Who Speaks for the Past?

John Haberin New York City

Titus Kaphar, Keris Salmon, and Kehinde Wiley

Who owns history? The question takes on special urgency in black America.

For Titus Kaphar, the question plays out against protests, prisons, police conduct, and art history. For Keris Salmon, it demands turning old texts and the American South into living history. Both are able to put a history in terms of family, and no doubt every family has its rituals. For some it will be church on Sunday, for others an afternoon indulgence in fashion magazines. For me, it might be catching up with art. And then there is Kehinde Wiley, for whom art is both fashion and religion.

Escaping prison

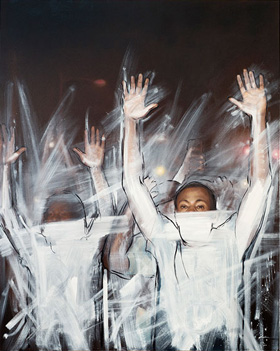

Sometimes events can overtake a work of art. The public squares of the world overflow with sculpture whose heroics speak only to the past. And sometimes events can take a while to catch up to art, lending it a greater meaning for the present. Titus Kaphar has focused on black males in prison, with paintings that can quickly take on a numbing sameness. So do blacks in the eyes of the police and "prison-industrial complex," but Kaphar must bear some of the blame, too. And then one sees men with their hands raised and their bodies veiled in white, on the point of invisibility or a living corpse—and after all the shameful, pointless, and repeated deaths, they have the immediacy of the headlines.

Events can move fast, and so can a career in art, but at least the pressure on dealers and emerging artists is a far lesser shame. Shows at three locations amount to that much abused institution, a midcareer retrospective, but the work dates back just three years, to 2011. The Studio Museum in Harlem has "The Jerome Project," an ongoing series based on mug shots and effaced with tar. Meanwhile Kaphar's Chelsea gallery has new paintings in its main branch, based on paintings from the Colonial era. There whites must give way, so that black lives matter and black eyes can see. That leaves the gallery's second space, where Kaphar gives "The Jerome Project" more of both a history and an impact.

Jerome, in case you were asking, is his father and then some. Trying to recover a personal connection through prison records, he found dozens recently arrested and bearing the very same name. Either the man has a more common last name than the artist, the police stop an unbelievable number of black men, or alas both. Kaphar renders their faces in an altogether conventional realism but against gold leaf, like Byzantine saints. Then he obliterates a portion of each in thick tar, from the mouth to the eyes or even beyond. Initially he calculated that portion from how much of their lives they had spent in prison—but they will all feel prison's mark on their existence for a long time to come, and soon enough Kaphar extended the mark of tar as well.

Breaking with his formula aside, Kaphar has a weakness for cheerleading and literalism, like Kerry James Marshall or Sable Elyse Smith at times and far too much political art. The Byzantine icons, for him, recall Jerome, the patron saint of librarians and scholars, and the meaning of tarring goes without saying. When it comes to white washing, though, he is not just whitewashing. The veils cover hands alone or group scenes. They convey a sense of motion, as if caught in the act of protest or dying. They convey art as a process, too, with Kaphar rubbing at his own work with turpentine and towels.

The formulas return for the new paintings, but with here and there a point of release. Literalism appears in the style of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, much as for David Shrobe, although Kaphar has a clear excuse in America's original sin of slavery. Canvas of George Washington himself gets peeled back, while others are shrouded in studio rags or entirely cut away. A black face peeks out anxiously from one gap, as if uncertain of his freedom, while another substitutes for Jesus on the cross. One can almost forgive the piety and Romanticism as a heritage of the originals, even if you and I have forgotten them. Besides, a cutout portrait draped over a waste bin approaches humor.

The real thrill, though, comes in the more unstable renderings along with the white washes. They include ghostlier takes on mug shots, holding the identifying letter board. They also include portraits in black on black, with disturbances that multiply features. Here, as also with Adam Pendleton, black identity seems to be slipping away before one's eyes. Who knows what will happen when, once again, Kaphar engages with the present. After the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Eric Garner in New York, and Trayvon Martin in Florida, the prison-industrial complex could seem almost a relief.

Plantation and family

So who owns history? Part of the historian's task is asking, while bearing in mind that anyone who claims to own history is lying. With Keris Salmon, it has also become the task of the artist in black America. Don't Knock at the Door, Little Child presents a Tennessee tobacco plantation as if out of the pages of a book. And then the voices begin to multiply, until they become a living history. All in their way speak for the past.

Naturally whites grapple with family history as well. Born in New York but raised in London, Dylan Stone attests to cultural divisions of his own while sharing a gallery with Salmon. He assembles a life-size watercolor of his parents' books, LPs, and video cassettes, in crisp colors that put my books and records to shame—the dated media attesting to their place in the past. Barbara and David Stone produced ever so serious films, and David tried to grapple with his son's chosen career by sending him clippings about art from ever so serious publications. The artist captures those clippings in file folders on the floor, laid out like cinder blocks for Carl Andre, and in a handwritten index rendered in additional watercolors. Like his father, he, too, reaches out by asserting control, as his own way of speaking for the past.

Salmon can bring more to a family conflict, though, for she describes an America still divided by Southern history. The division goes back to the framers, as defenders of liberty and as slaveholders. Wessyngton Plantation takes its name from a variant of Washington, and Salmon adds her photographs to text from The Washingtons of Wessyngton, a 2009 title by John Baker. And obviously the division became a chasm in the runup to civil war—or in the politics of red states versus blue states, old south and new, white and black today. One can see it in culture as well, from passionate Civil War art up north to the viciously white perspective of a movie as beloved as Gone with the Wind—a focus for Ina Archer as well. Kara Walker has made searing imagery out of that perspective, most recently at the Domino Sugar Refining Plant in Brooklyn.

