Portraits Made Uneasy

John Haberin New York City

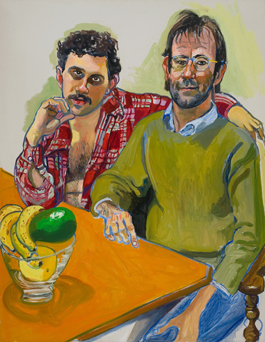

Alice Neel and Rick Barton

Alice Neel makes it look easy. That shock of hair, the restless edge of restless fingers, the changing colors of a solid sweater in the light—just throw them down in a brushstroke or two, thick or thin, and you have not just a portrait, but a fine one. It can communicate affection or unease. No wonder Neel set the style so much portraiture today.

The dark outlines of facial features may look more like bags under the sitter's eyes. Shadows on a table or the wall may look like a paint job that barely got going. Yet they are all that you need to define a personality, a room, or the light. She died in 1984, when painting and portraits were largely out of style. Yet one should never forget, a Met retrospective argues, that she fought for herself and for people every inch of the way.  For an alternative model for portraits, the Morgan finds the same unease sixty years ago in Rick Barton, but with little more than an unsparing pen.

For an alternative model for portraits, the Morgan finds the same unease sixty years ago in Rick Barton, but with little more than an unsparing pen.

Slow in coming

Neel hit her stride late in life, but artists have been watching ever since. With the revival of painting, her style seems to be everywhere. With a turn from postmodern irony to cultural diversity and self-assertion, her boldness seems just as relevant. Just this spring in the galleries, Jordan Casteel laid down her shadowed flesh tones and Jake McCord his bright, shaggy hair, and they could not have done it without her. It has become the closest the twenty-first century gets to a kind of academic art. Depart from it at your peril.

Does it hurt that her admirers tend to take it easy? Neel's sitters do, too, and she takes pride in them as well. In her late work, they seem to bask in perpetual sunlight, even indoors under studio lights. They are almost always seated, a privilege in portraiture for popes and presidents. They may sit alone or with the one they love. They get their choice of seat, too, and a chance to fling a leg over its arm or a hand over its back.

Once again, though, one has to overlook the unease in their stained flesh. They may look wary of the painter and of you. A mother and child cling together not just out of love, but also out of fear. One has to overlook, too, how long they were in coming. Neel was born in 1900, and she had to live through a century's darkest hours. The Met keeps returning to them at that, with an arrangement by theme as much as chronology. It sees from the start a political artist and a fighter.

This is not the Neel you know, but older, darker, and more engaged. In her politics and in her art, she recapitulates an American century. For a painter so associated with brightness, she began all but in the dark. She felt the influence of the Ash Can school and such urban realists as Robert Henri. Her very first portraits stick to smooth surfaces and muted colors much like his. If they are also portraits of New York, her history is inseparable from a multicultural city's as well. She moved often and kept her studio wherever she lived.

She did not find herself at home right away, no more than with her style. She reached the Greenwich Village scene by way of Havana and the Bronx. She had later studios in East Harlem and a largely black extension of the Upper West Side. The neighborhoods had a nervous energy, but also their darkness. She paints a fish market with huge windows reaching for the sky, but the shoppers seem barely able to move or to breathe. She paints poverty in the Great Depression and a protest against the Nazi killing of Jews, with Communist banners a demonic red against the night.

Works like these have a crowded but lethargic center of action, like New York for George Bellows. They also take on the terror of German Expressionism, with skulls for faces. They are committed to plain truths. Neel paints psychiatric hospitals and a suicide ward, but a clinic for babies looks no more promising in its emergent life. An intersection buries hopes under crossing streets and heavy snow, while Central Park offers steep stairs and the face of a hill.

The political and the personal

Neel took up portraiture to give people their voices, and the Met calls the show "People Come First." If they are also friends and lovers, the personal was the political for her long ago. After marriage to a Cuban artist, she had a child by a Puerto Rican musician, before a subsequent lover set many of her paintings on fire and slashed right through the rest. Her private life after that is her business, apart from a self-portrait, grandmotherly but with a brush in her hand, and a portrait of her troubled older son. Still, it is hard to separate causes from friends. A room for "counter / culture" shows not a bohemian lifestyle, but James Farmer, the civil-rights leader, and she worked for a radical magazine, New Masses.

Sexuality here is a political matter as well. She had drawn her husband on his back, crotch forward, like an infamous woman for Gustave Courbet half a century before. In her mature work, double portraits almost always show same-sex couples. An exception, Benny Andrews, poses with his wife. Neel must have felt a kindred spirit in the African American portrait painter, but he is dozing off. But then it is never easy to know when Neel chose their poses to make them more unsettling—just as she plopped down a still life in front of Geoffrey Hendricks, the Fluxus artist.

Her changing place in the art of her time continues—but through others with mixed feelings about her realism. She paints Henry Geldzahler, the Met's curator and a champion of American Modernism from Mark Rothko to Frank Stella. She paints Robert Smithson miles from his earthworks and Gregory Battcock, who wrote on Minimalism. She paints Lucy Lippard, who brought women artists and conceptual art into the mainstream, and Andy Warhol naked from the waist up after an assassination attempt. Once again Neel cannot resist an ugly truth, and once again she cannot resist calling it beauty. With his usual wry innocence, Warhol compared his scars to high fashion.

