Make It Official

John Haberin New York City

Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald: The Obama Portraits

Troy Michie and Firelei Báez

For the first time in my life, I miss a former president. For the first time, too, I miss the National Portrait Gallery. Shall I credit both to Barack and Michelle Obama? No doubt, but Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald contribute, too, by treating them to flora and fancy dress, in their state portraits. They also speak to politics and the presidency. Three years later, they speak to New Yorkers as well, in a national tour with a stop at the Brooklyn Museum.

What makes an official portrait official? Is it all about varnishing over the truth? Not this time. Say what you will about politics, but the last president and first lady sat for portraits that have people talking—and museum attendance climbing.  They made that possible, too, with more than just their choice of artists. Wiley and Sherald often fall for a kind of politically correct official art, but for once something more ambitious shows through.

They made that possible, too, with more than just their choice of artists. Wiley and Sherald often fall for a kind of politically correct official art, but for once something more ambitious shows through.

Conservatives want back the dignity of the Oval Office and American history. They overlook art's and history's way of seeing more than surfaces. For Troy Michie, political art is history, in which a zoot suit stands for black culture and race riots, while for Firelei Báez it is pure joy. For Anna Boghiguian it is a calling to account, while for Hiwa K it is puzzling as his nation's future. Which makes most sense? Political change takes all four, but for once joy wins out.

Flora and fancy dress

To be sure, Donald J. Trump would have me missing all forty-four of his predecessors, even those who led America into the Great Recession, the Gilded Age, Jim Crow, and civil war. Still, the very idea of an official portrait has an awkward place in art. It dates to a time long past Renaissance princes and their commissions. Then, too, photography has taken over much of its role, on magazine and album covers. If Marilyn Monroe or Patti Smith has anything like an official portrait, thank Richard Avedon and Robert Mapplethorpe. The Obama painters did not have me expecting a change at that.

Kehinde Wiley has become a celebrity artist by treating ordinary people as celebrities, although he has also painted stardom in Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys. His young black males strut their macho stuff in front of decorative backgrounds that make them stiffer, shallower, and shinier still. He models one on Napoleon crossing the Alps for Jacques-Louis David. And a less familiar name, Amy Sherald puts style first and foremost as well. Icy grays stand for black flesh, and sharp colors pop out from patterned clothes. Still, she leans to flat erect figures, as if afraid to disturb their dignity by a reminder of their thoughts and lives.

Again, not this time—although one can feel a manufactured hush descend in Brooklyn over a huge space for just two paintings. Wiley has dropped the military hardware and hanging fruit in favor of a canopy of leaves. Filling the picture plane, it propels Barak Obama forward to where his eyes and crossed arms engage the viewer. They make him recognizably the thoughtful ex-president one wants to remember. They also overlap now and then his stately chair and informal seated pose. That works well, too, for the man who called on America to lead from behind.

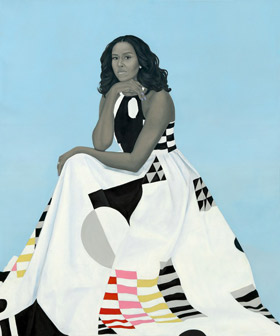

Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama does better yet as lawyer, teacher, activist, and fashion plate, in a portrait that John Singer Sargent himself might admire. She, too, is seated—with one hand on her knee, an elbow resting on that hand, and the other hand beneath her chin. These, a mostly white dress, a pale blue background, and a refusal to smile keep her at a measured distance, even as her pyramid spreads in all directions. Sherald keeps everything quiet except for character and paint. Try to remember a past official portrait that mattered as much for the first lady as for the president. But then try to remember a single artist in the National Portrait Gallery since Gilbert Stuart.

If the pair marks a departure for both artists, give credit where credit is due. It helps that Wiley had to show up for the occasion rather than delegating the job to his factory, for the president would expect no less. Still, he and his wife must have pushed the envelope. He reportedly told Wiley that he had no interest in playing another Napoleon, and who knows what she told Sherald? Wiley is not going anywhere new, even at barely forty, but Sherald, now forty-five, has since taken a break for matters of personal and family health. The Obamas, too, can afford now to take a deep breath.

The portraits bring out their place in history, but also their humanity. The museum notes how Obama's flora has its origins in Kenya and Indonesia, only to become the state flower of Illinois, where he gained attention as a community organizer in Chicago. With his suit and open collar, a world leader becomes approachable. The first lady's dress, in turn, reflects generations of Gee's Bend quilting—and she poses in a photo beside its practitioners today. As for her hand on her chin, confident and thoughtful, Sherald adds, women everywhere "can relate," and so now can I.

Clothes make the man

They say clothes make the man—unless, that is, clothes unmake him. Both came to pass in the darkest hours of World War II, when some of LA's growing minority population dressed for the jazz age. White resentment then, fed by thoughts of others living to excess amid wartime austerity, led to the Zoot Suit Riots in 1943. History has largely forgotten, but not Troy Michie, who creates a chronicle of racism and high style. It also cuts across past and present, to the demands of Black Lives Matter. American servicemen led the assault then, just as another point of reference for "the man" has now.

But really, the Zoot Suit Riots? Their invocation sounds like conceptual art, but they were all too real. They also brought a swift response. Eleanor Roosevelt wrote of the need to address race in America, and Earl Warren, then governor of California and later the chief justice who presided over Brown v. Board of Education, appointed a commission. The contrast with today underscores the persistence of prejudice. For Michie, it is also a matter of art and style.