Salmon's Confederacy is surely not a noble cause, but it is a home to faces unseen. Her photos practically insist on their silence, while the text keeps talking. Baker is a historian concerned for the details of everyday life, but his tone can shift within a sentence from a potboiler to precision. "As he attempted to grab her there was an extremely loud burst of thunder followed by lightning, which hit a tree near the overseer. – He then ran away and never attempted to bother her again." Indeed.

Salmon's continuing project takes on the same shifting messages. Her line breaks set GRAB HER and THUNDER in full caps standing alone, for an elegant but raunchy artist's book. Her six photos, in contrast, are modest in appearance as well as in number. She sticks to exteriors, in drab compositions that speak to distance and to exclusions. She then works with a skilled printer, in a font based on slave auction and runaway posters. The pages also belong to her history and to that of the Great Migration and the flight from the American South.

Salmon, a native New Yorker, first heard about the plantation from her white partner, who descends from its owners. She encountered it in person in a Tennessee museum after the publication of Baker's book. Her work's title, however, quotes Georgia Douglas Johnson, a poet of the Harlem Renaissance. Josie Roland Hodson, a sophomore at Stanford, serves as guest curator—and Salmon's daughter, who has never set foot in the South, contributes the gallery's statement. A lot of voices here are speaking. They will just have to wait for the next election to see who currently owns history.

Skin deep

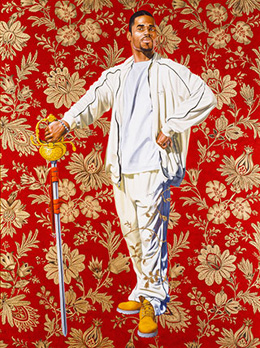

Kehinde Wiley leans on art to promote a shallow notion of black pride, but neither art nor blackness gains in the process. The first becomes a slick product for a market that has little interest in either racial equality or painterly difference. It looks to art history not for passion, challenge, or insight, but for the aura of a work of art.  And the second becomes a grand universal, transcending individuals and nations. It takes for granted the very reality of race, beyond prejudice and politics. At the Brooklyn Museum, it does little more than confuse glamour with identity.

And the second becomes a grand universal, transcending individuals and nations. It takes for granted the very reality of race, beyond prejudice and politics. At the Brooklyn Museum, it does little more than confuse glamour with identity.

For Wiley, race is decidedly skin deep, although he later shows far more promise with the Obama state portraits. Even in person, his paintings look like magazine spreads, and they have served as such in print. They pose anonymous black men and women like models, against flat, bright, decorative patterns like the floral display to accompany skin-care products. Skin tones shine in the bright lights of a runway—and in an insipid, formulaic realism. Clothing shines, too, with particular attention to product logos. In a bronze portrait bust, a young man balances a brand-name sneaker on his head.

He does so, the museum explains, to call attention to the exploitative conditions of its manufacture in Africa, but do not be taken in. Nothing matters more to Wiley than sports, fashion, and sex. Oh, and did I mention art and religion? Early on, the artist drew his poses from western religious art, including gilded icons and stained glass, although he allowed his sitters to choose their weapon. In time, he broadened his appropriations to include academic portrait sculpture kowtowing to the worst excesses of aristocracy, as well as contemporary prints meant as propaganda. He has scoured centuries of art in search of schlock—and then done everything he can to make it schlockier still.

Wall labels help identify the sources, but not consistently. They are way more concerned with quoting authorities to dignify Wiley still further. This is, after all, the art-world ritual of the midcareer retrospective, for an artist born in 1977, anointing another star. Jeffrey Deitch weighs in, on a well-meaning early portrait of a black man in a suit, set against a drab background preceding the gilding and the flowers, but then the dealer and former museum director should know something about marketing and self-promotion. So, too, does Wiley, who typifies the awkward combination of accessibility and pretence that appeals to high-end galleries, shallow collectors, and purported art advisors. Amid the models encountered on the streets, standing and on horseback, he throws in Michael Jackson.

He has had savvy and respectable backers as well, as in his year as artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and he sincerely wants to recover ordinary people as role models, a search that he calls "street casting." He reflects concern for blackness in European painting and popular culture, much like Barkley L. Hendricks and Mickalene Thomas—and he has recently added women, though not a gay black male, in response to complaints that his obsession with the black male amounts to too much testosterone. He even manages a "serious" source now and again, such as Hans Memling in Memling's portraits, Franz Hals, or Jacques-Louis David. Yet they all feed into a relentlessly upbeat message. Even when a woman poses as Judith beheading Holofernes, she has not the savage femininity of Artemisia Gentileschi, but only sweetness and light.

The curator, Eugenie Tsai, argues that Wiley pierces centuries of white privilege by taking to the streets, if not as lovingly as Alexander Brewington, much as Charles McGill pierces it with gold bags—but again do not believe it for an instant. He travels the globe for sitters, but with hardly a trace of local politics, personalities, or cultures. When Kaphar makes icons from mug shots, he puts in tension family crimes and black victimization. When Wiley copies a mug shot, the label explains, he sees "not a criminal, but a cherub." And where Memling pioneered portraiture as a defiantly secular image, Wiley places even his work after Memling in large frames to reaffirm the aura. God save art from its angels.

Titus Kaphar ran at the Studio Museum in Harlem through March 8, 2015, and at Jack Shainman through February 21, Keris Salmon at Josée Bienvenu through February 14, and Kehinde Wiley at the Brooklyn Museum through May 24. Dylan Stone ran at Bienvenu through December 20, 2014. A Related reviews pick up Kehinde Wiley in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Wiley's public sculpture and black Napoleon, and Titus Kaphar at MoMA PS1.