How much did any of them influence her? Just to ask is also to ask when Neel found her high style, and there is no one answer. Instead of a breakthrough, she shows a gradual but inexorable brightening. It could be connected to Pop Art and the abstract art that she refused, but also to the New York that she loved. Each new studio had its own sunlight, and she passed later summers in New Jersey. I kept holding out for thicker brushwork and the light—only for the curators, Kelly Baum and Randall Griffey with Brinda Kumar, to double back to darker memories. And then, just as the lightness triumphs, she is entering her seventies with barely a decade to live.

By then, she had become a fixture, if a radical one. She met Jimmy Carter, appeared on the Tonight show, and designed a cover for Time featuring Kate Millett, the author of Sexual Politics. She still sought to tell the truth through the lives of others. It was not a theme new to art, and a revealing alcove pairs her with museum classics. Suzanne Valadon had her nude on a sofa, Mary Cassatt her mother and child, August Sander his portraits as types, Helen Levitt her boys out on the street, and Jacob Lawrence his Builders and American struggle. An awkward, anxious mother and child by Vincent van Gogh could almost be Neel's own.

Still, it is her legacy for today. It may also explain her frequent portraits of pregnant women: show the physical and psychological toll, and show its beauty. Again one can underestimate either half of the equation. At the show's entrance, a pregnant woman sits, face and belly forward, in front of her reflection in a full-length mirror, which lends her swollen body a sinuous artistry. I may not like Neel's familiar art much more than before, even as I kept dying by the end to see it, but it no longer looks easy.

Alone again

For just four years, from 1958 to 1962, Rick Barton allowed others into his private world. His pen adapts easily from the outline of a nude to crumpled linens on an unmade bed. Others let their guard down as well, like a man in Barcelona who treats a cathedral like a barstool set aside each evening for him. Objects have lives of their own, too, like the coffee cups and ashtrays that over his bedroom—or the gay desiring that spills out from drawings within drawings on the wall. And yet intimacy for Barton was hard to find, and his own history is little more than a blur. One can hardly call his return to New York a retrospective, not when so much remains unknown.

Barton grew up just blocks from the Morgan Library, where not everyone shared in J. P. Morgan's luxury. A self-proclaimed "dead-end kid," he joined the Navy in 1945, late enough that his war record is a cipher as well apart from service in China. Yet it got him looking beyond New York, and he relocated to San Francisco in the 1950s, just in time for his drawings to begin. What of the ten years after the Navy or the remaining thirty years of his life? Aside from a move to San Diego, no one knows. If art today makes a point of diversity and rediscovery, there is little more to discover—but what there is shows a restless eye and, if only briefly, unceasing pen.

Barton grew up just blocks from the Morgan Library, where not everyone shared in J. P. Morgan's luxury. A self-proclaimed "dead-end kid," he joined the Navy in 1945, late enough that his war record is a cipher as well apart from service in China. Yet it got him looking beyond New York, and he relocated to San Francisco in the 1950s, just in time for his drawings to begin. What of the ten years after the Navy or the remaining thirty years of his life? Aside from a move to San Diego, no one knows. If art today makes a point of diversity and rediscovery, there is little more to discover—but what there is shows a restless eye and, if only briefly, unceasing pen.

At the exhibition's center is a pair of sketchbooks, on two sides of the sole display case. That already presents an enigma. A sketchbook is so often a private affair, meant for the artist alone. Yet these are accordion books, a form of book art for presentation to others, from an artist who thought of himself as a writer. He was not drawing, he said, but "writing a chrysanthemum." And he shared his artist's books with Etel Adnan, a more serene spirit who had seen nothing like them.

I have seen my share of fold-out books before, but never on a scale of thirty pages. As one walks alongside, the images keep coming, especially male faces. They could be his circle of friends, an evolving self-portrait, or a single obsession. His pen keeps coming, too, like a single ever-twisting line. It reduces a nude to eyes, brows, nipples, thick lips, the width of a chin, and the turn of a butt. The Morgan sees a soul mate in early Andy Warhol, whom he could not have known, but something was in the air.

It also spots a parallel in Henri Matisse, a precursor to his botanic drawings. And those, too, have a fascination with outlines and a nervous energy. A vine spirals upward to the point that it crosses onto a second sheet. Barton also copied Japanese drawing and Albrecht Dürer, another obsessive draftsman. And yet, for all that he reveals, Barton can never overcome years of disguise and reserve. He adopts backward writing and rarely appears in his drawings apart from that unceasing line and, barely within the frame, the artist's hand.

If he holds back, so do others. Individuals rarely share a scene, except when they barely acknowledge each other. In jail for dealing drugs, he sketches fellow inmates, one looking through bars with the persistence of a surveillance camera. Back in his room, Barton lies in bed afraid to look past the covers. A second man looks out the window, his back to the observer, but he could equally well be preening at a bathroom vanity. As one title has it, Alone Again.

For all that and years of mental illness, he is not friendless. He found fellow Beat poets and strangers in and around North Beach, like a bagel shop, Foster's cafeteria, and a jazz club, The Black Cat. He enjoyed public spaces, like that cathedral in Barcelona and many more in Mexico City. He frequented a bookstore, whose owner, Henry Evans, founded Peregrine Press. Evans became his collaborator and supporter. Thanks to him, there survives a small window onto a short, perplexing career.

Alice Neel ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through August 1, 2021, Rick Barton at The Morgan Library through September 11, 2022.