The Price of Justice

John Haberin New York City

Titus Kaphar and Reginald Dwayne Betts

Simone Leigh and Purvis Young

If you have ever wanted to scream that Titus Kaphar takes kids off the street and treats them as saints, go ahead. The artist is listening.

In fact, he and Reginald Dwayne Betts take it as an imperative. They also take it as a parable of the price that African Americans and others must pay for justice in the face of cash bail. Meanwhile Simone Leigh sees a black woman through two senses of confinement,  in childbirth and in prison. Earlier, Purvis Young as an outsider never left behind the urgency of the streets.

in childbirth and in prison. Earlier, Purvis Young as an outsider never left behind the urgency of the streets.

Criminals or saints?

Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, to name just two, have done justice to icons of American democracy, with the Obama state portraits. Kaphar looks to Byzantine icons for a sense of African American community. His recent portraits adopt their oval format and gold backgrounds, overlaid with a meticulous realism. Like saints but more literally, they are also larger than life. Each face reaches down well below your waist while looking you directly in the eye. Thick tar only adds to the confrontation while insisting on their blackness.

Are they right there, in your face, like street life for Alexander Brewington? Just as often, they are out of the public eye, in prison for months or years without trial, because they cannot afford bail, and the legal process is in no hurry to bring them before a jury. Wiley, whose portraits have their own dry shadows and decorative sheen, poses his young men like fashionistas—and they suffer from it. If Kaphar's remind you more of mug shots, that is not an accident. The height of the tar indicates the subject's time in detention. Now just two examples appear in a show devoted to their chances for release.

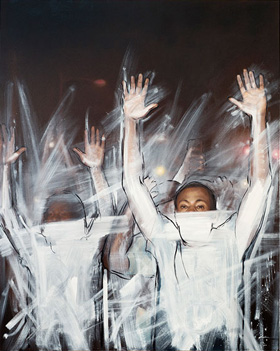

Kaphar, like Jamaal Peterman, has painted black males in prison before, as Yet Another Fight for Remembrance. There he veiled them in white, much as now he sets their ghostly presence apart with tar. There, too, they raised their arms in a cry for freedom, like a riot or an uprising in the hands of Purvis Young. Here their demand for freedom comes not just from their character as individuals, but even more in words. Thirty screen prints in black include further portraits, but also poems and legal briefs by the Civil Rights Corps on their behalf. They are collaborations with Betts, the poet of record and an attorney.

Betts has had many lives now, including time behind bars for theft, just as he has many roles in the exhibition. Kaphar gives the black portraits a greater urgency through fine incised curves, like whiskers but more penetrating. Betts, in turn, defaces the legal documents by blackening much of their text. He mimes the act of censorship. Yet he thinks of the results as additional poetry. Together, the artists are finding a visual equivalent to lost lives while giving those lives a voice.

They appear amid a flurry of exhibitions on the themes of the displaced and the oppressed. Just down the hall, Julie Becker insists on them, while Edgar Heap of Birds asks whether his people chose to walk where they did and questions the promise of Lady Liberty. He could be speaking for those in prison, and his "broad stripes" (paired with "bright stars") could refer to the marks of censorship, but no. More than a century after Jules Tavernier, he is finding words for the Trail of Tears of Native Americans, which he then turns into street signs and monoprints. Street signs have a common purpose as warnings, while the monoprints have bright red or blue backgrounds and a slashing handwriting. He has an ear for poetry as well, like the "nuance of sky blue over you."

Still, he ends up sounding like everyone's least favorite civics teacher. So can Nancy Spero when it comes to women, also at MoMA PS1, and the Karrabing Film Collective, which records the indigenous people of Australia and its Northern Territories. Kaphar and Betts, too, preach to the choir, but they speak of far more than victimization. After all the redactions, their text rings out with the language of brute fact and of the Fourth Amendment. Anger alone seems complacent by comparison. The show may be newly timely or a bit late, now that New York and other states are undertaking bail reform, but it presents prisoners and those working for them as more than just icons.

In confinement

"Everything that's alive moves. If it didn't, it would be stagnant, dead." For the followers of John Africa, the line underlay MOVE's title, its hopes for black liberation, and its very nature as a movement. Now Simone Leigh places the group at the heart of "Loophole of Retreat," her Hugo Boss Prize installation at the Guggenheim. Yet nothing here moves, and MOVE, founded in 1972 in West Philadelphia, is long since dead. As so often for Leigh, what might begin in anger and agitprop ends in poignancy, and audio at the back of a tower gallery can barely break the silence.

Three large sculptures stand well apart, accentuating the stillness. A hut of raffia, the fabric of dried palm, speaks to African tradition, African family histories, and the African diaspora, and so may its chimney in the shape of a peace pipe but with twin bowls aimed in opposite directions. Yet the shelter, like her huts for a Harlem park in 2016, has no entrances or exits, and its pipe is not blowing smoke. Besides, its odd shape may suggest surveillance cameras, and she calls the work Panoptica—after the all-seeing eye of the police state for Michel Foucault and, before him, Jeremy Bentham. A woman's bronze head stands as a Sentinel but with blind eyes, like Leigh's heads in Chelsea not long before. Another has lost its arms as well, as Jug.

