Entrepreneur of the Fantastic

John Haberin New York City

Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe

For the Fourth of July weekend, an American theme. In 1985, chemists finally detected fullerenes, carbon molecules shaped like soccer balls. R. Buckminster Fuller would have taken more credit, but he had died two years before.

Fullerenes come in many forms, but even the simplest, dubbed buckminsterfullerene, contains sixty carbon atoms. They embody Fuller's ideal structure, the union of the tetrahedron and the sphere, and it gives them the stability that he valued and predicted. They do undergo chemical reactions, but they have as yet no obvious application. They occur naturally but sparingly in soot, and to this day no one knows for certain their toxicity. The discovers won a Nobel Prize in 1996. Fuller, or course, did not.

Buckyballs have come to stand for his vision, but they might also stand for ups and downs of a fertile but and troubled career. The Whitney calls its retrospective "Starting with the Universe," and like Fuller himself it challenges one to separate fact from fiction. He could play scientist, designer, architect, engineer, sociologist, environmentalist, or blusterer. Born in 1895, he could be far ahead of his time or off in his own world. On film, he appears as a cross between a college professor and a snake-oil salesman. The combination may make him—a descendant of Margaret Fuller, the American transcendentalist who coupled feminism with a belief in divine energy—a prototype for Modernism in America.

"Best of Friends," an exhibition not long ago at the Noguchi Garden Museum already surveyed Fuller's life and ideas, and I try not to repeat the same story. I invite you to consider this as the second part of a two-part overview.

Fuller brush man

At the Whitney one can hardly keep straight what came to exist, what lives on in the imagination, and what merely fell by the wayside. Fuller's structures, like prefabricated housing even now, might save humankind or force it into a mold. They could blend art and science or muddle the two. could span unprecedented distances—and, in the architect's mind, Einstein's four dimensions of spacetime—but the roof could leak.

By 1927, he envisioned 4D Lightful Towers with a complex, tapering geometry, and he promoted them for decades. (Promotion for Fuller always starts with a brand name—4D as spacetime, light as lightweight engineering structures, and lightful as filled with light, but also dee-lightful.) No one took him up on them (although they may have influenced a light-filled buckyball much later in Madison Square). Renamed the Dymaxion Houses, they morphed by the 1940s into smaller, bell-shaped dwellings on pedestals. He meant them as units for garden communities that never came to pass. He imagined them floating high above, indistinguishable from clouds.

He imagined them floating in the East River just off the United Nations, as just one more contribution to "never built New York," to remind the global community of sustainable architecture and the needs of spaceship Earth. He imagined his own map of the planet as a further reminder. He considered it an improvement on the Mercator projection, because it displayed the globe in two dimensions without breaking up the outline of the continents.

His housing promised laundry machines that accept clothes one at a time. They were to come out "washed, dried, and completely sterilized in three minutes." The formulas sounds as if it applies to the inhabitants, too. Yet the houses also have a human side, symbolized by their organic shape, like, huge jellyfish. By recycling existing grain sheds and airplane materials, they look ahead to environmentally friendly architecture today, such as the "container home kits" from the firm Lot-Ek.

Separate, free-standing Dymaxion bathrooms found no takers either, but then New York is still finding a place for public toilets. They have a spooky resemblance to self-contained Living Units today by Andrea Zittel and her "A-Z Administrative Services." Strangest of all, people are commissioning her work as homes. Fuller would have told her to adopt an efficient geometry. Another he inspired, Tomás Saraceno with his Cloud City, did just that.

Fuller's trademark spun out into the Dymaxion Car, a vehicle so unstable at high speeds that its front wheel lifted itself off the ground. Fuller's second prototype lowered its center of gravity, and its three wheels could turn on a dime. However, his mind had turned anyway to flight. As he boasts on film, ever the Fuller brush man, it was always "more than just a car." At the Whitney, the lobby gallery accentuates its sleek outlines, black surface, and sheer mass. It looks in fact, quite the gas guzzler.

The machine in the garden

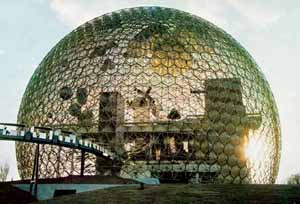

The goal of strong, lightweight architecture culminated in his geodesic domes. At last he captured serious clients and the popular imagination. Ford commissioned one in 1953, as a roof that could span eighty-three meters. He built another as his home in 1960, and others sprung up soon after. One served as the U.S. Pavilion at the 1967 Montreal Expo—among several for federal and military agencies. Other domes remained on the drawing board as clients withdrew.

Only two years before, the Noguchi Garden Museum gave Fuller a concise retrospective, on the theme of collaborations between him and Isamu Noguchi. The Whitney includes some of the same items, and it cannot compete with the sculptor's setting and artistry. The sole surviving Dymaxion Car looks dramatic, and Fuller's Air-Ocean World Map gives one room a colorful floor. I could appreciate my place on the planet. That still left drawings and memorabilia to pore over and chronologies to sort out. The largest and most vivid structure, a curtain of Octet Trusses by the elevators, like a recreation of Naum Gabo sculpture with humble wire hangers, amounts to a contemporary tribute to Fuller by other hands.

In a sense, though, the exhibitions complement each other. The first showed Fuller as an achiever, within a community of artists, starting at a tavern in Greenwich Village. One could see him as an artist and designer, his geodesic dome incorporated into Noguchi's elegant concert arena. At the Whitney, he does turn up in 1948 among the artists at Black Mountain College, where Robert Rauschenberg studied. He cavorts on stage with Elaine de Kooning and Merce Cunningham. It would be hard to say who looks most uncomfortable beside the other.

Both exhibitions show Fuller as a bundle of contradictions and as something of a street-corner prophet, one who might appeal to such younger visionaries as Hariri & Hariri today. However, the Whitney makes it easier to pin down the contradictions and the prophecy. His idealism, his connections between art and design, and early interest in mass-produced structures have obvious parallels with European Modernism—from the Russian revolution to the Bauhaus. The housing shares its setting and stilts with Le Corbusier's garden city, with the jellyfish swimming over from the Viennese school. In crossing the Atlantic, though, the map of the world has shifted. The architect of utopia has become the entrepreneur of the fantastic.

It appears in Fuller's knack for talking and for trademarks. In one account, an advertising man even helped him coin Dymaxion. It appears in his refusal to stand above his architecture, much as the towers quickly shrink to a couple of stories. He is placing human beings within the garden and the garden within the Earth. It appears in his term spaceship Earth, the humility of the concept belied by the magic of the word spaceship. He can save humanity by directing its attention to the Earth, save the Earth by turning it into a machine, and save the machine by propelling it into space.

Where Le Corbusier seeks perfection, Fuller's ghost in the machine demands efficiency. He has his head and housing in the clouds, and he can offer to instruct the United Nations, but to teach recycling. Like the image of the hustler, the lesson has its dark side. Early on, he imagines a zeppelin simultaneously delivering his 4D Towers and dropping bombs, like a vision of capitalism's "creative destruction." Stanley Kubrick might have turned it into a dark comedy. Is it an accident that he caught on in the 1960s, the summer of love and of Vietnam?

"Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe" ran through September 21, 2008, at The Whitney Museum of American Art. This review continues the story of "Best of Friends: Buckminster Fuller and Isamu Noguchi," at the Noguchi Garden Museum in 2006.