His large collage has the bright fragmentation of Stuart Davis and American Cubism, already a stepping back to the jazz age. (The Whitney has called another black artist, Archibald Motley, "Jazz Age Modernist.") Smaller work becomes muter, thanks to button-down clothing and tailor's specs.  Both incorporate photographs of black men and women that could belong to then or now. Michie often excises black faces, miming acts of enforced anonymity and violence. Chain-link fences divide the gallery, along with bundled newspapers and an empty suit, and more fencing lies on the floor, rolled up around what could be forensic evidence.

Both incorporate photographs of black men and women that could belong to then or now. Michie often excises black faces, miming acts of enforced anonymity and violence. Chain-link fences divide the gallery, along with bundled newspapers and an empty suit, and more fencing lies on the floor, rolled up around what could be forensic evidence.

They could be deeply evocative or merely confusing, especially for those like me who had to turn to the Web for a point of reference. They also shift the focus awkwardly from Chicanos and LA to blackness and Harlem. Still, the fences succeed in bringing in racial barriers and barriers to immigration. Fat Cat Came to Play, runs a title, and a quote Malcolm X is double-edged. It describes the zoot suit as a "killer-diller coat" with "shoulders padded like a lunatic's cell." Even killers need protection.

Implicit, too, is another barrier, in gender. Shows of fashion designers often revolve around women, no (and never mind Virgil Abloh with Louis Vuitton)? Talk of "the black male" may seem provocative, as in a legendary show curated by Thelma Golden at the Whitney—or merely dated, as with the Whitney's "Incomplete History of Protest." It takes on more currency, though, for the LGBTQ communities, and Michie also appears in "Trigger" on that theme at the New Museum. That show's account of gender as "a tool and a weapon" can seem slippery. As with Cubism, though, sometimes it pays not to keep one's head on straight.

Yet another identity issue extends to white males, like the ones that voted for Trump. Right next door to Michie, Alex Mackin Dolan evokes automation and a crude form of AI (compared, say, to that of Refik Anadol at MoMA) as "Particle Accelerator of Angels." His constructions could pass for slot machines or juke boxes, but with a mechanical humanoid slumping listlessly forward. It might have replaced workers, or it might share their anxiety. It might have pushed any number of protruding buttons, illustrated with photos and schematic images, expecting another button to pop out. But then men, too, these days are expecting a lot.

The fire this time

Firelei Báez has a knack for making herself at home, even in the New York Public Library. Born in the Dominican Republic, she studied art in New York and divides her time between the city and Miami. Now she shares the library's Schomberg Center with Aspects of Negro Life, 1934 murals by Aaron Douglas. It is part of "inHarlem," a program of the Studio Museum dedicated to returning art to the community. In the words of the show's title, it is also "Joy Out of Fire." As a painting's title has it, she intends To Write Fire Until It Is in Every Breath.

Douglas incorporates documents and photos of black women, much as Nellie Mae Rowe incorporates herself. Báez builds on the women. Her unstretched canvas has the gentle haze and intense color of his tropical scenery while telling a story about black lives. They appear as fiery shapes in purple and red, as portraits in thought and action, and in a dance that even the 1930s would have understood. Still, she has enough detachment to depict a black face, perhaps her own, as Firewood Pretending to Be Fire. Sometimes, like James Baldwin, one may just have to settle for "the fire next time."

Anna Boghiguian is more concerned for teaching others a lesson, in the south extension of the New Museum. It about not her native Cairo but colonialism, the slave trade, and their aftermath in present-day America. It starts with the Portuguese spice trade and competition from the Dutch and England. And she scrawls it at length on the walls, much like a blackboard lesson. Then she illustrates it with a makeshift cotton field, cutout anti-immigration protests, white guys in business suits, African monkeys standing for you know who, and fried brains. A sail descending across the back adds a map of Africa and national flags to a sea of blue.

As an Iraqi Kurd, Hiwa K across the hall can offer only a lesson in futility. His videos include a boy hammering away at a chunk of marble, a shed waiting for people or rain, and a cauldron of fire. The pot's forged steel stands empty and ominous beside it. A man bloodied by quite possibly the loss of a leg gives way to a strolling guitarist. And what exactly is the artist balancing on his nose, and why? One can only hope that, like the eel on the end of Father William's nose for Lewis Carroll, it has made him so awfully clever.

Both have the obvious in mind, while drawing back from the obvious as artists. Boghiguian's cutouts keep visitors from the very wall text she wants them to read. And how does she get from the slave trade to racism today? Any American should be able to supply an answer, but she has trouble articulating one. Did art not at that long ago lose itself in critical theory and irony? These days, political art could use some.

It shows in the unalloyed pride of African American portraits by Titus Kaphar and Mickalene Thomas. It shows even with Obama. Still, there is no avoiding the demands to be heard—including the demands of black radical women and Latin American women. Báez takes a documentary tone in the public space of a research library. She found herself poring through archives at the Schomberg Center. This once, joy emerges from diligence and fire.

The National Portrait Gallery unveiled the Obama portraits on February 12, 2018; they came to The Brooklyn Museum in late August 2021, running through October 24, while Wiley's portrait after David hung in the lobby. Troy Michie ran at Company through January 21, 2018, Alex Mackin Dolan at David Lewis through December 22, 2017. Firelei Báez ran at the Schomberg Center of the New York Public Library in conjunction with the Studio Museum in Harlem through November 24, 2018, Anna Boghiguian and Hiwa K at the New Museum through August 19.