displaying their usual, saying little at all. Now one of its curators is back, with a solo show, and the focus contributes both the personal and the political.

A sketch by Ruth Hardinger could pass for an abstraction, a landscape, or a cross-section of the earth. All those run through her work, along with the tactile sensation of all of them being disturbed—and not solely by hydraulic fracturing in search of fossil fuels. What looks like oil on paper turns out to be graphite, plaster, pastel, and milk on cardboard layered or torn at its center. Sculpture consists of concrete or plaster poured into awkwardly bent molds, bits of their cardboard still visible after she has torn the rest away. They look like an industry geologist's core samples, only gone limp. They retain their weight all the same.

Day of the iguana

As for Carl Lewis and an iguana, sure, purists may complain, but public figures and arboreal lizards have to share a thick skin. Lewis, for one, has entered politics before, although New Jersey ruled that his Senate candidacy violated a five-year residency requirement (or perhaps five years on Jersey Shore), and he has supported his share of worthy causes. Henry Taylor, though, paints him as still a track star, in full stride, the word GOLD twice in the air behind him. He looks so familiar as an Olympic athlete, an African American, and a controversial role model that it takes a moment to notice the penitentiary looming across the street behind him. He seems to float above the entire scene, like an image borrowed from the media, but he runs right into the picture plane—up steps and toward the bare hint of a one-family house. Is he escaping, coming at you, or returning home?

I cannot swear that even Taylor knows. He stops just short of social commentary, as if good intentions will take care of themselves. An entire "forest" of broomsticks, topped with plastic jugs painted black, may look ominous, slapdash, or just cute. It may display an artist's pride or his sadness at blacks trapped in menial jobs, just as his stack of Cobra malt liquor boxes on a rocker, all topped by a black head, may stand for empowerment or entrapment. He paints Huey Newton astride a chair like a Third World revolutionary or petty dictator, Eldridge Cleaver in profile like Whistler's mother, and Andrea Bowers without her art. Ever since Bowers wallpapered a gallery with feminist posters, I have been trying to sort out its obviousness, playfulness, and anger.

I cannot swear that even Taylor knows. He stops just short of social commentary, as if good intentions will take care of themselves. An entire "forest" of broomsticks, topped with plastic jugs painted black, may look ominous, slapdash, or just cute. It may display an artist's pride or his sadness at blacks trapped in menial jobs, just as his stack of Cobra malt liquor boxes on a rocker, all topped by a black head, may stand for empowerment or entrapment. He paints Huey Newton astride a chair like a Third World revolutionary or petty dictator, Eldridge Cleaver in profile like Whistler's mother, and Andrea Bowers without her art. Ever since Bowers wallpapered a gallery with feminist posters, I have been trying to sort out its obviousness, playfulness, and anger.

Mostly, though, Taylor depicts them all as family and friends, and they mostly are. A few dozen hang Salon style, as if tossed off the day before, but then he rarely looks back. He works fast, perhaps two hours a sitting, and almost the entire show dates to the last five years. If portraits have bare spots, broken lettering, or a black mark in place of an eye, think less of parody, Pop Art, and agony in Larry Rivers. Think more of an excess of vague sympathy. Think of Nike ads by an uncharacteristically lazy Alice Neel.

Oh, and did I mention a lizard? Unlike the portraits, he definitely makes eye contact. We watched each other closely for some time, the iguana out one parietal eye. (Yeah, go ahead and look it up.) Otherwise, he did not budge one bit. Obviously territorial and plainly satisfied beneath its UV lamp, he was not going anywhere, which is what these creatures do after a good meal. For all that, he is quite able to leap down a tree branch to the bottom of its Plexiglas cage for its herbivore diet and habitat.

One can actually adopt him and take him home, although not in New York City, which has certain rules protecting you, me, and wildlife from each other. One can also adopt any of three cats, and Darren Bader will replace them as needed to keep his show going through its run. He means to call attention to the plight of animals, and another room encourages a diet more like the iguana's, with vegetables on pedestals—looking as if they, too, were hardened by abandonment and time. Twice a week the show serves up free salad, although it looks rather averse to human contact. So, for that matter, do the cats. What with strangers tromping in and out, they hide in or around their covered litter boxes, in a corner behind the entrance.

Bader calls the show "Images," but it is way short of images, just as it may seem short of cats. Another room invites celebrities (none specified) to become the show, but I had the installation to myself. Like Taylor, Bader means well, and yet there has to be a better way to protect animals than by abusing cats and encouraging the ugly practice of exotic pets. There has to be a better way to promote vegetarianism than by making it seem unappetizing. There has to be a way of making art about activism and engagement less devoid of interaction and humanity. And there has to be an art of gesture and impulse with room for care and thought.

Sarah Frost ran at P.P.O.W. through May 14, 2011, Krzysztof Wodiczko at Galerie Lelong through March 19, Andrea Bowers at Andrew Kreps through December 17, and "Fracking: Art and Activism Against the Drill" at Exit Art through March 26. Liz Magic Laser ran at Derek Eller through April 21, 2012, Ruth Hardinger at Creon through April 19, Henry Taylor at MoMA PS1 through April 9, and Darren Bader there through May 14.