Three large sculptures stand well apart, accentuating the stillness. A hut of raffia, the fabric of dried palm, speaks to African tradition, African family histories, and the African diaspora, and so may its chimney in the shape of a peace pipe but with twin bowls aimed in opposite directions. Yet the shelter, like her huts for a Harlem park in 2016, has no entrances or exits, and its pipe is not blowing smoke. Besides, its odd shape may suggest surveillance cameras, and she calls the work Panoptica—after the all-seeing eye of the police state for Michel Foucault and, before him, Jeremy Bentham. A woman's bronze head stands as a Sentinel but with blind eyes, like Leigh's heads in Chelsea not long before. Another has lost its arms as well, as Jug.

Of course, they are women, and the hut's billow or the jug's bowl echo a skirt. Leigh associates women with the labor of caring and protection, and the sentinel wears more raffia as an apron. She also stands atop a corrugated cylinder and the shape of a shipping crate, but water cannot flow in this main, and the crate is going nowhere fast. One last bronze token has three knotted seams like leather, braided hair, or disfigured flesh. It also rests on a pedestal behind a trellised concrete wall. That is also where the voices begin.

One can barely make them out until a woman's gentle "I love you." The confusion captures actual protests this winter outside a prison in Sunset Park, in Brooklyn, which endured a week without electricity or heat. The single voice stands in for a MOVE member who gave birth in prison in 1978. Other prisoners distracted the guards long enough for her to have her last close moments with her son until her release after more than thirty years. For Leigh, black radical women are not just artists as at the Brooklyn Museum in 2017. They are mothers and activists, and they may also have lost their voice.

The show's title quotes Harriet Jacobs, an abolitionist who escaped slavery by hiding under her grandmother's rafters for seven years. The museum speaks of her "astonishing fortitude that carved out a space of sanctuary and autonomy," but it was also the space of confinement—at a time when confinement still meant childbirth as well. The law for Jacobs in 1861 did not offer much of a loophole. The museum speaks, too, of "the agency of black women and their power to inhabit worlds of their own creation," but these are small worlds. For all that, Leigh's work is not altogether stagnant. It derives its very impact from overflowing its comforts.

Leigh has a softness for easy answers. Wall text points out that the police bombed MOVE out of existence in 1985, destroying eleven lives and an entire neighborhood. It does not note that the movement packed guns and the mother was in jail for murder, although it may have surrendered its guns, and she well may have been framed. A larger African American bust, this time a girl, looks down on Tenth Avenue this summer from the High Line, her back to the wealth of Hudson Yards. She lets you know just who deserves a place there and who does not (so there). Still, Leigh has a gift for tender and harsh realities—and a moving history.

A riot going on

A single black scrawl hovers over painting after painting, Young. It may cover the side of a building or a truck—and indeed the artist hung his work on the outside of abandoned buildings, as an uneasy compromise between an exhibition and graffiti. It may float just out of reach of the black actors below. They and the letters are of a piece in their fluid cursive, and both seem to embody the madness of youth under pressure. There is a riot going on, and both the rioters and the city will suffer. But then they have suffered enough already.

In reality, it is only the artist's signature, but you knew that. It just refuses to settle neatly into the lower edge of a painting—much like anything else by Purvis Young. His African Americans have been reduced almost to stick figures, but that does not keep them from gesturing hopefully or wildly. They might be reaching for freedom, for help, for one another, or for the sky. They and everything around them are in motion, like the trucks, boats, and even buildings. Slits in the apartment blocks for windows carry on the stubborn weave and the blackness.

A painting itself will not sit still. Young worked on found wood, in black and an often fiery red, and he affixed thicker pieces to the edges, like a frame. Then he painted on those, too, in daubs, swirls, and cryptic images. Sometimes they show faces, like insets in a larger picture. They might spell out the humanity of those caught up in events only partly of their own making. They matter, and they are matter in motion.

Young, who died in 2010, often comes labeled as outsider art, to the extent that he gets noticed at all. And no question that he kept his distance from New York. Born in 1943, this artist had national aspirations, but only in evoking events and the inner city, like Overtown in Miami, where he lived and worked. Still, he prefers felt action to the obsessive detail of much outsider art, not unlike Archibald Motley in a black community in Chicago. His scrappy assemblage accords with that of other African Americans as well, like Thornton Dial or Lonnie Holley. It has earned him a two-gallery exhibition on the Lower East Side.

All that motion makes Young hard to pin down. I think of the men as rioting, but mostly because he worked in the shadow of riots in Miami and Detroit. I think of them as men, but only because of their excess of testosterone—or because the faces are always male. I think of them as black because they are literally black, but then the larger faces are of every color, including yellow and red. Sometimes the faces are themselves the central subjects, and are they really the same cast in close-up? They could be ever so proper adults, commenting sanely or officiously on the action.

Other allusions fly past just as quickly. The boats could carry slaves from Africa or boat people from Vietnam, and some figures appear in chains or halos. Every so often the assemblage throws in plastic or receipts, but receipts of what? Young can be clumsy and infuriating, but then so for him was life. For twenty-five years, in work here through the mid-1990s, little seems to change, but then so, too, was the pace of change in America. He still captured the motion and the energy.

Titus Kaphar and Reginald Dwayne Betts ran at MoMA PS1 through May 5, 2019, Edgar Heap of Birds through September 8, and the Karrabing Film Collective through May 27. Simone Leigh ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through October 17, Purvis Young at Salon 94 Freeman through March 23 and at James Fuentes through March 24. This review of Young appeared in a slightly different form in Artillery magazine. Related reviews look at Titus Kaphar in 2015 and at Simone Leigh in 2018 and in Marcus Garvey Park.